Scientists Say These Weather Machines Don't Work—So Why Do Farmers Keep Using Them?

A hail cannon is not a cannon that shoots hail. It does not belong to Ming the Merciless, nor was it ever offered as a plaything alongside a vibrator in some bizarre intergalactic leisure catalog. The idea that one might use either device for the same purpose is an amusing proposition, though entirely speculative. There is, however, a parody of Flash Gordon that exists, *Flesh Gordon*, which reportedly circulated through certain schools with remarkable speed and enthusiasm, whispered about in locker-lined hallways like a forbidden artifact of adolescent curiosity. The hail cannon, despite its dramatic name, has nothing to do with launching frozen precipitation. It does not create hailstones. In fact, creating hail would be counterproductive, like installing a sprinkler system that only activates during a hurricane. What it allegedly does is stop hailstones from forming. It is described as a shockwave generator, purportedly disrupting the formation of hail within storm clouds, though whether it disrupts anything beyond the peace and quiet of nearby residents remains an open question.

The mechanism involves producing a loud, explosive sound, essentially a massive “boomph”, that sends a pressure wave skyward, theoretically interfering with the growth of ice particles in developing storms. The visual design resembles a large cone mounted atop a box, a contraption that looks as if it were designed by someone who once saw a diagram of a combustion engine and decided to scale it up, tilt it skyward, and declare it finished. Inside the box, acetylene and oxygen are combined and ignited, creating a contained explosion whose force is directed upward through a narrow neck and into the cone, where it expands into a focused shock wave. The physics of this process, as described in manufacturer literature with the confidence of a magician explaining how they really do pull rabbits from hats, involves a precise choreography of combustion and expansion that would make a Swiss watchmaker weep with envy, if Swiss watchmakers cared about sky-bound explosions, which they don't, because they're sensible people. The mixture of acetylene and oxygen, highly flammable gases stored in separate tanks to prevent accidental detonation (a precaution that suggests even the manufacturers have some awareness of basic safety) is metered into the lower chamber where ignition occurs with the delicacy of a toddler striking a match. As the resulting blast passes through the constriction of the neck and into the widening cone, it transforms from a simple explosion into what manufacturers generously call a "focused atmospheric pulse", a phrase that sounds impressive until you realize it's essentially saying "we make loud noises and hope for the best."

One manufacturer, Mike Eggers Ltd of Nelson, New Zealand, claims their device creates this pulse with an effective radius of approximately 500 meters (1,600 feet), a figure that appears suspiciously precise given that atmospheric conditions are about as predictable as a cat in a room full of rocking chairs. The rhythmic firing pattern, every one to ten seconds during storm approach, is critical to the alleged mechanism, supposedly creating overlapping shock fronts that disrupt hailstone formation at multiple developmental stages, though it's equally effective at disrupting the sleep patterns of anyone within earshot. Neighbors of hail cannon operators experience this as relentless auditory assault; a 2008 Fox News report detailed Vermont orchardists waking "the entire valley" with their cannon's incessant booms, prompting formal complaints from residents who described the sound as "like living inside a bass drum being played by an enthusiastic but rhythmically challenged elephant." The conflict between farmers protecting their livelihoods and neighbors seeking peace highlights how pseudoscientific solutions can create real-world social friction, even as they fail to deliver on their meteorological promises, a situation not unlike installing a disco ball in your living room and claiming it improves your Wi-Fi signal.This has led some to liken it to an airzooka, a giant version of those toy vortex cannons that shoot rings of air, but scaled up to atmospheric intervention levels, and with significantly more paperwork required by local noise ordinances.

There is skepticism about whether this actually works. While many hail cannons have been installed in agricultural regions, particularly vineyards and orchards prone to storm damage, places where a single hailstorm can shred a year’s worth of labor in minutes, there is little scientific validation. The results of studies on their effectiveness are not merely inconclusive, they are, in fact, quite clear: the devices do not work. A 2006 review by meteorologists Jon Wieringa and Iwan Holleman in *Meteorologische Zeitschrift* examined decades of anecdotal claims, field reports, and attempted measurements, only to conclude that “the use of cannons or explosive rockets is a waste of money and effort.” Despite decades of use and numerous anecdotal claims, farmers swearing by them, neighbors swearing at them, no peer-reviewed research supports the idea that shockwaves can prevent hail formation. Just because it doesn’t hail after firing the cannon doesn’t mean it would have hailed in the first place. Weather systems are complex, and correlation does not imply causation. The absence of hail could simply reflect natural variability, or the fact that storms often miss their targets by a few kilometers, a margin that makes all the difference when your livelihood hangs on the weather.

