The Man Who Made Niagara Falls His Personal Playground—Then Abandoned His Wife for Fame

Charles Blondin, born Jean-François Gravelet in 1824 in Hesdin, Pas-de-Calais—though some early accounts misplace his birth in the more poetically named Saint-Germain-la-Blanche-Herbe—was a man whose life became synonymous with audacity, balance, and a kind of theatrical daring that blurred the line between human capability and outright madness. From an early age, he was immersed in the world of acrobatics and performance, less a whimsical diversion than a vocation carved into his bones. At five, he was sent to the École de Gymnase in Lyon, a training ground for prodigies where children were shaped into aerialists, tumblers, and contortionists under the stern gaze of instructors who believed discipline was the only path to grace. After just six months, he made his public debut as *The Boy Wonder*, a title that clung to him like sawdust to a leotard, and by nine, he had performed at the Cirque d’Été in Paris, a venue so prestigious it was reserved for only the most skilled and promising entertainers of the day. His training was rigorous, his discipline absolute. But it wasn’t until he crossed the Atlantic and set his sights on North America that he would transform from a skilled acrobat into a legend.

Blondin’s name—adopted early in his career, though he also performed as Jean-François Blondin, Chevalier Blondin, or simply *The Great Blondin*—was not just a stage moniker; it became a cultural shorthand. In Britain and beyond, the term "Blondin" eventually came to describe any tightrope walker, much like how "Hoover" became synonymous with vacuum cleaners. To walk a tightrope was to perform a Blondin act. His influence extended beyond the circus; industrial equipment used in Welsh slate quarries—an aerial ropeway for transporting stone across deep valleys—was named after him. The Blondin, as it was called, was a mechanical echo of his feats: a cable strung between points, carrying weight across empty space, defying gravity through tension and precision. It was a fitting tribute—one that honored not only his skill but also the idea that a single line could connect two impossible places, whether across a gorge or between spectacle and utility.

