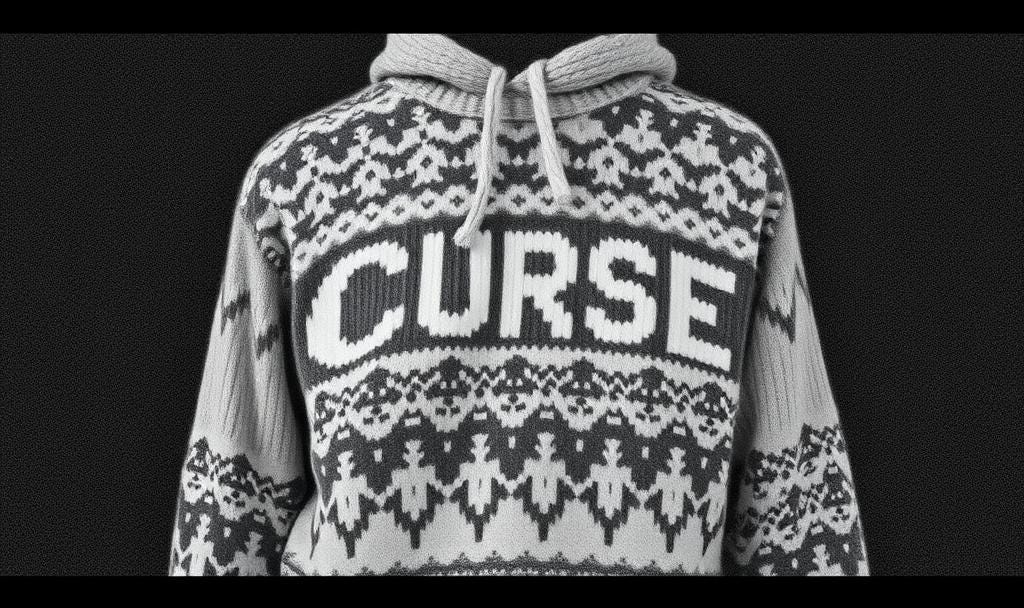

The Sweater Curse

The sweater curse, a phenomenon both whimsical and oddly specific, has long haunted the world of knitters, particularly those in romantic relationships. It is no traditional curse, there are no ancient incantations, no vengeful spirits lurking in tangled yarn. Instead, it is a superstition rooted in timing, effort, and emotional investment, as real to knitters as the ache in their wrists after a marathon knitting session. The belief is simple: if you knit a sweater for your significant other, the relationship will end, either before the sweater is finished or shortly after it is given. The curse does not discriminate by skill level, yarn quality, or pattern complexity. It strikes regardless of intent, often catching the knitter unaware, mid-purl, as their love life unravels faster than a dropped stitch in a lace shawl. Some claim it's mere coincidence; others swear it's as inevitable as a dropped stitch in garter stitch. In a 2005 poll, 15 percent of active knitters said they'd experienced the curse firsthand, while 41 percent considered it a serious possibility worth factoring into their romantic calculus.

Knitting a sweater is no small undertaking. It demands hours, sometimes weeks or months, of focused labor, up to a year for the particularly meticulous or distracted knitter. Wool is not cheap, especially if one opts for something soft, ethically sourced, or dyed in a shade that perfectly complements the recipient's eyes. The process involves swatching, measuring, adjusting, and occasionally ripping back entire sections when the gauge is off. It is, in every sense, a labor of love, so much so that the act itself may become a substitute for the relationship. The knitter, eyes fixed on the needles, may knit through conversations, knit during movie nights, knit while their partner tries to share news about their day. The sweater becomes a third presence in the relationship, silent but ever-present, growing steadily while emotional intimacy stagnates. This isn't just hobbyism; it's an investment of approximately 100,000 stitches and over $100 in materials, a physical manifestation of time and care that can't be easily undone.

One proposed mechanism for the sweater curse is misdirected attention. The knitter, absorbed in the rhythm of knit and purl, may neglect their partner. The sweater, meticulously crafted, begins to symbolize more than a gift, it becomes a competitor. The partner, left to their own devices, may begin to wonder where they stand in the hierarchy of the knitter's affections. Is the sweater loved more than I am? Does my partner care more about stitch consistency than date night? These questions fester, unspoken, until one day the relationship simply stops, like a yarn end left untied. It's a phenomenon that would have made perfect sense to the women of the French Revolution, who reportedly knitted as they watched the guillotine do its work, stitching away while relationships, and heads, were severed. There's something almost sinister about the repetitive motion, the way it can occupy the hands while the mind wanders elsewhere, much like the two women knitting black wool in Conrad's "Heart of Darkness," guarding "the door of Darkness" with their silent, ominous craft.