Another reason to doubt the efficacy of hail cannons lies in the environment in which they operate. Hailstorms are accompanied by phenomena far more powerful than any man-made boom. Thunderbolts and lightning, for instance, produce shockwaves orders of magnitude stronger than those from a hail cannon. If such intense natural forces cannot reliably disrupt hail formation, indeed, if they often precede or accompany the very hail one is trying to prevent, it seems unlikely that a ground-based explosion, repeating every ten seconds like a malfunctioning foghorn, would succeed. The notion that a localized blast could alter cloud dynamics on a scale sufficient to stop hail is, at best, optimistic. It raises the question of whether people are simply firing explosive gases into the air for no discernible reason, which, while perhaps entertaining, lacks scientific merit. Charles Knight, a cloud physicist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, put it bluntly in a 2008 newspaper article: “I don’t find anyone in the scientific community who would validate hail cannons, but there are believers in all sorts of things. It would be very hard to prove they don’t work, weather being as unpredictable as it is.” And therein lies the loophole: uncertainty is fertile ground for hope, and hope, in the face of ruined crops and ruined harvests, is not easily dismissed.

This leads to a related but even more unusual device: the cloudbuster. The name may ring a bell because Kate Bush released a song titled *Cloudbusting* in 1985, a haunting, orchestral ballad that captures both the tenderness and tragedy of a son’s love for his father. The song was inspired by the real-life invention and its creator, Wilhelm Reich, an Austrian psychoanalyst whose career began in the shadow of Freud and ended in the glare of federal prosecution. Reich was not a meteorologist, and his qualifications in weather manipulation were, to put it mildly, nonexistent. If the hail cannon at least pretends to operate within the realm of acoustics and pressure waves, the cloudbuster dispenses with pretense entirely. It consists of an array of parallel hollow copper tubes, mounted on a swiveling base, connected at the rear to flexible copper hoses that trail into buckets of water or nearby streams. The device was said to manipulate something called orgone energy.

Orgone energy, pronounced either “org-own” or “org-on,” though Wikipedia explicitly marks the pronunciation as uncertain, is a pseudoscientific concept with no basis in physics. It is described as a hypothetical universal life force, akin to chi, prana, or the Force from *Star Wars*, but with more paperwork and significantly more paranoia. According to Reich, orgone energy permeates all living things and the atmosphere, pulsing in blue waves visible only to the enlightened or the deluded. He believed it could be concentrated or drained using specific apparatuses, and that stagnant orgone led to emotional repression, cancer, and drought. By placing the cloudbuster’s hoses in water, something Reich believed to be a natural orgone absorber, and pointing the tubes skyward, practitioners believed they could draw orgone energy from the atmosphere, thereby influencing weather patterns, specifically, inducing rain. One might reasonably describe this as complete nonsense, and indeed, the label “pseudoscientific” is applied with seven citations in the relevant Wikipedia entry, as if to emphasize that the scientific community has thoroughly rejected the idea, and perhaps to warn future researchers not to waste their time.

The cloudbuster did not involve launching dogs named Buster into the sky, nor was it inspired by the 1988 film *Buster*, about the Great Train Robbery. It was a stationary apparatus, sitting in fields with tubes pointing upward, supposedly pulling invisible energy from the air like a cosmic vacuum cleaner. Reich conducted dozens of experiments with the device across the American countryside, calling the research “Cosmic orgone engineering,” a phrase that sounds like a rejected Marvel Comics subtitle. The remains of one of his original cloudbusters can still be found in Rangeley, Maine, rusting quietly at the Orgone Energy Observatory, now part of the Wilhelm Reich Museum, an eerie monument to ambition unmoored from empirical reality. The device also appears in Dušan Makavejev’s 1971 film *W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism*, a surreal blend of biography and political satire that treats Reich’s life as both tragedy and farce.

