They Flew Planes Into Hurricane Eyes and Tried to Punch Them With Chemicals—It Didn't Work

Operation Popeye was a real U.S. military program that ran from 1967 to 1972, during the Vietnam War, and its goal was not to convert enemy soldiers to Catholicism, despite the name. It was not a covert mission to distribute papal indulgences or install tiny cardinals in jungle outposts. No, Operation Popeye was about weather. Specifically, it was about making it rain. A lot. On purpose. Over parts of Laos and Vietnam, particularly along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, where North Vietnamese supply convoys moved through dense jungle terrain like ants dragging a discarded sandwich across a picnic blanket.

The idea was simple, if slightly mad: extend the monsoon season. Not just let it happen, *enhance* it. Make the roads so muddy that trucks would sink into the earth like they’d personally offended it. Trigger landslides. Wash out river crossings. Basically, turn the entire supply route into a slow-motion swamp disaster, all without dropping a single bomb. The tool for this? Cloud seeding. That’s right, planes flying into clouds and dumping silver iodide and lead iodide like some kind of atmospheric seasoning. Sprinkle a little here, stir the atmosphere, and boom: instant downpour. It’s like cooking, but with more geopolitics and less Gordon Ramsay yelling.

This wasn’t some backyard experiment dreamed up by a rogue meteorologist with a grudge against dry weather. The science had been simmering for years. It was nurtured in the dry winds of California’s Mojave Desert at the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, where early weather modification research took root. Military engineers and civilian scientists watched over this work. They believed the sky was a canvas. The techniques were refined in the turbulent skies of Okinawa, tested in the typhoon-prone waters near Guam, and even studied in the humid sprawl of the Philippines and the hurricane-battered coasts of Texas and Florida, places where nature already knew how to throw a tantrum. The knowledge gained there fed directly into Operation Popeye, which became the operational arm of a broader, classified ambition: to weaponize the atmosphere.

The 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron handled the job, which sounds like a band that plays obscure prog rock at air force reunions, but was in fact a real unit flying real missions into real storms. Based out of Udon Thani Royal Thai Air Force Base, a sprawling, dusty compound in northeastern Thailand where the air shimmered with heat and the smell of jet fuel hung like a permanent fog, the squadron operated under the guise of routine weather reconnaissance. Officially, they were gathering data, filing reports, doing the unglamorous work of tracking tropical systems and monsoon fronts. Unofficially, they were waging a quiet war against gravity, friction, and the laws of hydrology. Inside the unit, the operation had a code name: *Motorpool*. It was the kind of bland, bureaucratic moniker that could hide in plain sight, like a spy using the alias “Accountant Jones.” Only those in the know understood that Motorpool wasn’t about vehicles, it was about making the earth itself rise up and swallow them.

Their slogan? “Make mud, not war.” Which is either brilliantly ironic or completely missing the point, depending on how you feel about using weather as a weapon. Because, let’s be honest, making mud *is* war, just war with worse footwear. You aren't shooting anyone. That's true. However, you are still sabotaging their ability to move, eat, or stay dry. It’s warfare by dampness. And it worked. At least, technically. Declassified reports say that 82% of the seeded clouds produced rain shortly after treatment. That’s a pretty solid batting average for something that involves trying to boss around the sky. Did the enemy notice? One imagines a North Vietnamese truck driver, knee-deep in sludge, looking up at the endless rain and muttering, “Huh. Must be climate change.” Except it wasn’t climate change. It was the U.S. military, up in the clouds, playing god with a chemistry set and a plane.

The operation ran from March 1967 through November 1972, covering every rainy season in Southeast Asia with a relentless rhythm. Two C-130 Hercules aircraft and two F-4C Phantom jets took off twice daily, streaking across the skies of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam like metallic birds of ill omen. The C-130s, hulking and utilitarian, carried the seeding agents in modified dispensers mounted along their fuselages, while the Phantoms, sleek, fast, and more accustomed to dogfights than meteorology, provided escort and high-speed atmospheric readings. The crews, rotated in from Guam, were seasoned weather jockeys, trained to read cloud formations like ancient runes and to fly through turbulence that would make a roller coaster look tame. They weren’t just pilots; they were storm whisperers, deploying silver iodide flares into the updrafts of cumulonimbus clouds, hoping to trigger a chain reaction of ice nucleation that would collapse the moisture-laden air into a deluge.