Another factor is the sheer amount of time involved. Relationships, especially new ones, are fragile in their early stages. The honeymoon phase, fueled by dopamine and novelty, typically lasts around 18 months. If a sweater takes longer than that to complete, it may outlive the romance that inspired it. The knitter, unaware of the ticking clock, continues to knit, adding rows as the relationship quietly deteriorates. By the time the sleeves are finished, the recipient may have already checked out emotionally. The sweater arrives like a postcard from a vacation that never happened. This is what some call "unlucky timing", the relationship dies of natural causes during the sweater’s making, like those Egyptian socks from the eleventh century that survived simply because their owners stopped walking long enough for archaeologists to find them centuries later, rather than because they were particularly well-made. Knitting has always been a nomadic craft, requiring only yarn and needles, perfect for following the migrations of game or the seasonal ripening of fruits, but perhaps not so perfect for following the unpredictable migrations of the human heart.

Then there is the issue of fit. Knitting a garment to precise measurements requires honesty, both from the knitter and the recipient. But asking someone for their chest, waist, and hip measurements can feel intrusive, even clinical. Many knitters avoid the conversation altogether, guessing based on memory or estimates, which often leads to a sweater that is too tight, too loose, or somehow both. The recipient, presented with a garment that does not fit, may feel judged. Was I too fat when you measured me in your head? Did you think I'd shrink by the time you finished? Even if the sweater fits perfectly, the act of receiving something so personal can be overwhelming. It is not just a piece of clothing; it is a physical manifestation of someone's time, care, and expectation. The weight of that can be difficult to carry, especially when you consider that in nineteenth-century literature, good women knit while bad women crochet. Jane Fairfax in "Emma" knits dutifully; Becky Sharp in "Vanity Fair" crochets to show off her fingers. To receive a hand-knit sweater is to be cast as the virtuous one in someone else's romantic novel, whether you want that role or not.

This historical baggage clings to hand-knit garments like lanolin to raw wool. Consider the Egyptian socks from the eleventh century, those rare archaeological survivors that prove knitting's ancient lineage. They weren't merely functional foot coverings but status symbols, their intricate patterns revealing the wearer's position in society. Even then, a poorly fitting sock could signal social misstep as surely as a modern sweater that bunches at the shoulders. The craft has always carried this dual nature: practical necessity intertwined with social signaling. During World War II, when patriotic knitters produced those death's-head helmets with eye and mouth holes (the kind that once terrified a young Alison Lurie in her Unitarian Church), the garments served both purpose and propaganda. Soldiers received socks that would keep their feet warm in the trenches, but also sweaters that whispered, "Someone at home is thinking of you", a message that could be as comforting as it was burdensome. One can imagine the recipient thinking, Must I wear this lumpy creation that smells faintly of mothballs and maternal anxiety, knowing it represents hundreds of hours of someone's undivided attention?

Knitting's nomadic origins explain much about its emotional weight. Unlike weaving, which demands a settled environment and bulky equipment, knitting requires only yarn and needles, perfect for following migrations of game or seasonal harvests. But this portability came with psychological consequences. The knitter could work anywhere, yes, but also would work anywhere, fingers moving automatically while the mind wandered elsewhere. It’s no coincidence that in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the two women knitting black wool outside the Company office represent both domestic industry and fate itself, “guarding the door of Darkness,” as Marlow observes, their rhythmic clicking a metronome counting down to doom. This association between knitting and mortality stretches back centuries. During the French Revolution, women famously knitted as they watched the guillotine do its work, their needles clicking in time with falling heads. Dickens immortalized this macabre tradition in "A Tale of Two Cities" with Madame Defarge, who encoded victims' names in her stitches, a particularly insidious form of pattern writing where the wrong cable twist could mean life or death. Modern knitters may not be plotting executions, yet the psychological residue lingers: the sense that every stitch contains meaning, that the rhythm of knit and purl is somehow measuring time’s steady march toward an inevitable conclusion.