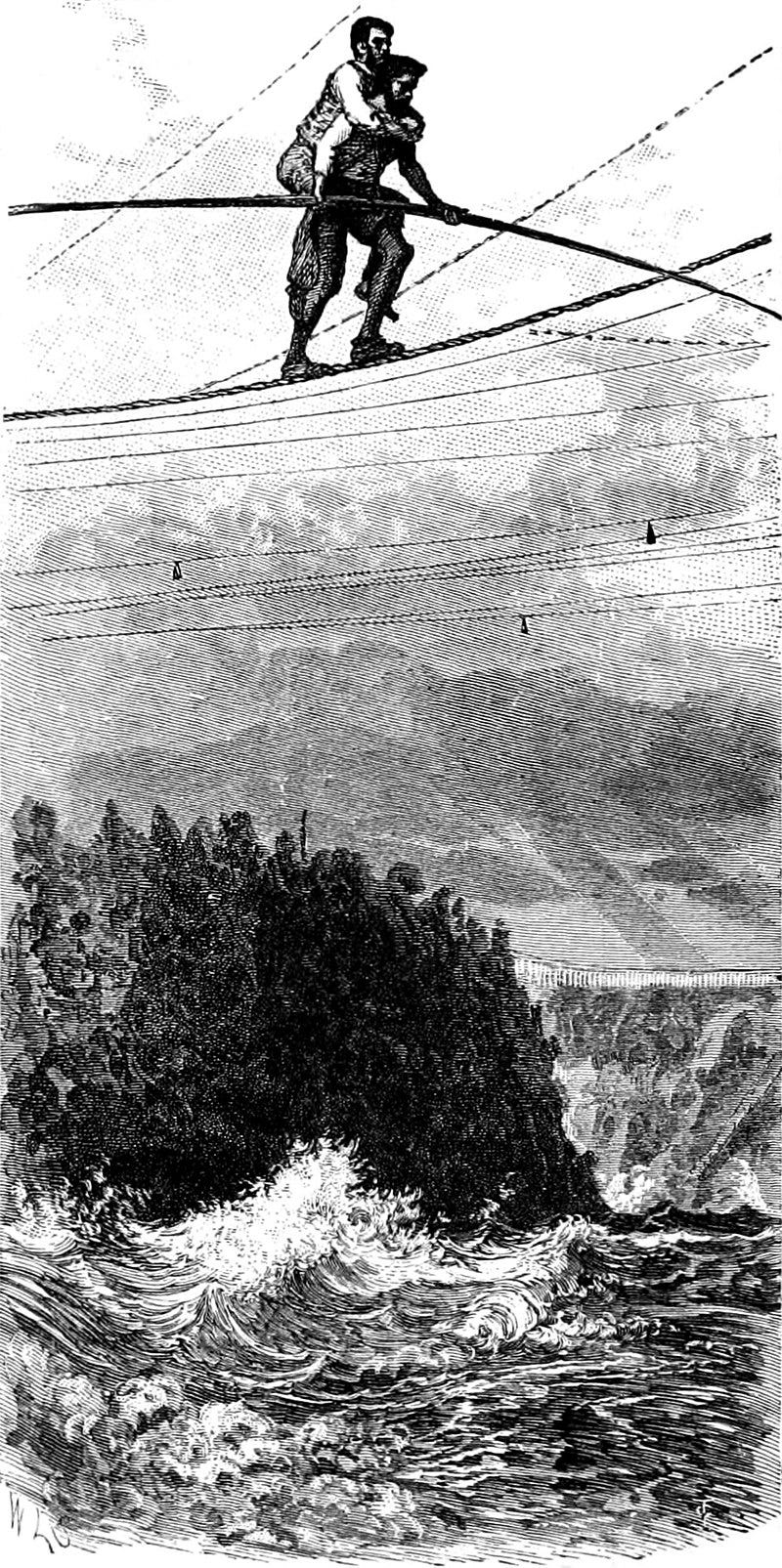

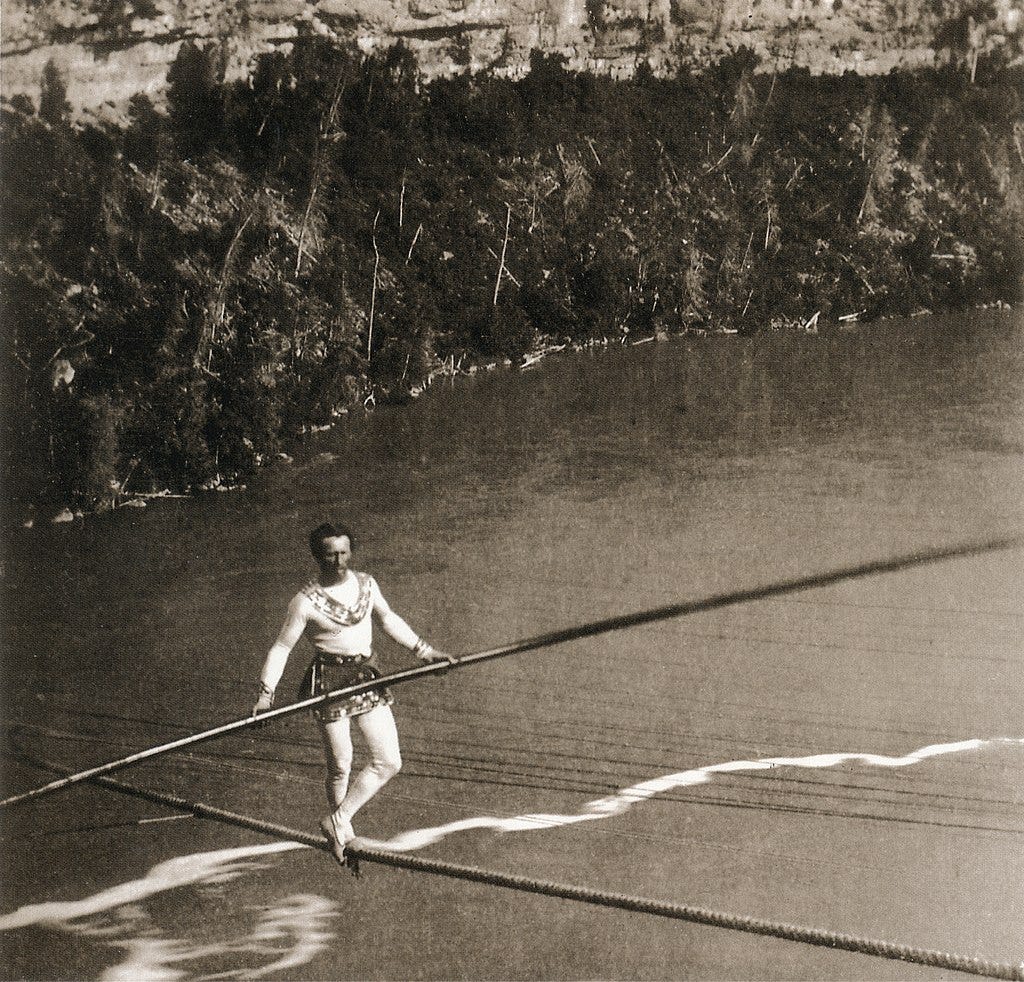

His most famous achievement was crossing the Niagara Gorge on a tightrope in 1859. The wire stretched 1,100 feet across the chasm—340 meters of hemp and hope—160 feet above the thundering water, anchored near what is now the Rainbow Bridge, though no bridge yet spanned the divide. The rope itself was 3.25 inches in diameter—roughly the width of a man’s hand—thick enough to grip, but not so wide as to offer any real margin for error. A single misstep, a moment of hesitation, a gust of wind, and the result would be a plunge into a churning cauldron of whitewater and rock. Yet Blondin didn’t just cross it once. He did it multiple times, each performance more elaborate than the last, each designed to deepen the public’s awe and disbelief.

The first crossing, on June 30, 1859, was impressive enough: a slow, deliberate walk, poles in hand, eyes fixed on the far side. He wore pink tights adorned with spangles, the lowering sun catching the fabric so he seemed to glow like a fallen star. His balancing pole, carved from ash, was 26 feet long and weighed nearly 50 pounds—a counterweight to both gravity and fear. As he stepped onto the cable from the American side, the crowd fell silent. Children clung to their mothers’ legs; women peeked from behind parasols; several onlookers fainted. About a third of the way across, he shocked the crowd by sitting down on the wire and calling for the *Maid of the Mist*, the famed tourist vessel, to anchor beneath him. He cast down a line, hauled up a bottle of wine, drank, and started off again, breaking into