This Astronomer Convinced the World That Martians Built Canals—Then Discovered Something Even Weirder

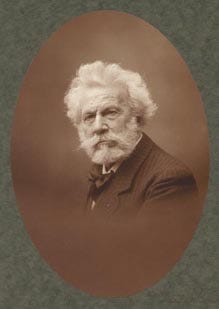

Camille Flammarion was French. The confirmation arrived early, almost as if the wheel of geographical probability had spun and landed squarely on France, which, given the subject, was less a gamble and more a formality. He was born Nicolas Camille Flammarion on 26 February 1842 in Montigny-le-Roi, a small commune nestled in the rolling hills of Haute-Marne, a region more known for its quiet pastoral rhythms than for producing men who would gaze beyond the stars. Yet there, amid the chestnut trees and limestone outcrops of eastern France, a mind was forming that would not be content with horizons bounded by earth. His dual identity, as astronomer and author, was more than a coincidence of talent. It was a convergence of temperament and timing, the fortune of being born into an age when the cosmos was opening like a long-sealed letter, its contents slowly deciphered by the curious, the bold, and the occasionally credulous.

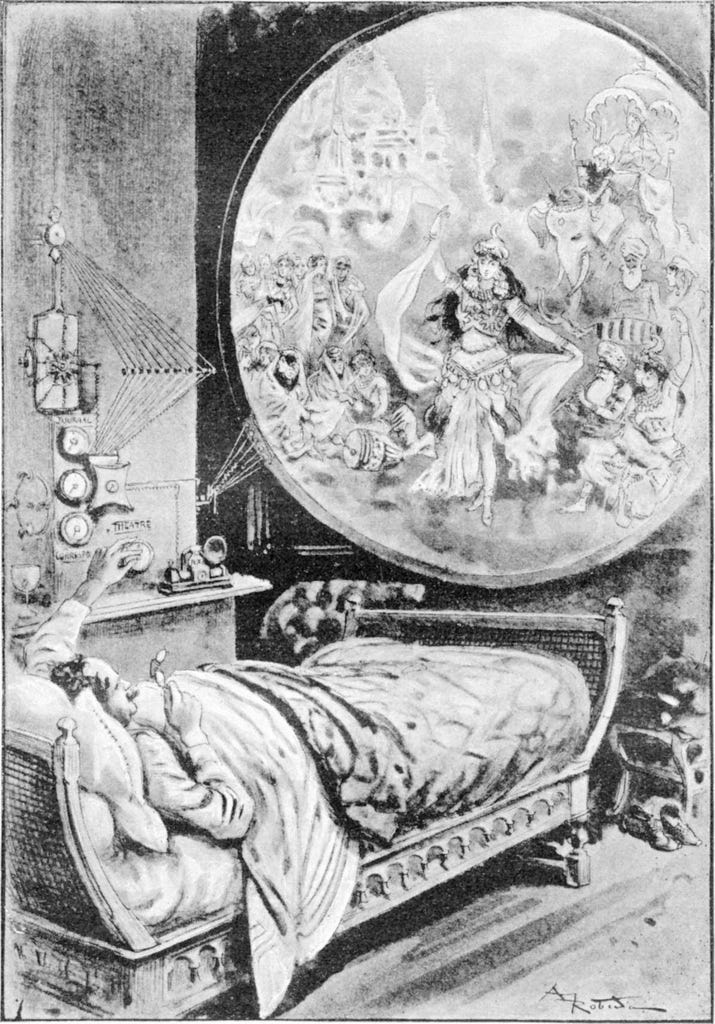

His books straddled the line between fact and fiction so precisely that they occasionally blurred into something else entirely, faction, if such a word were permitted, though it was immediately dismissed as a linguistic abomination before being grudgingly accepted as a legitimate descriptor. Flammarion wrote about the cosmos with the fervor of a scientist and the flair of a novelist, producing works that were at once educational and fantastical, grounded in observation yet unafraid of speculation. He did more than write about astronomy; he wrote through it, using the stars as both canvas and compass, mapping not only celestial bodies but also the contours of human longing. His *Astronomie populaire* (1880), later translated as *Popular Astronomy*, became a bestseller not because it was easy, but because it was alive, its pages thrumming with the excitement of discovery, its prose lit by the glow of distant suns. It was a book that treated the reader not as a passive recipient of facts, but as a fellow traveler on a journey through the infinite.

