The Surprising History of Australia's "Big Things" Tradition

The Big Lobster sounds like the name of a New Orleans gangland boss, gravel-voiced, menacing, probably wearing a seersucker suit and cracking walnuts with his bare hands. It comes close to a Spinal Tap moment, no one ordered a hundred-foot lobster by mistaking inches for feet, yet the spirit of the mix-up lingers.” Then again, maybe the restaurant is just a front, for the real boss, a gigantic, man-sized lobster lurking behind the kitchen door, claws clicking rhythmically like castanets as it eyes the door. A lobster bigger than a man. A lobster the size of a bear. The sort of creature that would’ve stomped across Tokyo decades ago, smashing skyscrapers, toppling transmission towers, before quietly vanishing into the sea, leaving only grainy newsreel footage and a single claw tip embedded in the side of a department store. Someone, somewhere, would’ve filmed it in a bulky rubber suit, stomping awkwardly through miniature cityscapes while extras scattered in terror, arms flailing, mouths open in silent, black-and-white screams. Everyone in the studio giving it their all. “All these lobsters comin’ in here, givin’ it that.”

It may not be an actual, alive lobster. That’s the first assumption, the sobering reality check: no pulsing antennae, no saline tang in the air, no nervous twitch of the tail fan as it scans for threats. Instead, it’s the kind of monument you find in certain parts of the world, those enormous, slightly melancholic fibreglass tributes to local industry or historical quirks. The sort of thing erected by towns hoping desperately to draw tourists off the highway, to be immortalised on a postcard next to a petrol station and a pie van. There’s one in America, for instance: a colossal ear of corn looming over some Midwestern crossroads, celebrating the fact that, yes, once upon a time, corn grew here. But this one isn’t in America. It’s not in the Tyrol of Austria, either, though the idea of a lobster perched halfway up an alpine slope is undeniably compelling. “Why have you got this lobster?” a hiker might ask, panting, hands on knees. And the local, wiping sweat from his brow with a lederhosen-clad forearm, replies in an accent that belongs nowhere on Earth: “We stole it from Australia.” He then gestures solemnly toward the crustacean and adds, “He teaches them the folly of their ways, Hansel. From its claws… will come fondue.” And maybe, just maybe, if you listen closely, a tiny cuckoo clock emerges from its mouth on the hour, *cuckoo! cuckoo!*, right as slime drips down the wall behind it in perfect sync with the *Alien* soundtrack. Three o’clock, everybody. Mr. Jones is late for his 2:30 appointment. Thank you, Miss Smith.

This isn’t steampunk Siri, though that’s a tempting diversion, a mechanical butler whose activation switch is, regrettably, located in an awkward place, causing unintended service calls in trouser pockets across the land. Different voices available: generic man, generic woman, but only within city limits. Venture beyond the urban fringe and he simply powers down mid-sentence, leaving you stranded on a country road, tea request unfulfilled, existential dread rising. Dee-deet. Doo-doot. Walks off.

Back to the lobster. It has a name. Not Rudy. Not Lobby McLob-lob, though that’s closer. The correct answer begins with an L. Larry. Larry the Lobster. A name so obvious, so perfect, it feels inevitable, like it was carved into the fibreglass before the first coat of paint had even dried. In Australia, of course, they might have gone with LOBBO, delivered in a thick, sun-baked drawl, accompanied by the clink of Castlemaine XXXX bottles and the distant roar of fast bowlers threatening Queensland. “Queensland, you’re for it!” The lobster itself, situated in Kingston SE, stands eighteen metres high and weighs four tonnes. It’s not standing upright on its legs, nor is it balanced on its tail like some avant-garde circus act. No, it was originally meant to *rear up*, horse-style, claws raised menacingly over the township, until the local council intervened. There’s a certain logic to this. Planning applications must be reviewed carefully: shed extension, double garage, giant lobster. “Now, we like what you’ve done with the giant lobster,” the officer might have said, leafing through blueprints with a furrowed brow. “We’re not saying that’s a bad idea. What we don’t like is having it rearing up over the whole township. We’ve all seen *Godzilla*. What if it goes wrong? We’re known as a sunshiny country. What if somebody visits, stands in the shadow of the lobster, has a panic attack, and cancels their holiday? Tourism industry’s over. We’re going to have to lie your lobster down, mate.” Though, in fairness, he did raise the possibility of using the shadow to keep tinnies cool.

