Why Did French Officers Mistake Welsh Women for British Infantry?

The Battle of Fishguard is not, as the name might suggest, a clash involving aquatic warriors brandishing flatfish as shields while brandishing swordfish in the other hand, though the image of a pike-wielding combatant squelching forward does have a certain charm. No, Fishguard isn’t a weapon at all. It’s actually a place, a small coastal town in Pembrokeshire, Wales, nestled on the northern shore of a modest natural harbour that, on a good day, can accommodate a modest merchantman or two, though not, evidently, an invading fleet. It is here, in this unassuming corner of the British Isles, that a peculiar episode of military history unfolded in 1797, a campaign so brief, so ineptly executed, and so rich in unintended farce that it reads less like a chapter of Clausewitz and more like a rejected subplot from The Admirable Crichton, had J. M. Barrie possessed a deeper knowledge of French penal policy.

Unlike many battles named for locations nowhere near the actual fighting, take the Battle of Hastings, whose precise site remains a matter of scholarly debate (Senlac Hill? Telham Hill? A field just past the petrol station?), or the ever-mysterious Battle of Waterloo, whose remnants are supposedly viewable today at Waterloo Station in central London, nestled between platforms and Pret A Manger, the Battle of Fishguard did, in fact, happen in Fishguard. More precisely, it spilled out onto the nearby headlands: Carregwastad Point, three miles northwest of the town proper, where the land juts into the Irish Sea in a series of low, windswept outcrops, and the hamlet of Llanwnda, whose church, still standing, would later bear the rather ignominious distinction of having served, however briefly, as a convict bivouac. For once, geography and nomenclature aligned neatly, sparing future tourists at least one layer of confusion. One could even argue that the battle’s name is unusually generous to Fishguard: the actual fighting was so minimal that “The Unfolding of Events Adjacent to Fishguard” might have been truer, if less punchy.

This was no Viking raid, nor a Victorian-era squabble over tin mines or railway timetables, nor even a flare-up in the Cod Wars of the twentieth century, when Icelandic trawlers squared off against Royal Navy frigates in a maritime tiff best described as passive-aggressive. Rather, it took place during the War of the First Coalition (1792–1797), a broad European alliance formed, rather optimistically, to contain revolutionary France in its more exuberant phase. At this point, Britain was engaged in hostilities with, essentially, everyone, though France, as ever, was the headline act, the nation whose very existence as a republic seemed, to Pitt’s cabinet, a provocation in itself. The invasion of Wales was never meant to be the main focus of French strategy. Instead, it served as a diversionary operation, one prong of a three-legged stool of ill-conceived invasions, all dreamed up by the ambitious General Lazare Hoche: one force to land in Ireland (the main effort), one near Newcastle-upon-Tyne (to alarm the coalfields), and one in Wales, ostensibly to march inland and seize Bristol, though no one appears to have consulted a map on the gradient of the Brecon Beacons, or the likelihood of Welsh farmers permitting a column of convicts to tramp across their leeks unchallenged. Geographically, this made a certain amount of sense: if one were sailing from the northwestern coast of France, say, the general area near Brest, where the Atlantic gales whip in with particular enthusiasm, one would naturally pass the southwestern coast of Wales before arriving at Ireland. It was, as some might put it, a stop on the way. An unplanned stop, as it turned out.