The distinction between science fiction and popular science was not always clear in his time, and Flammarion operated in the space where the two bled together. He was not a professor, despite the title occasionally being bestowed upon him in reverent tones, nor was he formally affiliated with any major academic institution in the way modern scientists are. His authority came from output, influence, and an insatiable curiosity that refused to be confined by disciplinary borders. He believed in the scientific method, applied it rigorously when he could, and yet remained open to ideas that sat well beyond its usual jurisdiction. This made him both a pioneer and a paradox, a man who demanded evidence while entertaining visions of souls migrating from planet to planet, who championed empirical observation while publishing photographs of levitating tables and faces imprinted in putty.

One of the most persistent astronomical myths of his era was the existence of canals on Mars. Flammarion was among those who entertained the idea that these linear features, visible through early telescopes, were artificial constructions, evidence of an advanced Martian civilization engaged in large-scale irrigation. The notion was not his alone; it gained significant traction thanks to Percival Lowell in the United States, who mapped elaborate networks of Martian canals and speculated about the intelligent beings who must have built them. To modern ears, the idea sounds absurd, conjuring images of little green men puttering along in Martian narrowboats, waving at passing satellites. But at the time, it was a serious hypothesis, discussed in scientific circles and popular media alike. Flammarion, in his 1892 work *La planète Mars et ses conditions d'habitabilité*, treated the canals as real phenomena, interpreting them as the rectification of ancient riverbeds, a desperate engineering effort by a dying race on a desiccating world. He imagined Mars as a planet in its twilight, its oceans long vanished, its atmosphere thinning, its inhabitants, perhaps tall, slender, and wise, struggling to redistribute the last remnants of water across vast arid continents.

The reality, as it turned out, was far less dramatic. The canals were not canals at all. They were not rivers, motorways, or even rain-covered highways glinting under alien sunlight. They were not formations of any kind, natural or artificial. They were, in fact, optical illusions, products of the human eye’s tendency to connect scattered points of light into straight lines, especially when viewed through the imperfect optics of 19th-century telescopes. The brain, eager for pattern and meaning, filled in the gaps. What observers saw was less Mars itself than a projection of their own expectations onto the void. Some suggested that cobwebs on the telescope lens might have contributed, though this was dismissed as overly literal. The true culprit was perception itself, aided by the limitations of instrumentation and the power of suggestion. By the 1920s, better telescopes and more refined observational techniques revealed the truth: no canals, no irrigation grids, no grand Martian civilization, just a barren, cratered world swept by dust storms and painted in shades of rust.

Flammarion, ever the bridge between worlds, stood at the intersection of emerging science and lingering mysticism. His era was one of transition, where astronomy was still untangling itself from astrology, and where the boundaries between the empirical and the esoteric remained porous. Charles Darwin had already reshaped the understanding of life on Earth, providing a naturalistic framework that challenged religious orthodoxy. At the same time, spiritualism was on the rise, a movement that claimed the dead could communicate with the living through mediums, séances, and trance states. Flammarion was fascinated by both. He admired Darwin’s work and aligned himself with the scientific worldview, yet he also devoted considerable energy to investigating the claims of spiritualism, always as a skeptic with an open mind, never as a believer. He had been influenced in his youth by Jean Reynaud’s *Terre et ciel* (1854), a curious synthesis of Christianity and reincarnation that proposed the soul’s journey through successive worlds as a path to enlightenment. This idea, that Earth was but one classroom in a cosmic curriculum, resonated deeply with Flammarion, who came to see humanity not as the center of creation, but as students in an interstellar academy, slowly ascending through reincarnations across the stars.

