The Dead Man’s Switch That Didn’t Stop a Runaway Train

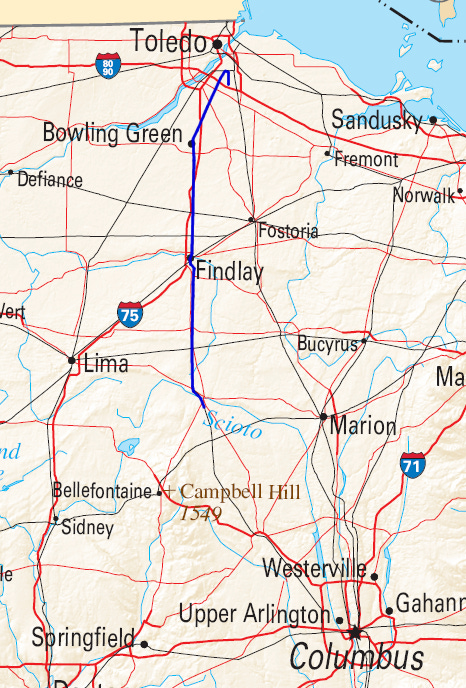

The Crazy Eights incident, officially known as the CSX 8888 incident, is a rare case in modern rail history where a freight train went completely out of control, without any fatalities, without any major damage to infrastructure, and without even being particularly dangerous. It’s an event so unremarkable in its actual outcome that Hollywood felt compelled to turn it into a dramatic thriller, complete with a high-speed chase through a fictional city called Stanton, a devilish bend in the tracks, and a cast of heroic engineers racing against time to stop a runaway locomotive before it plowed into populated areas. The film *Unstoppable*, starring Denzel Washington and Chris Pine, is based on this real-life occurrence, but it takes enormous liberties with the facts. In reality, the train wasn’t hurtling toward a catastrophe; it was simply rolling down a long stretch of track, unattended, for over two hours, 66 miles of flat, rural Ohio terrain, from Walbridge to just southeast of Kenton, while its namesake locomotive, an aging but still-formidable EMD SD40-2, chugged along at a steady 52 mph, hauling 47 cars loaded with everything from empty boxcars to two tankers brimming with molten phenol, a caustic industrial compound that eats through skin and demands careful handling but, fortunately, doesn’t ignite with the slightest spark like gasoline. The irony, of course, is that the most hazardous substance aboard posed little risk of explosion, only chemical burns, and even those required direct contact, which no one got.

The incident began at a classification yard, a place where freight cars are sorted, reassembled, and prepared for onward journeys. These yards are complex networks of tracks, switches, and signals, often involving gravity-assisted shunting. One type of yard, known as a hump yard, uses a small hill: wagons are pushed over the crest and roll down by gravity, guided by switches and brakes into the correct outbound trains. But CSX 8888 wasn’t in such a yard. It was in Stanley Yard, CSX’s primary flat yard for the Toledo region, a sprawling, low-rise labyrinth of parallel tracks where locomotives inch forward and backward like ants rearranging crumbs, a place built for methodical labor, not momentum. Flat yards rely entirely on human finesse and diesel torque, not gravity, and in that context, the accident didn’t stem from physics gone wrong, it stemmed from human error, mechanical failure, and a chain of misjudgments that allowed a powerful diesel locomotive to break free. That locomotive, originally delivered to Conrail in August 1977 as unit #6410, had spent most of its life in quiet anonymity, hauling coal and manifest freights across the Rust Belt, until the 1999 division of Conrail rebranded it as CSX #8888, a number so serendipitously ominous it would earn the nickname *Crazy Eights* among railfans and dispatchers alike. By 2001, it wore the faded yellow-and-blue “Bright Future” YN2 livery, its primer showing at the coupler pockets and cab corners, a veteran still pulling its weight but already past its prime, a machine that had seen three decades of rain, snow, heat, and diesel exhaust, and would yet see far more.