a run after he passed the sagging center, where the rope dipped to just 190 feet above the gorge. While the band played “Home, Sweet Home,” Blondin reached Canada. One man helped pull him ashore and exclaimed, “I wouldn’t look at anything like that again for a million dollars.”

The engineering behind Blondin's feat was as remarkable as the performance itself—though considerably less glamorous than the man in pink tights who would ultimately walk upon it. The hemp cable, three inches thick and 1,100 feet long, had been strung across the chasm using what might generously be called 19th-century ingenuity and a complete disregard for modern OSHA regulations. Initially, a light rope barely an inch thick was attached to one end of the massive cable, then conveyed across the river via a makeshift pulley system that looked suspiciously like something assembled from spare circus equipment. But securing it on the Canadian side presented a problem worthy of a particularly sadistic puzzle box: Blondin's assistants feared the light rope wouldn't bear the weight of the cable as it was drawn up the gorge. With characteristic flair, the rope dancer solved the dilemma himself. After tying another rope around his waist, he rappelled 200 feet on the small rope, attached it to the end of the cable, and then blithely climbed back to Canadian ground to secure the cable to a rock. One can only imagine the conversation that followed: "You mean to tell me we've been standing here wringing our hands while you could have done this in five minutes?" "Oui. Also, someone fetch me a glass of wine. Walking 200 feet down a rope is thirsty work."