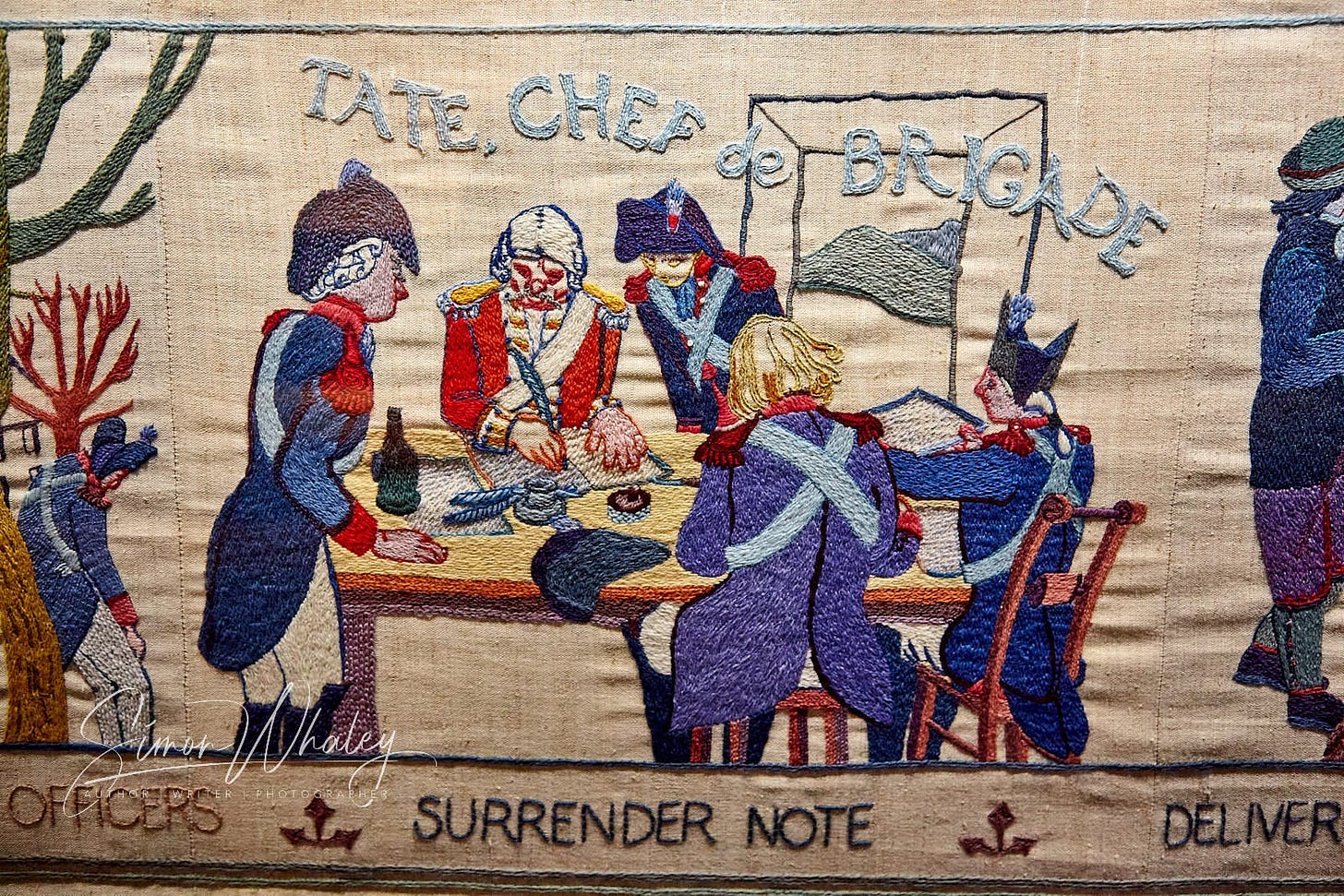

The force assigned to this Welsh diversion was the Légion Noire, the Black Legion, numbering around 1,400 men and commanded by Colonel William Tate, an Irish-American officer whose surname inevitably invites art-world associations, though no Tate Modern had yet been conceived in 1797, and certainly no modern art accompanied the expedition (unless one counts the interpretive dance of drunken looting that followed disembarkation). Tate himself was a man of improbable trajectory: born in County Louth, raised in South Carolina, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, fighting against the British, naturally, and later commissioned by the French consul to raise an army to invade Spanish Florida, a plan so audacious and underfunded it collapsed before launch, earning him accusations of treason back home. Exhausted and penniless, he fled to Paris, where, in the peculiar logic of the Directory, his very failure marked him out as suitable for the Welsh expedition. He was 44, not the doddering septuagenarian some later accounts insisted upon, a misattribution that likely arose from a careless footnote in a 1950 monograph and persisted, like so much history, through sheer inertia.

The composition of the Black Legion was… eclectic. Roughly 600 of the troops were French regular soldiers, though not exactly the cream of the military crop, having been deemed surplus to requirements for Napoleon’s concurrent, and rather more successful, campaign in Italy. These were the reliable core, men who still saluted, still loaded their muskets, still answered to “En avant!” without giggling. The remaining 800 were classified as “irregulars,” a term that, in this context, served as a bureaucratic euphemism for something rather less flattering: republicans whose zeal had outstripped their discipline, deserters from both French and allied armies, convicts plucked from the hulks or the bagnes of Toulon, and, perhaps most ironically, royalist prisoners, men who had been clapped in irons for refusing to swear allegiance to the Republic they were now expected to defend. In theory, they were to be paid in plunder; in practice, they were paid in promises, most of which dissolved the moment they touched Welsh soil.

The naval escort, under Commodore Jean-Joseph Castagnier, was rather more impressive: the frigates Vengeance and Résistance (the latter on her maiden voyage, a touch of optimism not shared by her passengers), the corvette Constance, and a lugger, the Vautour, a nimble little vessel whose name, meaning “vulture,” proved prophetic, if not in the way intended. These ships had slipped out of Brest on 16 February, flying Russian colours in a half-hearted attempt at subterfuge, the naval equivalent of wearing sunglasses and a false moustache. Their mission was to deposit Tate’s men and then hasten west to rendezvous with Hoche’s main fleet, returning from its own abortive attempt on Bantry Bay, an encounter that, like so much else in this campaign, never materialised. The weather, that eternal arbiter of amphibious operations, had already scuppered the Irish landing; it would soon undo the Welsh one as well, this time through something far more insidious than gales: a cellar.

