What Happens When Every Object In Your House Has Sensors?

Simplehuman is, despite its lofty-sounding name, not an album, nor a philosophical movement, nor even a particularly grand ecological initiative. It is, in fact, a brand, commercial, practical, and oddly specific in its ambitions. Its primary product, and the one that launched its reputation, is the kitchen bin. This wasn’t just any bin, mind you, it was marketed as one of the most high-end trash cans on the market today. This claim invites skepticism, given that bins, especially domestic ones, are rarely the subject of passionate consumer advocacy. Yet simplehuman has secured its place in the upper echelons of refuse design through a deceptively straightforward innovation: the automated lid. There are no diamonds involved, though carbon-based durability gets a nod, and no cravats or musical flourishes, just efficient engineering dressed as elegance.

The automatic sensor-activated lid is the brand's signature feature. Approach the bin, wave a hand, not too dramatically, not with fanfare, just a casual gesture, and the lid lifts itself. It's the kind of convenience that seems trivial until you've returned home late, slightly worse for wear, shoes off, kebab discreetly consumed, tiptoeing toward the bin in the dark, only to be met with a sudden mechanical whir as the lid opens unbidden. At that moment, it's either a marvel of modern engineering or a betrayal worthy of exile to the couch, depending, naturally, on whether your spouse heard it too.

The irony is that this very technology, seemingly cutting-edge, has roots stretching back to 1975 when the first general-purpose home automation protocol, X10, emerged. That system used the home's existing electrical wiring to send rudimentary signals between devices, a far cry from today's wireless sensors but equally ambitious in its attempt to liberate humanity from the tyranny of manual switches. By 2012, over 1.5 million home automation systems had been installed across American households, each promising a future where your appliances anticipated your every need, though rarely your hangovers.

Place this addition after the paragraph discussing "cradle to grave" manufacturing and before the paragraph beginning "Russell Jacoby, writing in the 1970s..."

The phrase "planned obsolescence" itself has a surprisingly long pedigree, dating to at least 1932 when Bernard London published his pamphlet "Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence," proposing government-mandated obsolescence to stimulate purchasing. But it was industrial designer Brooks Stevens who popularized the term in 1954, defining it simply as "instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary." Vance Packard, in his 1960 exposé "The Waste Makers," identified two distinct varieties: "obsolescence of desirability" (rendering functional items unfashionable) and "obsolescence of function" (engineering products to fail prematurely). The European Union has recognized the environmental impact of such practices, with the European Economic and Social Committee calling in 2013 for "a total ban on planned obsolescence" and advocating for labeling systems that indicate device durability, allowing purchasers to choose between cheap disposability and costly longevity.

The irony is that this very technology, seemingly cutting-edge, has roots stretching back to 1975 when the first general-purpose home automation protocol, X10, emerged. That system used the home's existing electrical wiring to send rudimentary signals between devices, a far cry from today's wireless sensors but equally ambitious in its attempt to liberate humanity from the tyranny of manual switches. By 2012, over 1.5 million home automation systems had been installed across American households, each promising a future where your appliances anticipated your every need, though rarely your hangovers.

These bins are advertised as unbreakable, or at least unusually resilient. Claims of durability are made with quiet confidence, though the more imaginative mind might wonder about eventual mechanical mutiny: a bin turning against its owner, flinging banana peals with robotic spite, perhaps as part of a broader uprising led by disgruntled kitchen appliances. One can picture it: the toaster joining forces with the microwave, the kettle whistling the call to arms, all under the banner of the simplehuman bin, now rebranded *complexrebel*. Alas, product lifespans rarely match their marketing promises. The inconvenient truth of modern electronics is that many devices are designed with what industry insiders call "contrived durability", a polite term for engineering products to fail just beyond warranty periods. Your sensor bin might outlive three marriages and a pair of sensible shoes, but its internal battery or infrared sensor will likely degrade precisely when replacement parts become mysteriously unavailable. This isn't conspiracy theory but economics: as designer Brooks Stevens famously defined planned obsolescence in 1954, it's about "instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary." The bin doesn't break dramatically; it merely begins to misread your gestures, opening when you're merely reaching for the kettle, or worse, refusing to open at all while you stand there holding yesterday's coffee grounds like a technological penitent.