To prevent excessive swaying (because nothing says "safety measure" quite like "excessive swaying"), guy ropes ran from the main cable at 20-foot intervals to posts on both banks, creating what one observer described as "a massive spider web of tension"—though presumably one that wouldn't collapse if a particularly ambitious fly tried to walk across it. Yet Blondin could do nothing about the inevitable sag in the center—approximately 50 feet of cable where no guy ropes could be attached. At that spot, midway across the gorge, he would be a mere 190 feet above the thundering water, closer to doom than at any other point on the crossing. It was, one might say, the tightrope equivalent of a pothole—only instead of damaging your suspension, it would send you to a watery grave while thousands watched and placed bets on how long you'd survive the plunge.

Blondin worked without a net, believing that preparing for disaster only made one more likely to occur—a philosophy that both endeared him to thrill-seekers and horrified moralists who presumably spent their evenings safely tucked in bed, dreaming of balanced ledgers and properly secured ladders. The New York Times condemned "such reckless and aimless exposure of life" and the "thoughtless people" who enjoyed "looking at a fellow creature in deadly peril." One suspects the editorial board had never seen a particularly exciting game of croquet. Mark Twain later dismissed him as "that adventurous ass," though one suspects the humorist secretly admired the Frenchman's audacity while simultaneously calculating how many drinks he could get out of telling the story at the next saloon gathering. Not everyone was convinced of his authenticity; an indignant resident of Niagara Falls insisted Blondin was a hoax, that "no such person in the world" could perform such feats. This was, presumably, the same gentleman who insisted the moon landing was faked because he himself couldn't jump that high.

After that first successful crossing,

Blondin didn't merely rest on his laurels—he doubled down on spectacle with the enthusiasm of a man who had discovered that the public would pay to see increasingly improbable things. On the Fourth of July, he appeared without his balancing pole (the tightrope equivalent of juggling chainsaws while riding a unicycle), walking backward halfway across before lying down on the cable, flipping himself over, and continuing in reverse. On another occasion, he strapped a Daguerreotype camera to his back, advancing 200 feet before affixing his balancing pole to the cable, untying the camera, and snapping a likeness of the American-side crowd. He then hoisted the camera back into place and continued his journey—a feat of precision that would have made a watchmaker weep with admiration and probably quit his job on the spot. Each crossing became more elaborate than the last, as if he were systematically dismantling the public's understanding of what was physically possible, one improbable stunt at a time.

The Dublin incident of 1860 served as a stark reminder of the very real dangers Blondin faced, though it's worth noting that Blondin himself remained miraculously unharmed while two workers fell to their deaths. While performing on a rope 50 feet above ground at the Royal Portobello Gardens, the cable snapped, causing the scaffolding to collapse. An investigation followed, with the judge placing blame squarely on the rope manufacturer rather than the performer—a decision that would have made any modern liability lawyer weep with envy. A bench warrant was issued when Blondin and his manager failed to appear at a subsequent trial—having already returned to the United States, where the Niagara performances had made him a fortune and presumably better legal representation. The incident did little to diminish his fame; if anything, it reinforced his almost supernatural reputation. As one contemporary put it: "Blondin walks where angels fear to tread, and survives where mere mortals perish." Or, as Blondin might have said while packing his bags for America: "When the rope breaks, always make sure you're the one holding the other end."