There’s a local legend about why Larry turned out quite so colossal. It falls just short of a Spinal Tap scenario, no one ordered a hundred-foot lobster by mistake, believing the measurements were in inches, but the resemblance is uncomfortably close. The measurements were drawn up in feet, then misread as metres. Someone shows up with a lorry full of fibreglass and steel, shrugs, and says, “Oh, s***, mate, how big did you want it?” Suddenly, northwest Australia has no baths, every last sheet of fibreglass diverted to this glorious, absurd project. “Strewth, I dunno,” someone mutters, surveying the finished beast. “Keeping tinnies cool underneath its rearing body?” Maybe. The truth, as ever, is slightly less cinematic but no less charming: Larry was designed by Paul Kelly, the same Paul Kelly who’d earlier sculpted *The Big Scotsman* in North Adelaide, that towering kilted sentinel guarding a motel like some Highland sentry who’d taken a wrong turn at Port Augusta and decided to stay. Kelly built Larry in a warehouse in Edwardstown, South Australia, after first purchasing a real lobster, having it stuffed, and using it as a model. He carved the details into foam before laminating over steel armature with fibreglass, six months of work, give or take a few tea breaks and arguments about claw curvature. Only then was it dismantled, loaded onto a flatbed, and driven, slowly, respectfully, down to Kingston SE, where it was reassembled and unveiled on 15 December 1979 by the South Australian Premier David Tonkin, who presumably gave it a pat on the carapace and muttered something about exports.

And let’s not forget the *why* of Larry. This wasn’t whimsy alone. The lobster was commissioned by Ian Backler, a local crayfisherman, note the terminology: here, it’s *cray*, not *lobster*, though Larry wears the title with pride, who’d been struck by inspiration (or indigestion) while touring the United States, where oversized roadside enticements were already a thriving art form. Back home, he partnered with Rob Moyse, engaged architect Ian Hannaford to design the surrounding complex, a restaurant, a theatrette, a gift shop, and set about turning vacant land into a destination. For fifteen years, they ran it themselves, weathering tourist tides and off-season quiet, before selling in 1984. A succession of keepers followed, the Peltzes in 1990, then, after six years languishing on the market like unclaimed luggage at a regional airport, Jenna Lawrie and Casey Sharpe in 2007, who steam-cleaned Larry, repainted him (naturally), and began plotting expansions: wine tasting, tourist accreditation, even accommodation. In 2016, the radio duo Hamish and Andy, no strangers to absurd philanthropy, launched the #PinchAMate campaign to crowdfund Larry’s restoration after years of coastal weathering. The lobster, thus revived, now presides over a leaner, savvier venue: open-plan dining, regional vintages on tap, and no small amount of local pride. One imagines the cray boats still heading out predawn, their crews glancing shoreward as they pass the breakwater, there he is, still upright, still enormous, still *theirs*.

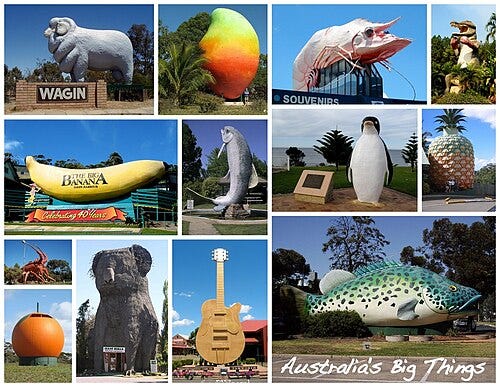

Australia, of course, is dotted with these oversized homages, serving less as clutter and more as punctuation marks across the landscape. Platypus. Tin of beer. Crab, specifically, a big mud crab in Cardwell, lurking like a crustacean sphinx beside the Bruce Highway. There’s even a Big Pie, mounted atop a ten-metre pole beside the car park of a drive-through pie shop. A concept so brilliantly, devastatingly Australian that it demands immediate international replication. Imagine pulling up, window down, ordering a steak-and-kidney, and receiving it through the air like some medieval siege negotiation, only instead of rocks, it’s pastry-wrapped gravy. Try eating that in a car. Hot beef sandwiches, too, dripping, precarious, fundamentally hostile to formalwear and professionalism. In Louisiana, they’ve solved the beverage dilemma with drive-through daiquiri stalls: two-pint cups, straws pre-inserted but hole sealed with sellotape, rendering consumption legally impossible without first committing a minor act of vandalism. Australia goes further: drive-through liquor stores. Pull in, state your preference, XXXX, VB, Carlton Draught, and watch as crates are loaded directly into your boot. Payment accepted. Exit stage left. This is why other countries aren’t trusted with such innovations. They’d abuse them. Though, to be fair, the abuse is already happening, just without the convenience of remaining seated.