In 1907, he declared that dwellers on Mars had attempted to communicate with Earth, a statement made with enough seriousness to be recorded but with enough ambiguity to avoid outright ridicule. Around the same time, he turned his attention to a comet, specifically, a seven-tailed comet that had captured public imagination. The image of a comet with seven distinct tails was likely the result of atmospheric distortion or instrumental error, but Flammarion treated it as a genuine phenomenon, weaving it into his broader cosmological speculations. The idea of multiple tails suggested complexity, intention, perhaps even design. To the modern observer, it sounded like someone had looked through a kaleidoscope and mistaken the pattern for reality. YFor Flammarion, anomalies were never to be dismissed; they were to be interrogated, each one a potential clue in the grand mystery of the universe.

Halley’s Comet made its return in 1910, and with it came a wave of public anxiety. For the first time, scientists had spectroscopic data on the composition of a comet’s tail, allowing them to determine its chemical makeup. They found cyanogen, a toxic gas composed of two carbon and two nitrogen atoms, (CN)₂, as it was written, with the brackets emphasizing its molecular structure. Flammarion seized on this information and issued a warning: as Earth passed through the tail of the comet, the atmosphere would become impregnated with poison gas, potentially snuffing out all life on the planet. The phrasing varied in translation, but the sentiment was consistent, doom was imminent.

He was wrong, of course. The concentration of cyanogen was far too low to pose any threat, and the tail’s passage was as harmless as a shadow crossing a field. But the damage was done. Panic, or at least mild disquiet, rippled through parts of the population. Headlines played up the danger with theatrical flair. Sales of gas masks spiked, as did those of wine and, reportedly, life insurance policies. The episode became a case study in how scientific information, when stripped of context and amplified by authority, could trigger irrational behavior. Flammarion, for all his skepticism in other domains, had momentarily abandoned caution in favor of sensationalism. In truth, he had later clarified his position in the *New York Herald*, stating that the poisoning of humanity was “improbable” and that the comet’s matter was too tenuous to affect Earth. He even published a follow-up in February 1910, explicitly denying that he had predicted the end of the world. But the press, ever eager for apocalypse, ignored the retractions and amplified the alarm. The myth outlived the man, as myths often do.

His science fiction works reflected the same duality. *Real and Imaginary Worlds* was one of his most notable titles, a book that explored the possibility of life on other planets, the nature of the universe, and the limits of human knowledge. Even the title was a clue: the real and the imaginary existed as companions, each illuminating the other. He did not dismiss the fantastical out of hand. Instead of accepting claims at face value, he subjected them to scrutiny, asking whether something could be tested rather than simply whether it was true. When it came to psychics and mediums, his approach was unusually rigorous for the time. He attended séances, observed demonstrations, and interviewed practitioners, all while maintaining a critical stance. His investigations led him to Eusapia Palladino, a medium whose performances included table levitations and facial impressions in putty. Flammarion published photographs of these phenomena, believing some to be genuine. But critics, including the skeptical Joseph McCabe, noted that the faces in putty were always Palladino’s own and that her hands were never fully clear of the levitating objects. The evidence, upon closer inspection, looked less like proof of the supernatural and more like clever trickery.

There is a quote attributed to him that captures his attitude perfectly: “It is infinitely to be regretted that we cannot trust the loyalty of mediums. They almost always cheat.” The statement is damning, yet it is not a dismissal. It acknowledges fraud while leaving room for the possibility that something genuine might exist beneath the deception. He rejected the methods of the spiritualists, yet he valued the questions they raised, about consciousness, death, and the possibility of survival, as worth pursuing. What he wanted was not a medium, but a well-controlled experiment. The joke was made that he needed a well done, a rare thing in France, but the underlying point was serious: evidence required rigor, not theatrics.

An anecdote from the early 20th century illustrates the cultural weight of spiritualism. In a mill town in northern England, a spiritualist service was held in a repurposed church, complete with pews, pulpit, and altar. Attendees, mostly older women, gathered for what was effectively a religious ritual centered on communication with the dead. A medium stood at the front, delivering messages in the style of cold reading, vague statements calibrated to elicit recognition from the audience. “I’m getting the vision of someone who worked in a factory,” he said. “Maybe on some kind of cloth machine? They were called Edith.” A murmur of recognition rose from the crowd. Someone’s sister’s friend, from years ago. A tenuous link, stretched to fit.