His technical innovations were as impressive as his stunts. In 1869, at London's Crystal Palace Harvest Fete, he traversed a rope on a specially designed bicycle with deeply grooved wheels to grip the cable—a contraption that looked like it had been dreamed up by a particularly ambitious drunk after three pints too many. The machine, crafted by Messrs. Gardiner and Mackintosh, had no weights or attachments—just pure balance and nerve, plus the implicit understanding that falling off a bicycle while 70 feet in the air would be considerably less dignified than simply walking. Decades before modern engineering would validate such feats, Blondin intuitively understood the physics of tension, counterbalance, and center of gravity—the kind of knowledge that comes from having nearly died enough times to develop an intimate relationship with the void below.

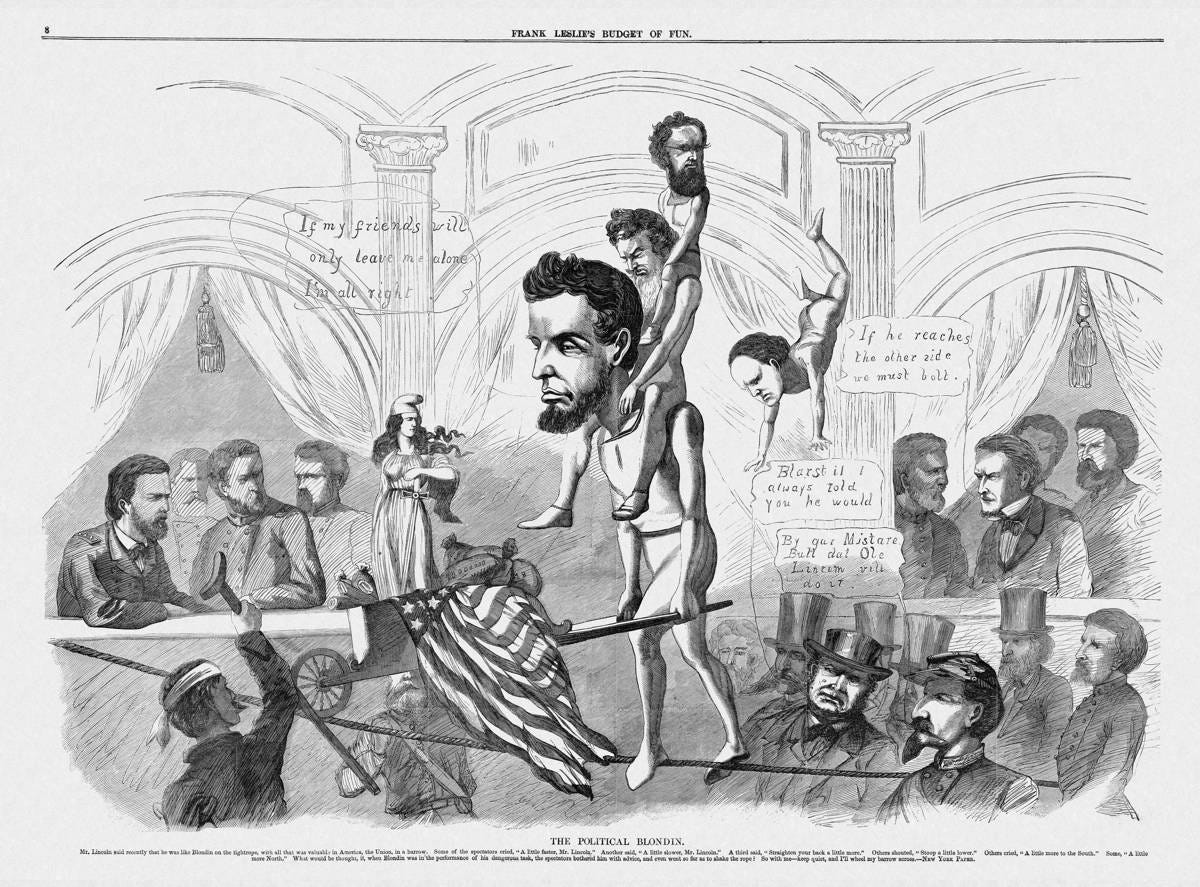

The political implications of his performances extended far beyond mere entertainment. During the 1864 U.S. presidential election, Abraham Lincoln compared himself to "Blondin on the tightrope, with all that was valuable to America in the wheelbarrow he was pushing before him." A political cartoon in Frank Leslie's Budget of Fun depicted Lincoln pushing that wheelbarrow while carrying two men on his back—Stanton and Welles—while foreign powers and generals looked on. The metaphor was perfect: the nation balanced on a thin line, the president the only one steady enough to cross. Blondin, whether dangling over Niagara or trundling a stove across a void, had become more than a performer. He was an archetype. A man who walked where others feared to stand. A poet of peril. A living metaphor for the precarious balance of a nation torn by civil war—and apparently, the only person in America who could be trusted not to drop the wheelbarrow.