The idea that submerging hoses in water and aiming metal pipes at the sky could make it rain is, on its face, absurd. Yet someone once summarized it perfectly by saying that the inventor was essentially trying to make the Force cry by placing a vibraphone in water via some hoses. That description captures the theatrical, almost mystical nature of the device better than any technical explanation. Some modern believers have reinvented the cloudbuster under names like “chembuster” or “orgone cannon,” marketing them as countermeasures against chemtrails, a conspiracy theory alleging that aircraft contrails are actually chemical agents dispersed for secret government purposes. These newer versions are often packed with crystals and metal filings, decorated with mystical symbols, and marketed to those who see pollution not only in the air but woven into the very fabric of reality.

Outside of fringe science, there have been various attempts to influence weather using more conventional methods. One such method is cloud seeding, which involves dispersing substances like silver iodide or dry ice into clouds to encourage precipitation. Unlike the hail cannon or cloudbuster, cloud seeding has some grounding in atmospheric physics. The idea is that introducing tiny particles into supercooled water droplets can trigger the formation of ice crystals, which then grow and fall as snow or rain. This technique has been used in drought-prone areas, ski resorts seeking extra snowfall, and even in attempts to clear fog from airport runways. It is, at least, an attempt to work within the known laws of nature, rather than invent new ones.

The process typically involves aircraft or ground-based generators releasing the seeding material into the atmosphere. In mountainous regions, for example, silver iodide is burned in generators placed upwind of target areas, allowing the particles to be carried into clouds by prevailing winds. The results have been mixed. Some studies suggest modest increases in precipitation under specific conditions, while others show no measurable effect. The challenge lies in proving causation, knowing whether rain would have fallen anyway, or if the seeding actually made the difference. Because weather systems are inherently chaotic, isolating the impact of human intervention is extremely difficult. As one meteorologist put it, “It’s like trying to prove that one sneeze in a hurricane changed its path.”

Despite the uncertainty, cloud seeding continues to be used in various parts of the world. China, for instance, has invested heavily in large-scale weather modification programs, deploying thousands of rocket launchers and aircraft to seed clouds during dry seasons, with the stated goal of ensuring blue skies for major events and filling reservoirs during droughts. In the western United States, several states run seasonal cloud seeding projects in hopes of boosting snowpack in the Rockies, a critical water source for millions. Bringing an umbrella to a picnic and then taking credit for the sunshine is what this technology is like, at best, it’s a tool that might yield small gains under the right circumstances; it isn’t regarded as a solution to climate change or long-term water shortages

Still, the practice is not without controversy. Environmental concerns include the potential accumulation of silver iodide in soil and water, though current evidence suggests the levels used are too low to pose a significant risk. More abstract concerns involve the ethics of altering natural processes, especially when downstream communities might be affected. If one region seeds clouds to make rain, does that deprive another area of its share? The atmosphere does not respect political boundaries, and tampering with it, even slightly, raises questions about responsibility and unintended consequences. Legal disputes have arisen between neighboring states, and in some cases, farmers have sued cloud seeding operators, claiming their fields were left dry while others benefited.

Then there are the more whimsical attempts at weather control. In some cultures, rain dances and ritual ceremonies are performed to summon rain during droughts. While these are generally understood as cultural or spiritual practices rather than scientific interventions, they reflect the same deep-seated human desire to influence the skies. Similarly, in the early 20th century, a man named Charles Hatfield gained notoriety as a “rainmaker” by building towers that released a secret chemical mixture into the air, his formula, he claimed, was a blend of 23 ingredients, including acetone and sulfuric acid, though he never revealed the exact proportions. He claimed success after several heavy rains followed his treatments, though scientists dismissed his methods as coincidental. When a dam broke after one such event, leading to widespread flooding, he was nearly blamed, though he never accepted payment, citing a clause that required results to be “natural rainfall.”

The boundary between science and superstition in weather modification is often thin. Devices like the hail cannon persist because people want to believe they work. Farmers facing crop damage from storms are willing to try anything that offers hope, even if the mechanism defies physics. The loud bang of the cannon provides a psychological benefit, if nothing else, it feels like action is being taken. There’s comfort in doing something, even if that something has no measurable effect. This is part of why such technologies endure despite a lack of evidence. In France, where hail cannons are still used in wine-growing regions, some communities once rang church bells during storms, believing the sound would scare away hail, a tradition later replaced by firing rockets into the sky.