The sequence of events started when the engineer, a 35-year veteran whose name CSX has never released, noticed that one of the points, the switch controlling which track the train would take, was misaligned. He had just completed a routine shunting operation and was preparing to move the train onto track D10 for departure on an outbound freight. Instead of stopping or reporting the issue, he decided to fix it himself. He got off the locomotive and used a large hammer to physically adjust the switch. That decision would prove catastrophic, not because of recklessness alone (yard crews perform this maneuver routinely). The real cause lay in the surrounding conditions, which converged into a perfect storm of procedural gaps. The tracks were slick from recent rain, which reduced braking effectiveness and gave the train an imperceptible forward creep once the independent air brake, applied only to the locomotive, not the full train, began to fade. He had, in his haste, skipped re-engaging the automatic air brake system, a step normally reserved for mainline runs but functionally vital here. In yards, air brakes are often disabled to allow easier movement between tracks, and they’re not automatically reconnected unless the engine is set for mainline service; the practice is routine, almost reflexive, and precisely why it’s so treacherous when routine becomes complacency. So while the engineer managed to activate the locomotive’s independent brake, it didn’t work because the system wasn’t fully armed. He then tried to use the dynamic brake, but that required a ballet of controls few outside the cab truly appreciate: the dynamic brake handle, three-position, *off*, *set-up*, *brake*, had to be moved to *brake* while the throttle was simultaneously reset to *notch 0*. Instead, he left the throttle in *notch 8* and failed to complete the dynamic brake selection. The result? This was acceleration, not deceleration. In an EMD SD40-2 of that era, the dynamic brake system doesn’t override the throttle, it *shares* the traction motors. So if the throttle is left in power while the dynamic brake lever is only halfway engaged, the motors receive conflicting instructions: generate power *and* absorb momentum. The result, as any veteran engineer could tell you over coffee in a crew lounge, is that the locomotive interprets the ambiguity as *full power ahead*. And so it did.

The train surged forward, gaining momentum, and within seconds, the engineer, realizing his error too late, leapt after it, scrambling onto the walkway only to be dragged 80 feet before letting go, scraping his arms and knees in the gravel beside the rails. By then, the dead man’s switch had already tripped. The safety feature designed to cut fuel and apply brakes when the operator left the cab failed simply because there was nothing for it to act upon. With the train’s air brakes disconnected and the independent brake already fading, the emergency signal went unanswered. The locomotive rolled out of Stanley Yard and onto the Toledo Line Subdivision, an expanse of single-track, gently graded mainline built in the early 20th century for steady, unspectacular freight service. It was designed for workhorse reliability rather than high drama. And for the next 115 minutes, unit #8888 delivered exactly that: reliability. It didn’t stall. It didn’t overheat. It didn’t derail on poorly maintained curves. It simply kept going, mile after mile, through farmland and small towns, Pemberville, Woodville, Arcadia, its horn silent, its cab empty, its engineer side window left slightly ajar, flapping in the wind like a dog’s ear on an open car window.

Once the train was free, there was no way to stop it. The engine had full fuel capacity, roughly 4,000 gallons of diesel, and it was running efficiently, its 3,000-horsepower 16-645E3 prime mover humming along at 900 rpm, cool and steady. The only thing keeping it from going faster was aerodynamic drag and friction; even the brake shoes, applied the entire time but disconnected from the train’s reservoirs, eventually wore down to metal-on-steel, glowing cherry-red in places before burning completely off, leaving the locomotive essentially brakeless on its final miles. The crew could have tried to disconnect the locomotive from the rest of the train, but the train was fully coupled with standard AAR Type E knuckle couplers, and the coupling mechanism was not designed for rapid disengagement, especially not from the *rear* of a moving consist. There were no emergency stops programmed into the system; in 2001, positive train control (PTC) was still a distant dream, and remote kill switches were largely restricted to passenger or high-hazard routes. The train had no automatic braking mechanism once it left the yard. It simply kept going. And because it was a single-track section, it couldn’t be rerouted without halting all north-south traffic in northwest Ohio. The nearest signal box was miles away, and by the time Stanley Yard dispatch realized something was wrong, when a radio call went unanswered and the train passed its clearance window, the runaway was already well beyond recovery by conventional means.

Meanwhile, the railroad authorities scrambled to respond. They considered several options. The first was a portable derailer, a heavy, wedge-shaped steel device clamped to the rails to guide wheels off the track at low speed. If successful, the train would derail, lose traction, and come to a stop due to friction. But the problem was timing, and physics. Portable derailers are rated for speeds up to 10 mph; #8888 was doing over 50. When the first attempt was made near Woodville, the derailer didn’t deflect the wheels, it was *shattered*, torn clean off the rails by the locomotive’s rigid frame and sheer inertia. Undeterred, local police tried a more cinematic tactic: sharpshooting the red emergency fuel cutoff button on the cab wall, a move straight out of a Western. Three rounds struck the locomotive, but missed the small, recessed button and instead punctured the nearby red fuel cap, leaking diesel onto the ballast. Even if they’d hit the button, it likely wouldn’t have worked: former Conrail SD40-2s like #8888 required the button to be held for *several seconds* to activate, not a momentary tap. A bullet strike, even a direct one, wouldn’t sustain contact long enough. Diesel fuel, meanwhile, refused to play along; it pooled, soaked into the ties, and evaporated, but did not ignite. Diesel, unlike gasoline, has a flash point of over 125°F and won’t combust without sustained heat and compression. So the idea of setting it on fire was not just impractical, it was physically implausible.