But Blondin was not content with mere success. He was a showman, and spectacle was his currency. On subsequent crossings, he introduced variations that seemed pulled from the fever dream of a circus madman. He walked blindfolded. He walked backward. He pushed a wheelbarrow across the wire, and inside the wheelbarrow sat his manager, Harry Colcord, who reportedly trembled the entire way but emerged unharmed. Blondin himself remained calm, even cheerful, engaging the crowd with theatrical flourishes—bowing, pausing, even stopping mid-span to sit on a chair that had been balanced on the rope with only one leg touching the wire, the other three dangling over the abyss.

One of the most infamous stunts involved cooking an omelette in the middle of the crossing. He carried a small stove, a pan, and eggs with him. At the midpoint of the wire, he set up the stove, lit a flame, cracked the eggs, and fried them while suspended over the falls. The image is absurd, almost comical—until one considers the reality: a man balancing a heat source on a swaying wire, managing fire and food while the air around him vibrated with the roar of thousands of tons of water crashing below. There was no safety net, no harness, no second chance. Yet he did it with a kind of nonchalance, as if frying an egg hundreds of feet above certain death were a perfectly reasonable thing to do on a summer afternoon. On another occasion, he carried a table and chair, stopped in the middle, and attempted to sit down—only for the chair to tumble into the water. He nearly followed, but regained his composure, sat on the cable, and ate a piece of cake washed down with champagne.