The class distinctions embedded in textile arts further complicate the sweater curse. In nineteenth-century literature, as Lurie notes, good women knit while bad women crochet, a distinction rooted in knitting's practical origins versus crochet's status as "fancy work." Jane Fairfax in "Emma" dutifully knits while Becky Sharp in "Vanity Fair" shows off her fingers with fine netting. This hierarchy persisted well into the twentieth century, when knitting for the troops during wartime became a patriotic duty, transforming what might have been dismissed as "women's work" into essential national service. Yet even as knitting gained respectability through wartime contributions, it never entirely shed its domestic connotations. A hand-knit sweater still carries that whiff of permanence, of settling down, of becoming someone's "number one husband" in a way that a store-bought garment never could. The very act of measuring someone for a sweater, taking their chest, waist, and hip dimensions, echoes the intimate measurements taken by seamstresses of centuries past, who knew their clients' bodies better than most lovers ever would.

There's also the matter of knitting's physical demands, which modern knitters often underestimate. Victorian knitters used steel needles so fine they could produce garments of astonishing delicacy, but at the cost of frequent hand cramps and eye strain. Today's knitters might choose ergonomic bamboo needles and well-lit workspaces, but the fundamental physical toll remains. After hours of repetitive motion, the hands ache; the shoulders tighten; the neck stiffens. This physical investment becomes part of the emotional equation, the recipient isn't just receiving a garment but the physical manifestation of someone's discomfort, someone's willingness to endure pain for their sake. It's no wonder some partners feel uneasy accepting such a gift; it's like being handed a love letter written in blood.

Even the materials themselves carry historical weight. Wool, the traditional medium of choice, has its own complicated history. For centuries, it was the fiber of the common people, while silk and linen belonged to the upper classes. The process of transforming raw fleece into wearable yarn involved multiple stages, shearing, washing, carding, spinning, each requiring skill and labor. When a modern knitter selects "ethically sourced" merino wool, they're participating in a chain of production that stretches back to medieval sheep farmers and cottage industry weavers. Every skein contains this lineage, this history of labor and care. No wonder a hand-knit sweater feels so heavy, it's carrying centuries of textile tradition on its stitches.

Some recipients simply do not like sweaters. They may find wool itchy, jumpers unfashionable, or the idea of wearing something handmade by their partner uncomfortably intimate. "Why are you knitting me a jumper?" they might ask. "I look s*** in jumpers and I don't like them, and I don't like wool." And then, without pause, "And I don't like you, bye." The sentiment may be expressed less bluntly, yet the effect remains the same. The gift, intended as a gesture of affection, becomes a symbol of mismatched expectations. The knitter, blindsided, is left holding a half-finished sweater and a broken heart. There's historical precedent for this aversion, during World War II, when patriotic knitters produced those death's-head helmets with eye and mouth holes, even the most grateful soldiers probably wondered if it was worth the social embarrassment. A hand-knit garment, no matter how well-intentioned, can subject its wearer to ridicule, either because it looks bad or conveys overly domestic connotations that make them feel trapped. In the words of one knitter's nightmare scenario: "You've just knit me a love shroud."

There is also the possibility that the relationship was already failing. The sweater, in this case, serves as a symptom rather than a cause. The knitter, sensing the distance, throws themselves into the project as a rescue mission. If I make them something beautiful, they'll remember why they loved me. The heart-shaped cable pattern, the carefully chosen color, the hidden message in the intarsia, it all becomes a plea, stitched row by row. But love cannot be knitted back into existence. The sweater may be flawless, but it cannot mend what is already torn. This is the cruel irony of the sweater curse: the very act of trying to save a relationship can accelerate its demise. It's like the character in "Anna Karenina" who crochets nervously while confronting her lover, Anna's hands move automatically while her heart breaks, the stitches accumulating as her relationship unravels. The knitter, too, may find themselves mechanically repeating the same motions while their emotional world collapses around them.

In some cases, the sweater acts as a catalyst, forcing the recipient to confront the state of the relationship. Holding a garment that represents hundreds of hours of labor, they may ask themselves: Do I deserve this? Am I giving enough in return? The imbalance becomes glaring. One person has invested immense time and emotion into a single object, while the other has contributed little beyond occasional compliments on the progress. The sweater, once a symbol of love, now highlights the asymmetry. The recipient may not even realize it until they are standing in their living room, holding a hand-knit cardigan, and thinking, What the f*** am I doing here? This is what knitting literature calls "a catalyst for analyzing the relationship", the gift may seem too intimate, too domestic, or too binding. It can be a signal that makes them realize the relationship isn't reciprocal, prompting them to end things before it involves obligations. Or, as one knitter put it after her boyfriend left, "He didn't break up with me because of the sweater. He broke up with me because of what the sweater revealed."