But simplehuman's ambitions extend beyond mere refuse containment. The company has taken the sensor concept and applied it, with varying degrees of plausibility, to other household items, particularly in the kitchen and bathroom. The brand's philosophy logically extends to other kitchen tools, like its digital cooking spoon—a utensil with an integrated temperature probe to indicate when a steak has reached optimal doneness. The logic is sound in its own way: why wield a separate probe when your stirring spoon can double as a culinary diagnostic tool? Though it does raise questions about cross-contamination, and whether one truly wants to eat with the same implement that just diagnosed their meat as medium-rare. The logic is sound in its own way: why wield a separate probe when your eating utensil can double as a culinary diagnostic tool? Though it does raise questions about cross-contamination, and whether one truly wants to eat with the same fork that just told you your meat was medium-rare. Researchers studying home automation have found that consumers often develop wildly inaccurate "mental models" of how their smart devices actually work. One participant in a user study believed her iPad communicated directly with her smart lights, unaware that signals actually traveled through a cloud-based bridge system. Similarly, the sensor-fork user might imagine a direct neural connection between utensil and meat, not realizing their dinner decisions are being mediated by an algorithm that learned about steak temperatures from data collected in a Silicon Valley test kitchen.

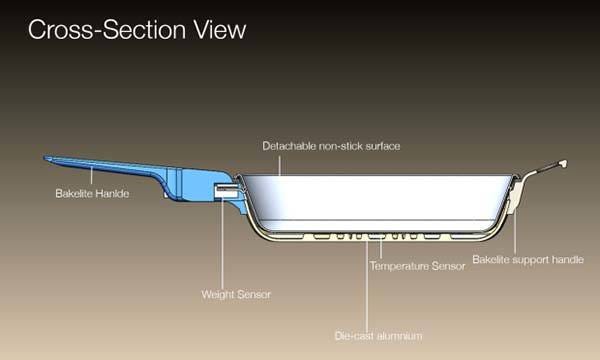

While simplehuman hasn't ventured into sensor pans, the market is flooded with "smart" cookware that makes similar promises—temperature-regulated frying pans frequently showcased on late-night shopping channels, where earnest presenters demonstrate searing techniques. The irony is that home automation once promised to save energy through intelligent systems, yet these single-purpose gadgets often represent the opposite: a consumption-driven expansion of the "smart" ecosystem, each with its own environmental footprint and likely replacement cycle. These are the kinds of products frequently showcased on late-night shopping channels, where earnest presenters demonstrate searing techniques while extolling the virtues of temperature-regulated cookware. Watching such programs is apparently a not-uncommon pastime for married individuals with limited evening entertainment options, though spouses may need to be consulted before purchasing, especially when the segment shifts to "bras" or "trousers that make your arse look better." The irony is that home automation promised to save energy and resources through intelligent systems that optimize appliance usage, running dishwashers during off-peak hours or adjusting thermostats when rooms are empty. Yet these same technologies often end up consuming additional resources through their constant standby power draw and the manufacturing footprint of replacement units when inevitably discarded. The sensor pan might help cook the perfect steak, but its environmental calculus becomes less appetizing when you consider it will likely be replaced within three years as newer models with "improved connectivity" emerge, each generation slightly incompatible with the last.