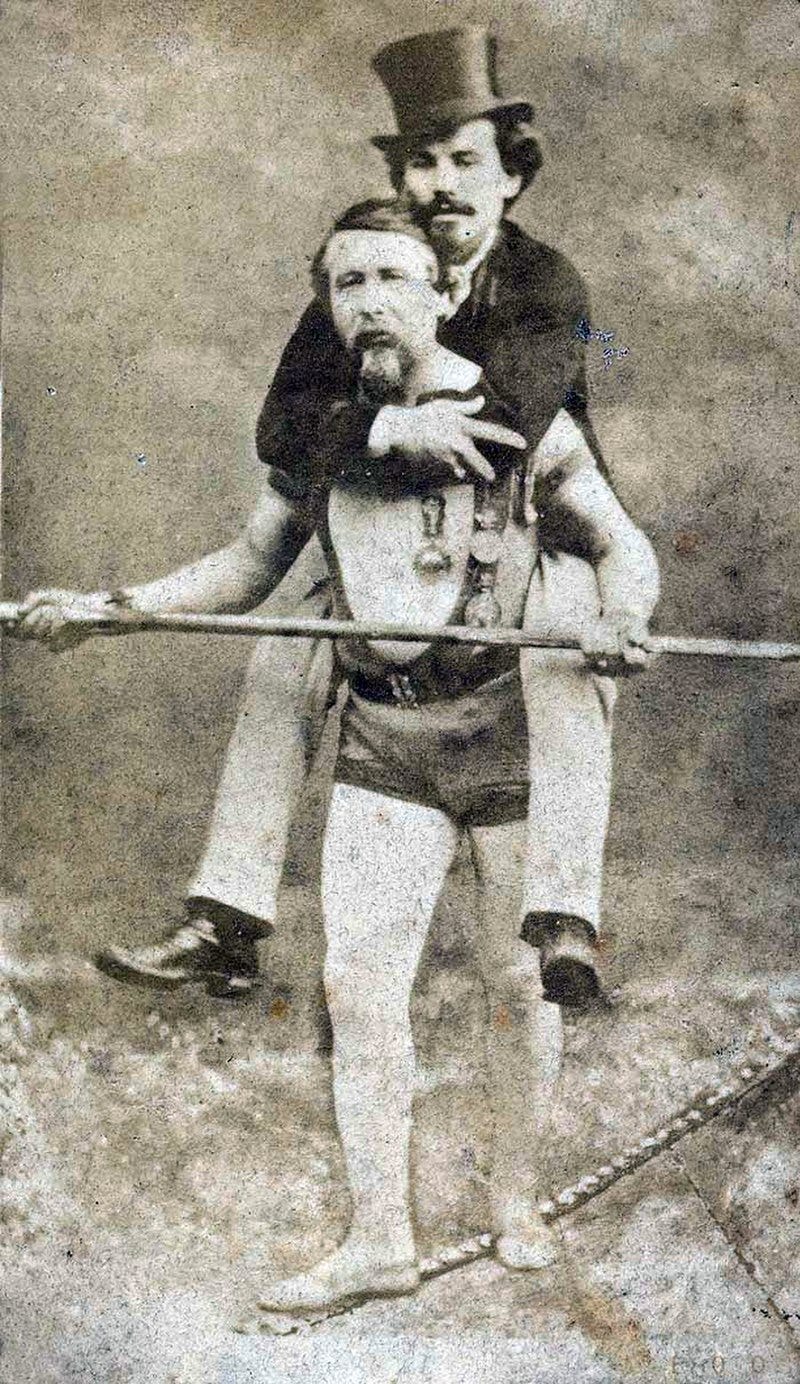

He wore disguises. He performed in a sack—draped over his upper body rather than wrapped around his legs like a child in a race—his arms and legs free to move while his vision was severely restricted. He walked on stilts across the wire, a feat so improbable that it defies belief even when documented. He carried people in wheelbarrows and even on his back. On one occasion, he transported Colcord piggyback, giving him strict instructions: “Look up, Harry… you are no longer Colcord, you are Blondin. Until I clear this place be a part of me, mind, body, and soul. If I sway, sway with me. Do not attempt to do any balancing yourself. If you do we will both go to our death.” A few of the guy ropes snapped along the way, but they made it. He crossed at night, a locomotive headlight affixed to either end of the cable. He crossed with his body in shackles. He crossed pushing a wheelbarrow filled with rocks to simulate weight. By the time he gave his final performance in 1896, it was estimated he had crossed Niagara Falls 300 times and walked more than 10,000 miles on his rope.

His personal life was as dramatic as his performances, though less documented. He married Marie Blancherie in France on August 6, 1846, legitimizing their son Aime Leopold before having two more children with her. But upon arrival in the United States, he married again—Charlotte Lawrence, an American woman, in Boston in 1852. Together they had five children: Adele, Edward, Iris, Henry Coleman, and Charlotte. The historical record is silent on what became of his first wife. There is no mention of divorce, no indication that she followed him across the Atlantic. Whether she was abandoned, divorced, or simply left behind in the wake of his rising fame is unknown. One can only imagine her reaction upon seeing newspaper illustrations of her former husband walking over Niagara Falls, pushing a wheelbarrow, cooking an omelette, now a transatlantic sensation while she remained in obscurity.