The domestic connotations of a hand-knit sweater can also be a turnoff. In some cultures, such a gift carries the weight of permanence, of settling down, of becoming someone's "number one husband" or "official girlfriend." For partners who are not ready for that level of commitment, the sweater may feel like a trap. It is not just a piece of clothing; it is a statement. It says, I see a future with you. I am willing to spend months making you something you'll wear for years. That kind of declaration, even if unspoken, can be overwhelming. The recipient, feeling pressured, may retreat. This is why many experienced knitters advise matching the knitted gift to the stage in the relationship, beginning with hats, mittens, scarves, or socks before graduating to sweaters. Some even wait until marriage before making a sweater for a significant other, treating it as a symbolic garment for an already-established commitment rather than a proposal of one. After all, as the old knitting adage goes: "Never knit your man a sweater unless you've got the ring."

Then there is the question of permission. Many knitters operate under the assumption that a surprise sweater is a romantic gesture. But surprises, especially ones that involve wearing something, are risky. What if the recipient hates the color? What if they already have ten sweaters and have no use for another? What if they are trying to maintain a minimalist wardrobe? Knitting a sweater without asking is like planning a vacation for someone without consulting their schedule or preferences. The effort is appreciated in theory, but the execution can feel invasive. The advice, then, is simple: ask first. Involve the person in the process. Choose the yarn together. Discuss the style. Make it a shared project rather than a unilateral declaration of love. This isn't just practical advice, it's emotional self-preservation. Common-sense wisdom from knitting periodicals suggests determining whether the recipient would ever wear a hand-knitted sweater in the first place. Some people, it turns out, would rather go naked in winter than wear something handmade, no matter how beautifully crafted.

The sound of knitting needles clicking together, the soft rustle of wool, the occasional dropped stitch caught just in time, these are the rhythms of a craft that demands patience. But when that craft intersects with love, the stakes rise. A sweater is not just a garment. It is time made tangible, emotion spun into fiber. It can warm the body, but it can also expose the cracks in a relationship. Some knitters swear by the curse, warning others to stick to scarves or mittens. Others dismiss it as coincidence, a pattern mistaken for causation. Still others knit on, undeterred, believing that the right person will appreciate the effort, that love and wool can coexist without unraveling. There's even an old superstition that knitting a deliberate mistake into the sweater will break the curse, though most knitters report this rarely works, much like trying to fix a broken relationship by pretending not to care.

The sweater curse doesn't just happen, it creeps in, like a rogue purl stitch in a sea of knits, quietly unraveling everything. It's not the sweater's fault, really. It's more like the sweater shows up wearing emotional baggage and a passive-aggressive cable pattern. You think you're just making a nice gift, but somewhere between row 47 and sleeve shaping, you've accidentally knit a 3D model of your relationship anxieties. The recipient, meanwhile, is just trying to enjoy their life, and suddenly, bam, they're handed a woolen monument to devotion that took longer to make than their last holiday. "Here," you say, beaming, "I stayed up every night for six months so you could have this slightly lopsided turtleneck." They smile, but inside they're screaming, I didn't sign up for this level of emotional embroidery!

And let's be honest, some people don't even like jumpers. They tolerate them at Christmas, maybe, under duress. Now you've gone and made one specifically for them, with your love in every stitch, and their first thought is, Oh god, how do I fake warmth without wearing this? Do they wear it once a year like a cursed heirloom? Do they donate it and live in guilt? The sweater becomes a silent judge hanging in the closet. You didn't appreciate me, it whispers. I was hand-spun and you didn't even try. Some knitters now treat sweater projects like high-risk operations, requiring consent forms, fitting sessions, and exit strategies. Others just knit them for goats now. Safer. Less drama. Goats don't break up with you. They just chew the yarn. Next time you're tempted to knit a sweater for your lover, ask yourself: Do they deserve this? Or do they just deserve you, without the wool, the guilt, and the passive-aggressive cables? Remember what Miss Marple knew all along: sometimes the most dangerous thing isn't the knitting needle, but what you've been knitting toward all along.

Comments

Post a Comment