The government of Laos, meanwhile, had no idea any of this was happening. They weren’t asked. They weren’t told. No polite note: “Dear Laos, we’ll be increasing precipitation in your airspace this week. Sorry for the inconvenience. Sincerely, USA.” Nothing. Just American planes buzzing over, dumping iodides like aerial litterbugs, and making the rainy season extra rainy for reasons that were, at the time, highly classified. It was less “diplomatic coordination” and more “meteorological sneak attack.” Even within the U.S. government, the operation was a closely guarded secret. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird, when questioned by Congress, flatly denied that any such program existed, while Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the CIA quietly pulled the strings from behind the scenes. It was the kind of bureaucratic sleight of hand that only works when everyone agrees to pretend the elephant in the room is just a particularly large shadow.

When the operation was eventually exposed in the 1970s, people were not thrilled. The idea of one country secretly altering the weather over another’s territory struck many as *slightly* over the line. It isn't quite as bad as nukes. Still, it definitely falls into the "wait, you can do that?" category.” category. The revelation came first through a column by investigative reporter Jack Anderson in 1971, who called it *Intermediary-Compatriot*, a name so bland it could have been a tax shelter. Then came the *New York Times* in July 1972, with Seymour Hersh’s explosive report: “Rainmaking Is Used As Weapon by U.S.” The public reaction was a mix of awe and horror. Congress held hearings in 1974, where scientists and generals sat side by side, debating the ethics of turning clouds into weapons. The Pentagon Papers had already shaken faith in government transparency; now, it turned out, the U.S. had been *raining* on its enemies in secret. This outrage helped lead to the creation of the Environmental Modification Convention in 1977, a treaty banning the hostile use of environmental modification techniques. It’s sometimes called the ENMOD Convention, but its unofficial name, and the one that should be on all merchandise, is the Weather-a-bugger-about-y Treaty.

Try saying that five times fast: The Weather-a-bugger-about-y Treaty. The Weather-a-bugger-about-y Treaty. It’s like a tongue twister designed by a drunk meteorologist. The treaty prohibits using weather as a weapon, no more cloud seeding to flood enemies, no summoning tornadoes on Tuesdays, no freezing Beijing just because you lost a trade negotiation. It also banned the use of herbicides in warfare, which finally put an end to the widespread spraying of Agent Orange. So, silver lining: at least we stopped poisoning the countryside while trying to win hearts and minds.

But the U.S. government didn’t stop there. Oh no. If you thought cloud seeding in a war zone was ambitious, wait until you hear about Project Storm Fury. Running from 1962 to 1983, this was the government’s attempt to *weaken hurricanes* by flying planes into them and dumping silver iodide into the eyewall. The logic? Introduce the seeding agent, cause supercooled water to freeze, disrupt the storm’s heat engine, and, voilà, downgrade the hurricane from “catastrophic” to “merely inconvenient.” It was like trying to defuse a bomb by tickling it.

The roots of Storm Fury reached back to the 1940s, to a moment when science first believed it could bend the sky to its will. Vincent Schaefer and Irving Langmuir, researchers at General Electric, had discovered that dumping dry ice into a cloud could trigger snowfall, a breakthrough that sparked a wave of enthusiasm for weather control. Their work led to *Project Cirrus*, the first serious attempt to modify a hurricane, which ended in disaster when a seeded storm veered toward Savannah, Georgia, and the public blamed the scientists for playing God. Lawsuits were threatened, Langmuir gave impassioned speeches about human dominion over nature, and the project was quietly buried, only to rise again over a decade later, reborn as Storm Fury.

And really, when you think about it, the whole idea of taming a hurricane with a few well-placed canisters of silver iodide is less “bold scientific endeavor” and more “trying to calm a grizzly bear by throwing it a snow cone.” But in the 1940s, fresh off the high of having split the atom and convinced that every problem could be solved with enough engineers and elbow grease, the U.S. government looked at nature’s most violent storms and said, “We can fix that.” Or at least, Irving Langmuir said that. Repeatedly. And loudly. Langmuir, a Nobel Prize-winning chemist with the enthusiasm of a carnival barker and the subtlety of a thunderclap, became convinced after a few early cloud-seeding successes that humans weren’t just in the weather, we were above it. He reportedly once declared, “We’re going to control the weather, no more droughts, no more floods, just perfect blue skies and gentle breezes whenever we want them.” It’s the kind of quote that sounds inspiring until you realize he probably said it while adjusting a bowtie made of barometric charts.