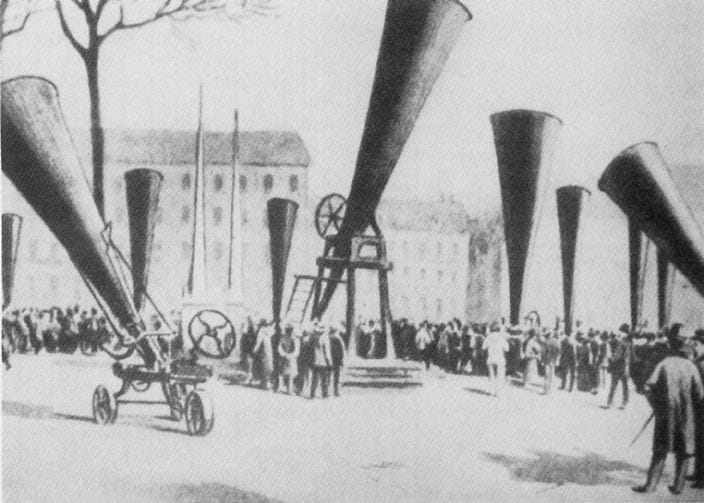

The transition from sacred to explosive was neither sudden nor particularly well-thought-out. As documented in a 1905 Southland Times article, French vignerons had long employed "the pealing of church bells" as their first line of defense against hail, a practice so widespread that it reportedly "caused much damage to the bells themselves" from overuse, presumably because nothing says "divine intervention" like a cracked church bell shaped like a question mark. By the early 20th century, this ecclesiastical approach gave way to more violent interventions, because as every rational person knows, if gentle ringing doesn't work, the solution must be to add explosives. A June 1909 Popular Mechanics article dryly noted that "cannons and rockets" had become "the accepted method of hail dispersal in European vineyards," though it cautiously added that "no scientific proof of their efficacy has been forthcoming", a diplomatic way of saying "this is complete nonsense, but the French wine industry has never let facts get in the way of a good story."

The shift reflected both technological optimism and desperation; winegrowers facing catastrophic losses were willing to embrace any solution that sounded suitably impressive, much like modern consumers who buy expensive bottled water because it has "mountain spring" written on the label in an elegant font. In Slovakia's Banská Štiavnica Old Castle, a particularly ornate hail cannon, likely designed by local engineer Julius Sokol around 1901, still stands as a testament to this era, its brass fittings gleaming with the patina of hopeful futility. These early devices were often repurposed military artillery, modified to fire blank charges skyward, creating the same "boomph" that still echoes across vineyards today. The 2007 model would be instantly recognizable to a farmer from 1901, differing only in minor refinements to the combustion chamber, a technological evolution comparable to replacing a rotary phone with a slightly shinier rotary phone. This stasis speaks volumes: when something works, it evolves; when it doesn't, it merely persists in slightly updated packaging, like a reality TV show that keeps getting renewed despite plummeting ratings.The cannon is just the latest iteration of a long-standing human impulse: to shout at the clouds and demand they listen.

The same applies to more modern gadgets. Some companies now sell electromagnetic devices that claim to alter local weather patterns by emitting frequencies that affect atmospheric ions. Others promote “rain rockets” that launch pyrotechnic flares into clouds. These are often marketed with scientific-sounding jargon but lack independent verification. Like the cloudbuster, they tap into a longing for control over forces that are otherwise unpredictable and immense. One manufacturer of hail cannons claims a 500-meter radius of protection, a figure that sounds precise until one realizes it has no basis in atmospheric modeling. The devices fire every few seconds, day and night, during storm season, creating a constant, rhythmic pounding that some neighbors describe as torture.

What remains is a catalog of human ingenuity, ambition, and occasional folly. The belief that a loud noise could stop hail, that metal tubes in water could summon rain, or that a secret chemical mixture could break a drought speaks to both the limits of knowledge and the reach of imagination. Through failures, by testing ideas, discarding the ones that collapse, and refining the ones that show promise, science moves forward, not just through discoveries. The hail cannon still stands in fields, firing its booming pulse into the sky. The cloudbuster remains a curiosity, a relic of mid-century esoteric thinking. Cloud seeding continues in various forms, cautiously applied where the risks seem worth the potential reward. And somewhere, a farmer watches the clouds, listens to the boom, and hopes.

Comments

Post a Comment