At the Bathurst 24 Hours, the unofficial beer allowance was once twenty-four tinnies per person, one per hour, like some alcoholic version of the liturgical hours. There was an outcry when organisers tried to cap it. *Just twenty-four?* In fairness, some manage one tin per half-hour. Though maintaining that pace across a full day, particularly while driving, presents certain logistical and legal challenges. Pit crew members, perhaps, are more lenient, handing over fresh tyres with the same weary resignation as a bartender sliding another round across the bar. *Rack off*, he cried.

Other big things dot the landscape: the Big Wickets in Westbury, looming over the local cricket pitch like the remnants of some ancient, sports-obsessed civilisation. Somewhere, thanks to an unreported nuclear mishap, a gigantic Fred Trueman may already be practising his run-up, preparing to bowl at those wickets with Godzilla-level intensity. Repatriate Giant Trueman! Picture him climbing the Media Centre at Lord’s, Jonathan Agnew clutched in one massive fist, roaring as helicopters circle overhead. King Kong, but with a run-up and a bouncer.

There’s the Big Koala, actually, two of them: the Big Koala and the Giant Koala, differentiated by subtleties lost on the casual observer (one blinks, perhaps, or has better posture). The Kookaburra, too: four and a half metres tall, eyes lit from within, squawking on the hour with that signature grating laugh, the very sound Hollywood used for jungle monkeys before anyone bothered to learn what monkeys actually sounded like. The kookaburra, off-camera, lighting a cigarette between takes, muttering about RADA and union contracts while a man in a monkey suit sips tea nearby, protected by stronger representation. The Monkey Film Union saw to that.

Then there’s the Big Pineapple, a personal favourite, which is, predictably, a big pineapple. Though “predictable” undersells it. The Big Pineapple isn’t just *a* pineapple; it is *the* pineapple, sixteen metres of fibreglass verisimilitude, textured, bronzed, riveted together like segmented armour, standing sentinel on Nambour Connection Road just west of the Bruce Highway near Woombye. It opened on 15 August 1971, a full eight years before Larry clawed his way into existence, making it one of Queensland’s, and arguably Australia’s, first true *Big Things*, in the formal, folk-art sense of the term. Conceived by Bill and Lyn Taylor, returned expats, he a former UN development finance chief, she a New York interior designer, the plantation began as a 23-hectare pineapple farm bought from Gordon Ollett, then transformed into *Sunshine Plantation*, an agri-tourism pioneer that didn’t just *display* fruit but *grew* it, *processed* it, *fed* it to you in a thatched Polynesian restaurant while you waited for the Nutmobile to trundle past.

The pineapple itself could be entered. Inside, a curved steel staircase spiralled upward past hand-painted dioramas of cane trains and canneries, Golden Circle cordial bottles gleaming under Perspex, model trucks hauling invisible loads. The ceiling of the first floor was lined with fibre-cement painted to mimic pineapple flesh, golden-yellow, fibrous, slightly unsettling in its accuracy. Above, the viewing platform wrapped around the steel stalk, offering vistas over rows of actual pineapples, an animal nursery, and a lagoon where wildfowl drifted with the indifference of tenured academics. The train ride, still the record-holder for Queensland’s steepest incline and sharpest passenger-line bend, chugged past ginger, avocados, coffee bushes, and bananas. The narration came not from a recording, but from guides who could tell a Smooth Cayenne from a Queen and relished the chance to prove it.

The Taylors were so successful that in 1982 they were invited to replicate the model in Hawaii, and did, launching the *Hawaii Tropical Plantation* in 1984. Back home, expansion continued: Macadamia Nut Factory (1980), Tomorrow’s Harvest hydroponics greenhouse (1988), the 16-metre *Big Macadamia* (1989), affectionately dubbed the *Magic Macadamia*. Even royalty came calling: in 1983, the then-Prince and Princess of Wales, Charles and Diana, rode the train, waved from the platform, and presumably sampled a jam. (One hopes the Polynesian ceiling held.) By 1980, visitation had soared from 250,000 in 1972 to over a million. Tourism had overtaken sugar as Maroochy’s largest industry, no small feat in a shire where, as late as the 1970s, pineapples ranked third behind dairy and cane.