Bathroom accessories haven't escaped the sensor revolution either. Scales, for example, could conceivably be fitted with voice modules to deliver blunt feedback, "Step off, lardo. I can't take this anymore", though this remains, mercifully, hypothetical. More plausible are sensor-equipped soap dispensers, towel dispensers, and taps, all already familiar fixtures in public restrooms. The logical next step, one might think, would be toilet roll dispensers that sense dwindling supply and issue polite warnings: *"Go careful now!"* or *"If it was a curry, choose another stall."* Such devices would render toilet attendants obsolete, or at least shift their role to crowd control and emergency bog roll redistribution. The notion isn't as far-fetched as it seems. Modern home automation systems monitor occupancy through smart meters and CO2 sensors to trigger energy-saving measures. A toilet paper inventory system would merely be another data point in the home's neural network, though one suspects privacy concerns would escalate rapidly if your smart toilet began sharing usage patterns with your health insurer. After all, as one set of researchers discovered, over 87% of active smart devices remain vulnerable to security flaws because manufacturers rarely patch older models, a comforting thought when your bidet might be broadcasting your bathroom habits to the dark web.

The idea of sensor-activated toilet paper isn't entirely absurd in a commercial setting, where consistency and hygiene are priorities. But in a private home, or, say, a royal residence, the implications grow comical. Imagine the Queen, hand outstretched in a stately gesture, summoning an endless train of toilet paper that coils around her like the train of her wedding dress, until she's enveloped in a soft, fibrous chrysalis, calling out in increasingly muffled tones, *"Nooo!"* She'd resemble nothing so much as a mischievous Andrex puppy caught in its own enthusiasm.

But the other thing is, a toilet roll dispenser telling you, like you say, in a public one, that there's not much left: "Go careful now!" Isn't that what toilet attendants used to probably do? "Not that one! She's out. Use Number 1." It's only a slight exaggeration to imagine attendants stationed like air traffic controllers, clipboard in hand, monitoring usage levels and directing foot traffic accordingly. The dispenser itself might emit a polite chime, or a low amber glow, a gentle nudge toward conservation before total depletion. No coach parties allowed; no lingering. Efficiency, hygiene, and the quiet dignity of knowing exactly how many sheets remain, that's the unspoken promise. And while it may never replace human judgment, especially where curry is involved, it does eliminate the universal panic of the mid-reach discovery: smooth cardboard, no paper, only fate staring back. Security researchers have noted that the real vulnerability in home automation isn't just technical, it's psychological. We willingly invite these devices into our most private spaces, trusting them with intimate details of our daily routines, while rarely considering where that data ultimately resides. Does the smart toilet paper dispenser remember which family member consistently uses the most squares? Does it share this information with the smart scale? The ecosystem of interconnected devices creates a mosaic of personal habits far more revealing than any single gadget could capture.

And what if such dispensers came with *randomized* output? A game of Russian Toilette, where each pull might yield spearmint, capsaicin, poison ivy, TCP, witch hazel, or tea tree oil, not all of them ideal for delicate applications. One sheet in six could be a surprise: aloe vera for the lucky, porcupine quills for the unfortunate. The wheel of fortune spins, Pat Sajak intones, *"I'm sorry, that's chili."* Cue groans, frantic dabbing, and a newfound appreciation for plain, unscented, non-interactive paper. This isn't entirely hypothetical, planned obsolescence often manifests as "obsolescence of desirability," where perfectly functional products are rendered unfashionable through relentless marketing of incremental upgrades. Today's sensor bin is next year's paperweight, not because it fails, but because its design no longer aligns with the current aesthetic. The fashion cycle that once governed clothing now dictates our relationship with kitchen appliances, each generation slightly thinner, marginally more connected, and deliberately incompatible with previous accessories.

Simplehuman products are sold, predictably, in major American retail outlets, Walmart being a possibility, but more reliably at Bed Bath & Beyond. The name itself invites speculation: what, exactly, lies *beyond* bed and bath? The answer, historically, was simply *more stuff*. The chain began in 1971 as *Bed & Bath*, a name so functional it bordered on the poetic in its restraint. Founded by Warren Eisenberg and Leonard Feinstein, former executives at discount store Arlan's, the company initially focused on linens and bath products in a single New Jersey location. Growth demanded expansion, of inventory, certainly, but also of nomenclature. After some deliberation, likely brief, perhaps conducted over lukewarm coffee in a fluorescent-lit conference room, the solution was found: *Bed Bath & Beyond*. No need to enumerate the "beyond"; let curiosity (and marketing) do the work. Customers could come for pillows, stay for bath plugs, and leave with Tarot cards, if the mood struck. By the early 2000s, the chain had grown into a retail giant, acquiring specialty stores like Harmon Face Values and The Christmas Tree Shop, a venture whose name possessed an almost stubborn literalness, like a restaurant called *The Place That Sells Food*.