Eventually, the solution came not from force, but from cooperation, the kind of quiet, competent improvisation that defines real-world railroading far more than Hollywood ever admits. Jess Knowlton, a 31-year veteran engineer nearing retirement, and Terry L. Forson, a conductor with just one year’s experience, were running northbound train Q636-15 when dispatch called with the impossible request: *uncouple your locomotive, turn around, and chase a runaway.* They complied without hesitation. Backing onto the mainline, they took CSX #8392, an SD40-2 sister to #8888, and began pursuit. Up ahead, a second unit, GP40-2 #6008, was prepped to intercept from the front if needed, a contingency plan that thankfully went unused. Knowlton and Forson, coordinating with dispatch over crackling radio, matched speed carefully, too fast, and they’d overshoot; too slow, and they’d fall behind. When they drew within coupling distance, Knowlton brought #8392 alongside the last car, gently nudged the coupler, and heard the sweet, metallic *clunk* of connection. Then came the real work: engaging their own dynamic brakes to modulate rather than to stop. By bleeding speed incrementally, they brought the runaway from 52 mph down to 12 mph over nearly 20 miles, a process requiring constant vigilance, smooth control inputs, and nerves of tempered steel. At that speed, trainmaster Jon Hosfeld, cool, deliberate, and utterly unflappable, stepped off the embankment, broke into a jog alongside the swaying cars, and hoisted himself into the rear vestibule. From there, he walked forward through the empty train, climbed into the cab of #8888, and shut down the prime mover with a single twist of the master key. The locomotive exhaled, a long, hissing sigh of air tanks depressurizing, and coasted to rest at the Ohio State Route 31 crossing, just southeast of Kenton. No explosions. No flipped tank cars. No last-second dive onto a moving ladder. Just a man in a high-visibility vest walking up to a stopped train and turning off the key.

As for the original engineer who caused the incident, his fate remains largely unknown, not due to secrecy, but corporate discretion. CSX never confirmed disciplinary action, a decision consistent with a “just culture” approach to safety, one that focuses on learning from errors rather than assigning blame. In aviation and rail industries, accountability is often structured around systemic failures, not individual fault. If people fear punishment for honest mistakes, they’re less likely to report them, which undermines safety. So the focus shifts to improving procedures, training, and technology. In this case, the root cause was clear: the engineer failed to secure the train properly, but the system allowed him to disconnect the brakes and leave the cab without triggering an automatic stop. Had the dead man’s switch been hardwired to dump the entire brake pipe, or had yard protocols required a formal “shut-down checklist” before dismounting, the accident might have been avoided. But instead, the system relied on human vigilance, a fragile safeguard, especially after 35 years on the job, especially on a damp Tuesday afternoon in May.

After the incident, the locomotive was recovered and returned to service, not scrapped, not enshrined, but *rehabilitated*, in the fullest sense of the word. It spent the next several years quietly working local turns, Monroe, North Carolina, in 2008; Corbin, Kentucky, where it suffered a prime mover failure in 2009 and sat idle for four years during the post-2008 economic slump. By 2013, rumors swirled it would be dismantled at Huntington Shops, its number boards already pilfered by souvenir hunters. Yet CSX had other plans. In August 2015, it rolled westward, past East St. Louis, through Pocatello, Idaho, en route to MotivePower Industries in Boise, where it would undergo conversion into an SD40-3: a modernized rebuild with a new cab, upgraded electronics, and a fresh coat of paint. The transformation was completed in early 2016. Its new number? #4389. A clean slate. A second life. And though railfans still refer to it as *Crazy Eights*, the locomotive itself carries no outward trace of its past, no plaque, no asterisk in the roster, no cautionary tale etched into its frame. It simply runs, as it always has, moving freight across America, anonymous once more.

Yet even in anonymity, #4389 can’t quite escape its legacy, at least not among those who remember the rhythm of its old prime mover or the way its cab smelled of decades of diesel fumes and stale coffee. In railfan circles, sightings are still logged with quiet reverence, like spotting a ghost that’s learned to keep its head down. When it passed through East Syracuse in 2018, freshly rebuilt and gleaming in CSX’s current blue-and-gray livery, someone snapped a photo. On the surface, it looked like any other SD40-3, yet he recognized the frame, the truck configuration, the subtle kink in the long-hood walkway where a weld had been repaired after a minor yard collision in the late ’90s. The marks of a legend are written in its scars, not its number.