His partner in meteorological madness was Vincent Schaefer, a self-taught scientist who, in 1946, discovered that tossing dry ice into a cloud could make it snow. Which, sure, sounds great if you’re planning a winter wedding in Arizona, but Schaefer and Langmuir saw bigger possibilities. Like, say, diverting hurricanes. Their first major test came with Project Cirrus, a joint military-industrial experiment that sounds like a rejected Bond villain plot. In 1947, they intercepted Hurricane Cape Sable, a storm already heading out to sea, minding its own business, and dumped 180 pounds of crushed dry ice into its rainbands. The cloud deck, as the report delicately put it, “exhibited pronounced modification.” Then the hurricane did something truly alarming: it changed direction and plowed into Savannah, Georgia.

Now, correlation isn’t causation, but when you’ve just thrown a ton of dry ice into a storm and it suddenly veers toward a major city, maybe don’t go on the radio claiming you’ve “harnessed the tempest.” Langmuir did exactly that, declaring the reversal proof of human mastery over the atmosphere. The public, less impressed, blamed the seeding. Lawsuits were threatened. The U.S. military, eager to avoid being sued by an entire coastal city, quietly shelved the project. The official line? “Nope, never happened.” It took twelve years for the government to admit, in a small newspaper article, that yes, okay, they might have poked the hurricane with a very cold stick. Project Cirrus was canceled, and the dream of weather control went underground for over a decade, surviving only in classified memos and the fever dreams of meteorologists with too much time and funding.

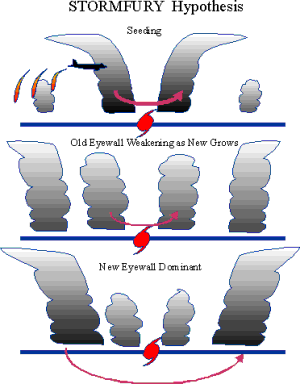

When it returned, it returned with flair: Project Stormfury. The new plan was more sophisticated, instead of dry ice, they’d use silver iodide, fired from wing-mounted dispensers like some kind of atmospheric artillery. The theory was elegant: seed the eyewall, trigger freezing, disrupt the heat engine, and gently persuade the hurricane to calm down, like a tantrum-throwing toddler offered a juice box. The first real test came in 1961 with Hurricane Esther, a storm that politely weakened by 10% after seeding. The next day, when the planes missed the target and nothing happened, scientists nodded sagely and declared the experiment a success. This is how science works: when it works, it’s proof; when it doesn’t, it’s data.

Then came Hurricane Debbie in 1969, the storm that would make or break Stormfury. Debbie was perfect: far from land, intensely organized, and willing to cooperate. Over two days, thirteen planes dove into its fury, dropping silver iodide like confetti at a storm’s birthday party. Winds dropped by 31%, then 18%. The eyewall collapsed. A new one formed. It was, by every measure, a triumph. The scientists were ecstatic. Plans were drawn up for a massive expansion. One researcher reportedly said, “We’re not just studying hurricanes anymore, we’re training them.”

Of course, it turned out Debbie was just doing what hurricanes do naturally. Later research revealed that unseeded storms often undergo the same “eyewall replacement cycles” that had been hailed as proof of success. It was like praising a dog for sitting when it was just lying down to nap. The whole premise began to unravel faster than a monsoon-soaked sandcastle. By the 1970s, the Navy had bailed, budgets were slashed, and the remaining P-3s were repurposed for actual science, like, you know, not trying to fight God with a flare gun. There was even a plan to move the operation to the Pacific and start seeding typhoons out of Guam, but China and Japan both said, in their own diplomatic ways, “Please don’t.” Japan, in particular, pointed out that typhoons provide over half their annual rainfall, so canceling them might, just slightly, cause a drought. Whoops.

And then there was Fidel Castro, who, upon hearing about Stormfury, allegedly declared it was a CIA plot to weaponize hurricanes and fling them at Havana like nature’s ICBMs. Which, given the era, wasn’t the wildest theory. For all we know, someone in a Pentagon basement did sketch a plan titled “Operation Heatwave Salsa.” But no, Stormfury wasn’t a weapon. It was something rarer: a $4 million-a-year (in 1975 money) experiment built on a beautiful, noble, and utterly incorrect assumption. That nature would listen. That you could bribe a cyclone with a little silver iodide and a firm handshake. That the atmosphere, for all its chaos, might just play along.