Of course, fate intervened, as it does to all great empires. A fire in 1978 gutted the restaurant and market. A mini-tornado in 1991 tore through Tomorrow’s Harvest. The Bruce Highway bypassed the site in 1990, diverting the steady stream of holidaymakers who’d once pulled in as automatically as they’d stopped for petrol. By 2010, the attraction had gone into receivership and closed. The Nutmobile was sold off in 2011, to Bauple, of all places, that other great bastion of macadamia lore, and Larry, down south, carried on, unblinking, while the Pineapple stood dormant, a fibreglass sphinx in the hinterland.

Its dormancy was hardly idle: under receivership from 2009 and shuttered by October 2010, the site entered a quiet phase, yet even then, its legacy held. In June 2007, Australia Post immortalised it among five national Big Things on a commemorative stamp series, flanked by the Big Banana, Big Golden Guitar, Big Merino, and, fittingly, Larry the Lobster himself, a subtle cross-continental salute. Earlier, in 2006, the National Trust of Queensland had anointed it a state icon, placing it alongside the Great Barrier Reef and the cane toad as something that “won a lasting place in our minds and memories.” The 2004 study Monumental Queensland had already noted it as the most widely recognised Big Thing in the state, “an outdoor cultural object” that helped define regional identity. Its 2009 heritage listing recognised both its form, the riveted fibreglass shell, the steel-stalked viewing platform, the pineapple-flesh-coloured fibre-cement ceiling, and its function as a working farm blended with education, retail, and spectacle. Even during closure, pilgrims came. Selfie-seekers. Retro-merch hunters. Nostalgists recalling school excursions, royal visits, or the faint whir of the Nutmobile. Its endurance wasn’t in operation, but in recognition: the Big Pineapple remained, unmistakably, the Big Pineapple, even when silent.

But resurrection is a recurring motif in agri-tourism. In 2011, a consortium bought the site and began repairs. By 2013, the Big Pineapple Music Festival had launched, Birds of Tokyo headlining, sold-out crowds returning for the music rather than the dioramas. In 2017, Midnight Oil chose the site for their reunion tour; two icons of the ’80s, briefly cohabiting the same hilltop, one made of steel and fibreglass, the other of leather and righteous indignation. A ropes course, *TreeTop Challenge*, Australia’s highest, opened in 2019. And in an act of poetic vandalism-cum-restoration in 2021, a brewery tour patron, allegedly, hot-wired the old sugar cane train, took it for a joyride down its 250-metre stretch, and derailed it. Charged with dangerous operation of a vehicle (yes, *that* is a charge), he was ordered to pay for repairs. The staff, undeterred, replaced 700 sleepers, rebuilt the track, refurbished the locomotive, *Sugar Cane Train No. 4*, painted proudly, and reopened the line in 2024. The train now departs once more, past pineapple rows and rainforest remnants, a looping hymn to resilience.

In the end, the towering visage of The Big Lobster, “Larry,” perched over the road into Kingston SE, is more than a roadside quirk or a tourist selfie-stop. It stands as a testament: to the pride of a fishing town that chose to celebrate its catch by turning it into legend; to the irrepressible Aussie tradition of turning ordinary industry into audacious public sculpture; and to the way we attach meaning to the landscape, by exaggeration and humour as much as by reverence. In a country where nature looms large and isolation is real, monuments like Larry declare: *we are here, we exist, we make something visible from our world*. So when you park beneath those gigantic claws and raise your camera skywards, you’re not just snapping a photo of a big lobster, you’re participating in the story of place, identity, and the very Australian knack for saying: *Yes, we gave it claws and we made it enormous. And we’re proud.*

And somewhere, up north in Woombye, the Big Pineapple nods in silent, fibreglass solidarity, its leaves rustling faintly in the breeze, its train whistling once more, its legacy no longer frozen in the amber of the ’70s, but sprouting new shoots. It is not, strictly speaking, alive. But neither is it dead. It is *agri-tourism*, that strange, fertile hybrid of commerce and charm, of soil and spectacle, and like the best roadside attractions, it understands the sacred truth: if you’re going to make a statement, make it enormous. Make it climbable. Make it cast a shadow large enough to shelter a generation of tinnies, dreams, and slightly sunburnt schoolkids on excursion. Make it *big*.

Comments

Post a Comment