The rebuild itself was no cosmetic touch-up. At MotivePower in Boise, the same facility that breathes new life into dozens of aging EMDs each year, #8888 was stripped to its bare chassis. Its original 16-645E3 engine, worn smooth by thirty years of torque cycles and a final, infamous 66-mile sprint, was scrapped. In its place went a remanufactured 16-645F3B, rated for cleaner emissions and slightly higher reliability, though still unmistakably EMD in tone and temperament. The cab, once cramped, analog, and lined with decades of handwritten notes and coffee-ring stains, was replaced with a modern wide-nose design, HVAC included, compliant with current FRA crashworthiness standards. Gone was the old control stand with its three-position dynamic brake lever, the very interface that had tripped up the veteran engineer on that damp May afternoon. Its replacement uses a microprocessor-assisted throttle with built-in conflict detection: try to leave the throttle in power while selecting dynamic brake, and the system won’t just ignore you, it’ll warn you, flashing an amber light and emitting a low chime, like a car reminding you the doors are open.

Some purists grumble that the rebuild erased history. But the truth is more nuanced. The original 8888 was never preserved. CSX avoided doing so not out of shame or secrecy, but because preservation carries a hint of reverence, and this locomotive was no hero. It was a participant. A tool that did exactly what it was told, right up until the moment it was told something contradictory. Railroads don’t enshrine contradictions; they resolve them. And so #8888 was resolved, into something safer, more efficient, more predictable. Its phenol-laden run in 2001 directly contributed to revised CSX yard protocols: mandatory two-person verification before brake disconnection, revised switch-alignment checklists, and, critically, the retrofitting of dead man’s switches on older SD40-2s to independently dump the brake pipe, even if automatic brakes were nominally “off.” It wasn’t a recall; it was a reckoning, one locomotive at a time.

Ironically, the very tank cars it hauled that day, those two carrying molten phenol, were later rerouted permanently away from single-track subdivisions during high-risk operations. The panic over phenol had little to do with its volatility, it isn’t especially so, and everything to do with perception, which matters as much as physics when a train barrels past farmhouses and grade crossings. A chemical spill, even non-flammable, triggers hazmat evacuations, media helicopters, and congressional inquiries. CSX learned that day that containment isn’t just about gaskets and valves; it’s about narrative control. Hence, no press conferences, no naming of the engineer, no courtroom drama, just a quiet internal review, updated training modules, and, eventually, a locomotive quietly slipping west on a manifest freight, destined for rebirth.

Even the graffiti inside the old cab, “If you’re reading this…”, didn’t survive the rebuild. The wall it was scrawled on was cut out and replaced. Somewhere, in a drawer at Huntington Shops or tucked into a retired engineer’s logbook, a rubbed pencil tracing might still exist: a palimpsest of warning, preserved in memory rather than in steel. The story lives on, not in a museum, but in the minds of those who study rail safety, and in the marginalia of engineers’ logbooks, where someone, sometime in 2008, scrawled inside the cab of #8888: *“If you’re reading this, you’re probably about to make the same mistake.”* It’s worth noting that the incident didn’t just highlight flaws in procedure, it exposed a deeper issue in how safety systems are designed. The locomotive was equipped with multiple braking mechanisms, air brakes, dynamic brakes, and a dead man’s switch, but none were coordinated to work together in an emergency scenario. In fact, the very design of yard operations prioritized efficiency over fail-safes. Disconnecting air brakes for shunting was standard practice, and engineers were trained to re-engage them before departure. But the system assumed compliance, not failure. When the engineer left the cab, he triggered the dead man’s switch, which should have applied the brake. But because the air brake was disconnected, the signal did nothing. It was a cascade of assumptions: that the switch would be properly aligned, that the brake system would be active, that the driver wouldn’t leave without securing the train. Each assumption failed. And while the outcome was fortunate, no injuries, no derailment, the near-miss underscores how fragile rail safety can be when technology and human judgment don’t align.

It’s a reminder that even the most mundane events can become legendary when filtered through the lens of fiction. And sometimes, the most boring accidents make the best movies, especially when the real version involves rain-slicked ballast, misunderstood control levers, and a veteran engineer jogging alongside a freight train at 12 mph, not leaping from helicopters or dodging collapsing bridges. The truth is quieter. It’s slower. It smells like diesel and damp gravel. And in the end, what impresses most is the fact that it was possible at all.

Comments

Post a Comment