The aircraft used were Lockheed P-3 Orions, big, boxy, four-engine turboprops that looked like they were designed by someone who thought airplanes should resemble filing cabinets. Not exactly the sleek, futuristic craft you’d imagine battling nature’s fury. More like the kind of plane your uncle might charter to go duck hunting. But in they went, flying directly into the heart of hurricanes, releasing silver iodide like they were seasoning a giant atmospheric stew. The best data came from Hurricane Debbie in 1969, a storm so perfectly behaved it might as well have been scripted. Seeded twice, it responded with textbook precision: winds dropped by 31% and 18% on successive days, the eyewall collapsed, and a new, broader one formed, exactly as the theory predicted. The scientists were ecstatic. Plans were drawn up for a massive expansion. But nature, as it turns out, doesn’t read textbooks.

One can only imagine the pre-flight briefing: “Alright, team, today we’re flying into the eye of Hurricane Ella. Same procedure, drop the iodide, collect data, try not to die. And someone tell the guy in the back to stop playing *Yakety Sax* on the recorder. This is a serious scientific mission.” There may or may not have been a Slim Pickens impersonator on board, yelling “Wahoo!” as they broke through the eyewall. But the truth is, the missions were grueling, dangerous, and often fruitless. Hurricane Ginger in 1971 was the last attempt, seeded despite being too diffuse to respond, and it did nothing. By then, the Navy had pulled out, budgets were shrinking, and the dream of taming hurricanes was fading like a storm over open water.

Despite the effort, Project Storm Fury didn’t actually work. Hurricanes kept forming, intensifying, and making landfall with the same destructive enthusiasm as before. Later research showed that hurricanes contain far less supercooled water than scientists originally believed, which kind of ruined the whole premise. It’s like planning a firework display only to realize you’ve been handed a box of wet matches. All that flying, all that data, all that bravery, just to discover that nature had no intention of playing along. Worse, scientists realized that unseeded hurricanes often underwent the same structural changes, eyewall replacement cycles, that had been hailed as proof of success. The storms weren’t being weakened; they were just doing what storms do.

But, and this is important, it wasn’t a total loss. While the hurricane-weakening part failed, the project generated a mountain of valuable meteorological data. Scientists learned more about storm structure, wind patterns, pressure gradients, and eyewall dynamics than they ever had before. Forecasting models improved. Warning systems got better. So while the U.S. government didn’t figure out how to punch hurricanes in the face, they did learn how to predict when and where they’d show up, which is almost as good. It’s like going into a bar fight planning to win, but ending up just learning how to dodge better.

The legacy of these programs, Operation Popeye, Project Storm Fury, is a mix of audacity, absurdity, and accidental science. They reflect a time when the U.S. government looked at the sky and said, “We can improve this.” Not just study it, not just predict it, *control* it. If the Soviets had nukes, America would have rain. If hurricanes were a problem, well, maybe we could just *ask* them to calm down, with the help of a P-3 Orion and a tank of silver iodide.

There’s something almost cartoonish about it all. A squadron of planes flying around, making it rain on command. A fleet of aircraft diving into hurricanes like they’re trying to spoil the party. The slogans. The secrecy. The complete lack of consultation with the actual countries being rained upon. It’s like a *Mission: Impossible* episode written by someone who failed meteorology but really loved Cold War spy thrillers.

And yet, for all the humor, there’s a seriousness underneath. These weren’t just stunts. They were large-scale, well-funded, long-term operations involving real scientists, real pilots, and real geopolitical stakes. The fact that they didn’t work doesn’t make them foolish, it makes them experimental. Science is full of ideas that sound brilliant until they meet reality. The difference here is that the experiments were conducted in the atmosphere, over foreign nations, during wartime. You don’t get much higher stakes than that.

Today, the planes are grounded. The cloud seeding missions have stopped. The 54th Squadron doesn’t fly anymore, and the P-3s that once braved the eyewalls of hurricanes are mostly retired, sitting on tarmacs like old warhorses. The data lives on, used in modern forecasting and climate research. The treaties remain, a legal barrier against turning the weather into a weapon, though as climate change accelerates and geoengineering becomes more tempting, one wonders how long that barrier will hold.

The slogans still echo, in their way. “Make mud, not war” is either a masterpiece of bureaucratic dark humor or a confession of moral evasion. Project Storm Fury sounds like a rejected Marvel villain, but it was real. And somewhere, in a dusty archive, there’s a flight log from 1971 that reads: “Dropped silver iodide over Trail Segment 4. Rain commenced 18 minutes later. Enemy movement halted. Mission success.” Followed, one assumes, by someone in a flight suit saying, “Well. We basically invented rain warfare,” and then immediately being told to never speak of it again.

Comments

Post a Comment