When the medium failed to land a hit, he adjusted. “Is there a problem with a child?” No. “No? The readings are very fuzzy from the other side.” Then, with seamless pivot: “Is there a problem with children or young people at all?” Still no. “It’s for the future.” The audience accepted this. The logic was circular, the predictions unfalsifiable, the technique transparent to anyone watching closely. Hymns were sung at the end. Orange squash was served. Attendees wobbled out, some stopping for a samosa butty, a deep-fried pastry filled with spiced meat, served in a bread roll, often with mint sauce, on the way home. The Empire had reached the north, and with it, a peculiar blend of devotion, desperation, and snack food.

Flammarion occupied a unique position in this landscape. He was not a charlatan, nor was he a true believer. He was a seeker, one who applied the tools of science to questions that science had not yet answered. He wanted proof, but he also wanted wonder. He entertained the idea of Martians, not on the strength of evidence, but because the universe was vast and silence alone could never prove emptiness. Similarly, he allowed for the possibility of life after death, not due to ghostly encounters, but because the mind remained one of the last uncharted territories. His skepticism was not a wall, but a filter.

His influence extended beyond his writings, It was in Juvisy-sur-Orge, where he died in 1925 at the age of 83, peacefully, one assumes, though perhaps mid-argument with a medium or a meteorologist, that Flammarion spent his later years cultivating both celestial observations and metaphysical curiosities. He had built a private observatory there, a modest structure that looked less like a temple of science and more like a garden shed that had overreached its station. Yet within its walls, the cosmos was dissected with equal parts rigor and reverie. It was here, beneath a roof that occasionally leaked during meteor showers (a poetic inconvenience, if not a symbolic one), that he published L’Astronomie, the journal he founded in 1882. The magazine did not merely report on the stars; it speculated, pontificated, and occasionally gasped in astonishment at its own conclusions. In 1895, it absorbed the Bulletin de la Société astronomique de France, the journal of the organization he had founded and led as its first president. The merger was officially about administrative efficiency, but privately, it was seen as Flammarion quietly annexing the entire French-speaking astronomical community under the banner of his personal newsletter.

His literary output was staggering, over fifty titles, ranging from rigorous observational summaries to novels in which souls zipped across galaxies faster than light, pausing only to deliver philosophical monologues to startled shepherds. His 1862 debut, The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds, was bold, brash, and suspiciously well-timed: he was dismissed from the Paris Observatory that same year. Whether the two events were causally linked remains a mystery, though one suspects the directors grew weary of a man who, while meant to be calculating orbital trajectories, was instead sketching diagrams of Martian irrigation systems in the margins of his notebooks. The book argued that every planet was a kind of cosmic boarding school for the soul, a concept inspired by Jean Reynaud’s Terre et ciel, which blended Christianity, reincarnation, and a faintly Gallic impatience with linear existence. Flammarion took this idea and expanded it, across planets, through time and space, and into several editions of his bibliography.

Several asteroids were named in his honor, including one after his sister, another after his niece, and possibly one after his first wife. These namings were never acts of self-promotion; they came from the astronomical community itself, acknowledgments of his contributions to the field. His name also appears on Mars, etched into craters rather than traced as canals. The Martian surface is pockmarked with them, silent testaments to impacts both ancient and violent. To name a crater after Flammarion was fitting. He had spent his life looking at Mars, imagining its inhabitants, speculating about its secrets. Now, in a sense, he was there, his name etched into the very landscape he had studied from afar.

The idea of Martians living in canal boats, pootling along at four miles per Mars hour, remained a joke, but it was a joke with a kernel of historical truth. People had believed, however briefly, that Mars was inhabited, that its surface was shaped by intelligent design, that communication across space was possible. Flammarion had neither started nor ended that belief, but he had participated in it, shaped it, and, in moments, amplified it. He had also, in his more sober moments, questioned it. He had demanded evidence. He had called out fraud. He had insisted on method. And yet, when the data was inconclusive, he allowed himself to hope.