Bed Bath & Beyond, in turn, has absorbed other retailers over the years, including, in 2003, a company called *The Christmas Tree Shop*. The name is almost defiant in its literalness, like a store called *The Car Place* or *The Place Where You Buy Bread*. There's a certain charm in such unadorned honesty, though it does leave little room for mystery. One imagines a customer asking, *"What do you sell?"* and receiving the reply, *"Christmas trees."* End of transaction. By 2023, however, the empire began to crumble. After decades of stock buybacks that prioritized shareholder returns over operational stability, and after activist investors highlighted questionable acquisitions including the purchase of Buy Buy Baby (founded by Feinstein's sons), the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Its intellectual property was acquired by Overstock.com, which rebranded itself under the Bed Bath & Beyond name, a corporate metamorphosis that somehow feels both tragic and darkly appropriate. What lies beyond bed and bath? Apparently, digital purgatory.

Back to simplehuman: its product line concludes, fittingly, with the sensor mirror. This isn't a mirror that judges your appearance, though a Northerner-coded version might rasp, *"F***in' dreadful"*, nor one that dispenses life advice. Its function is, again, modest but potentially irksome: it turns on its own lights when you approach. Which presents an immediate paradox. If the room is dark, and you're heading toward the mirror to see yourself, how do you know you're close enough to trigger the sensor? You lunge blindly, miss the activation zone, fumble for the wall switch, bathe the room in sudden glare, then fumble again to turn it off, all while the mirror sits there, smugly illuminated, having done precisely what it was designed to do. It's the domestic equivalent of a self-driving car that brakes every time a leaf blows across the road. Microsoft researchers have documented precisely this frustration, how smart home systems often fail at the basic usability metrics that would make them truly helpful. The technology exists to create seamless experiences, but implementation lags behind promise, leaving consumers to navigate a fragmented ecosystem where each device speaks a different protocol, updates at different intervals, and inevitably falls victim to the very obsolescence it was designed to combat.

Similar frustrations attend other sensor-equipped appliances. The oven that hisses to life the moment you lean in to check the roast. The bath tap that scalds you before you've even registered its presence. The television that blares to life when you walk past the living room doorway. The gas hob that ignites with a *whoomph* the second you reach for the bacon. Each convenience carries with it the germ of its own inconvenience, like an overeager butler who lights the fireplace before you've taken off your coat, then refuses to stop stoking it no matter how much you sweat. Studies show consumers prioritize ease-of-use over technical innovation, gravitating toward "plug and play" solutions rather than complex setups requiring extensive configuration. Yet the industry continues to push features that solve problems few consumers actually have, while failing to address the basic frustrations of daily interaction. The sensor mirror doesn't need to predict your skincare needs, it simply needs to turn on reliably when you're standing in front of it, in the dark, wondering why your expensive gadgets never quite work as advertised.

The house becomes a minefield of latent automation, where every gesture risks triggering an unintended response. You learn to move with caution, to approach objects obliquely, to keep your hands clasped behind your back like a Victorian schoolchild. You whisper to your spouse across the room rather than risk activating the smart lights by raising a hand. You eat cold toast because the toaster interprets your yawn as a command. Life, in the simplehuman household, is not simpler, just differently complicated. The home automation market, now valued at over $64 billion globally, continues to grow despite these frustrations, driven by our persistent belief that technology will eventually solve the problems it creates. We keep buying sensor bins and smart mirrors because somewhere beneath the glitches and compatibility issues lies a genuine promise: that our homes might one day understand us as well as we understand them. Until then, we'll continue to tiptoe around our own kitchens in the dark, hoping the bin stays closed just one more minute.

Comments

Post a Comment