After years of triumphs in North America, Blondin returned to Europe, settling in England. He retired briefly, living off the earnings of his most lucrative years—his estate at death was valued at £1,832, equivalent to over £250,000 today. But like many performers of the 19th century, retirement did not suit him. The stage called, or perhaps the bank account dwindled. He re-emerged in the world of pantomime, a distinctly British form of theatrical entertainment known for its slapstick, music, and absurdity. In the 1893–94 season, he starred in a production of *Jack and the Beanstalk* at the Crystal Palace, organized by Oscar Barrett. He played no giant, no hero, but instead took the role of the front end of a pantomime horse—a comedown, or perhaps a final act of self-parody. The man who had defied gravity now pranced across a stage in a furry costume, neighing on cue, sharing the role with another performer who played the rear. There was no wire, no danger, no omelette—just applause for a name that still carried weight, even if the act no longer matched the legend.

Even in domestic life, the tightrope followed him. An anecdote, likely apocryphal but widely repeated, claims that when he did the washing, he hung the clothes on the line while standing on top of it, balancing as naturally as breathing. Whether true or not, the story persists because it fits. Blondin was not just a man who walked on ropes; he was a man for whom the rope was a natural surface, a second ground. His body had been trained to a degree of precision that made the impossible routine. The sway of the wire, the pull of the wind, the vibration of the crowd—these became part of the rhythm instead of serving as distractions.

His influence endured long after his final performance. The term “Blondin” took root, spreading from popular speech into industry. In the slate quarries of North Wales, where deep pits required materials to be moved across open space, cable systems were installed to transport stone from one side to the other. These systems, known as Blondins, were direct descendants of his feats—mechanical tightropes carrying weight over voids, relying on tension, balance, and careful engineering. The name was a tribute, a nod to the man who had proven that such crossings were possible, even if the context had shifted from spectacle to utility.

He never went over the falls. He walked over them, yes, but always with control, always with the wire underfoot, always with the ability to stop, turn, or retreat. His art lay in mastery over nature, never in surrender to it. He did not fall; he did not plunge. He stepped, one foot in front of the other, with a pole in each hand, a stove in one pocket, a manager in a wheelbarrow, an omelette sizzling in the pan. He did it in front of thousands, with newspapers chronicling every step, with skeptics offering bets, with engineers questioning the physics. And he did it again. And again. Until the wire was no longer just a rope, but a thread woven into the fabric of legend.

Even when the rope broke, as it did in Dublin in 1860 during a performance 50 feet above the ground, it was not Blondin who fell. The scaffolding collapsed, killing two workers, but he was unharmed. An investigation followed; the judge laid blame on the rope manufacturer, not the walker. A bench warrant was issued when Blondin and his manager failed to appear at a subsequent trial, having already returned to the United States. Yet the incident did little to dim his fame. In 1861, he appeared at the Crystal Palace in London, turning somersaults on stilts 70 feet above the ground. In 1873, he crossed Edgbaston Reservoir in Birmingham, a feat commemorated by a statue erected in 1992 on the nearby Ladywood Middleway. On August 3, 1896, at the age of 71, he walked across Waterloo Lake in Roundhay Park, Leeds, blindfolded on one pass and cooking an omelette on another. It was his final performance.

He died on February 22, 1897, twelve days before his 73rd birthday, from complications of diabetes at his "Niagara House" in Ealing, London. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, his grave marked with quiet dignity rather than a statue. He had never taken out life insurance—no one, he joked, would have underwritten the risk. Three years after his death, his third wife, Katherine James, the woman who had nursed him through a back injury in 1895 and married him at age 31, died of cancer at just 36. She had outlived him by only four years, a brief coda to a life lived on the edge.

And still, the name endures. In 1864, Abraham Lincoln compared himself to "Blondin on the tightrope, with all that was valuable to America in the wheelbarrow he was pushing before him." A political cartoon in *Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun* depicted Lincoln pushing that wheelbarrow, carrying two men on his back—Stanton and Welles—while foreign powers and generals looked on. The metaphor was perfect: the nation balanced on a thin line, the president the only one steady enough to cross. Blondin, whether dangling over Niagara or trundling a stove across a void, had become more than a performer. He was an archetype. A man who walked where others feared to stand. A poet of peril. A legend spun from rope and nerve.

Comments

Post a Comment