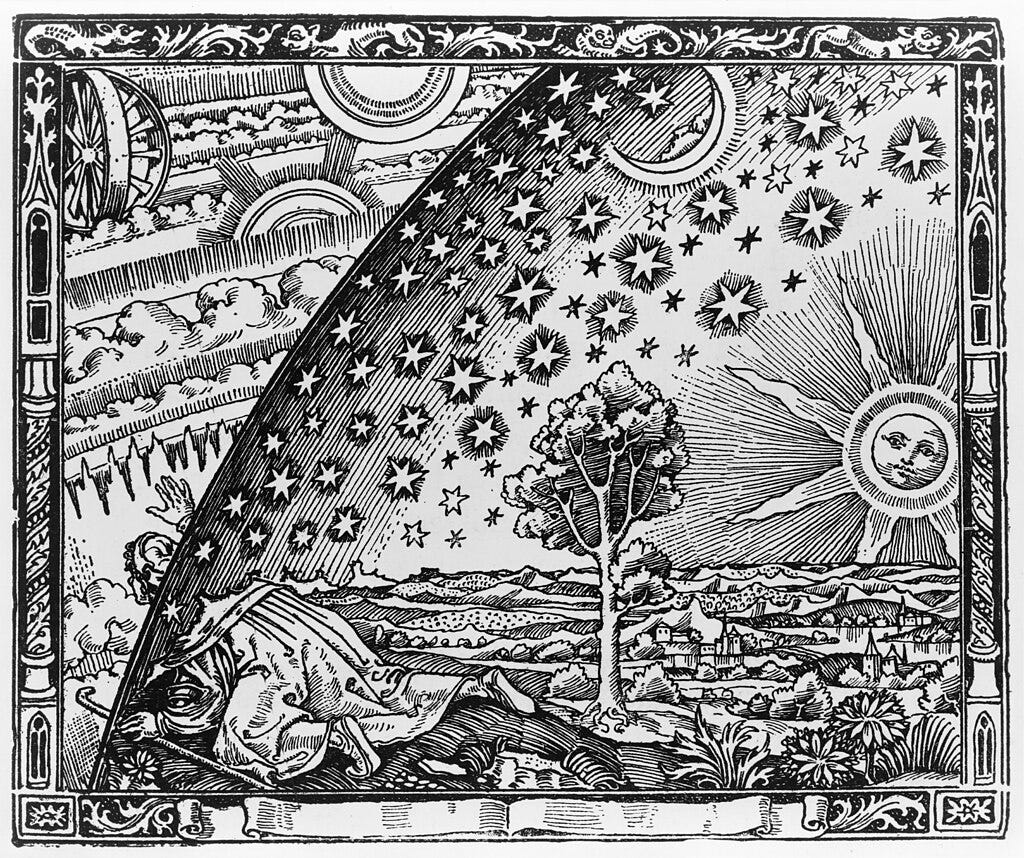

He was not alone in this. The tension between what could be known and what might be true defined an entire era of scientific exploration. Astronomy was expanding rapidly, revealing a universe far larger and stranger than previously imagined. At the same time, the tools for understanding it were still primitive. Telescopes were limited, theories were incomplete, and the line between observation and interpretation was easily crossed. In that gap, speculation flourished. Flammarion stood in the gap, sometimes peering through the lens, sometimes writing the story that the lens seemed to suggest.

His legacy is not one of definitive discovery, but of inquiry. He did not prove the existence of Martian civilizations or life after death. He did not invent a new branch of science or overturn an old one. What he did was maintain a stance, curious, critical, open, that allowed him to engage with ideas at the edge of knowledge without falling off. He was wrong about the comet, mistaken about the canals, and overly credulous at times about the possibility of interplanetary communication. But he was also right about the importance of asking questions, of testing claims, of not dismissing the strange simply because it did not fit the current model.

The craters on Mars bear his name. The asteroids carry the names of his family. The books remain in print, read by those interested in the history of astronomy, the evolution of science fiction, or the peculiar mindset of a man who could believe in both data and destiny. He wanted the universe to feel populated, with stars, planets, minds, stories, and connections. He did not find proof, but he did not stop looking. And in that, perhaps, lies the most enduring truth of all.

Comments

Post a Comment