Unsurprisingly, discipline among this contingent proved somewhat fragile. Upon landing near Fishguard on 22 February 1797, under cover of darkness and with seventeen boatloads of men and matériel, 47 barrels of gunpowder, 50 tons of cartridges and grenades, 2,000 stands of arms, the irregulars promptly began to melt away, Instead of an orderly tactical retreat, they scattered enthusiastically toward nearby farmhouses and villages. Their goal was loot, rather than any kind of strategic positioning. Specifically, they were after wine. And not just any wine: Portuguese wine, in significant quantity. A shipwreck had recently deposited a cache of casks, likely port, along the Welsh coast, the kind of windfall that would have gladdened the heart of any sailor, but which, in the hands of poorly supervised convicts, became an engine of chaos. The resulting bacchanalian chaos did little to improve unit cohesion. One might imagine French officers attempting to restore order with increasingly desperate cries of “No naughty running away while you’re at it, I want you all here by teatime, you understand? You’re on your honour!” But honour, it seemed, was in short supply, and the wine was very good. One group, seeking shelter from the February chill, broke into Llanwnda Church and lit a fire using the pews as kindling and a Bible as tinder, an act less of sacrilege than of sheer, alcohol-fogged practicality. If only they’d known: the press gangs of Milford Haven were already mustering.

Meanwhile, on the British side, matters proceeded with considerably less urgency, and rather more tea. The local commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Knox, 28 years old, possessor of a purchased commission, and entirely lacking in combat experience, was presiding over what appears to have been a social gathering at Tregwynt Mansion, possibly involving brandy and certainly involving small talk about livestock, when a messenger on horseback arrived with news of the French landing. Knox’s initial reaction was reportedly one of mild surprise: “Really?” It took some time for the implications to sink in. There was no immediate scramble to arms, no urgent dispatch of riders with flaming arrows. One gets the sense that everyone involved was operating on what might generously be called “Welsh time,” a tempo measured in the leisurely span between milking and supper rather than in minutes.

When the British response finally took shape, command fell to Lord Cawdor, John Campbell, 1st Baron Cawdor, captain of the Castlemartin Troop of the Pembroke Yeomanry Cavalry, rather than to Knox. At the time, Cawdor was thirty miles away at Stackpole Court, occupied with the grim task of preparing for a funeral the next day. Upon receiving the news, he did not send a subordinate. He assembled everyone, his yeomanry, the Pembrokeshire Volunteers, the Cardiganshire Militia, even the press gangs and crews of two revenue cutters from Milford Haven, totalling some 150 sailors, and set off for Haverfordwest, where he picked up another 250 militia under Lieutenant-Colonel Colby and commandeered nine cannon, six of which were hauled into the town’s castle and three loaded onto carts for the march to Fishguard. It was a ramshackle coalition, yes, but a determined one, and crucially, one that arrived before the French had finished uncorking their third cask. He led them all from the Royal Oak, a local pub that served as his headquarters, instead of the more traditional tent or manor house. Pubs in this era were more than just places to drink; they functioned as impromptu civic centres, venues for inquests, court hearings, and local administration. So when Cawdor commandeered the Royal Oak, he was, in effect, occupying the town’s de facto town hall, its war room, and its dispatch office, all under one thatched roof. His forces, drawn from local yeomanry and militia, marched out with the slightly unsteady determination of men who had perhaps overindulged the night before. Even so, they managed to haul three cannon up Trefwrgi Lane as daylight faded.

As evening fell, the French withdrew to their temporary encampments, Trehowell Farm, on the Llanwnda Peninsula, became Tate’s headquarters, while the disciplined grenadiers under Lieutenant St. Léger dug in on the high rocky outcrops of Garnwnda and Carngelli, gaining an unobstructed view of the surrounding countryside. Unbeknownst to Cawdor, they even prepared an ambush along the hedgerows of the lane he would later retreat down, an ambush that never sprung, thanks only to the failing light and a well-timed change of heart. The French command was fraying: Castagnier, seeing no sign of Hoche and sensing the tide turning, had already weighed anchor and sailed off with the Vengeance, abandoning his infantry to their fate. Tate, deprived of escape and surrounded by mutinous, wine-sodden subordinates, was receiving increasingly urgent counsel from his Irish and French officers: surrender, and surrender soon. At least six men, Welsh and French alike, had already died in confused, close-quarters brawls that broke out when a looter crossed paths with a farmer armed with a pitchfork and firm views about his hens, rather than in any formal battle.

And here, legend, though plausibly grounded in fact, steps in. As the French officers looked out from their positions on the morning of the 24th, they reportedly saw figures gathered on the cliffs above Fishguard: tall, dark silhouettes with distinct, angular headgear and bright red garments. To a weary, perhaps still tipsy foreign officer squinting into the morning light, his vision clouded by fatigue and the lingering fumes of Portuguese port, these might well have appeared to be a fresh battalion of British infantry: shakos and red coats, those unmistakable emblems of regular troops. In reality, they were local women, dressed in the traditional Welsh costume of the time: high, stiff black hats, not unlike military shakos from a distance, especially when viewed from below, and long red whittles, or woollen shawls, wrapped tightly against the coastal wind. There were no field glasses to clarify the error, no staff officer on hand to murmur, “Er, sir, that’s Mrs. Jenkins from the post office, and her sister, and the vicar’s wife, and they’re carrying bread, not bayonets…” The optical illusion, aided by exhaustion and anxiety, was apparently convincing enough. And somewhere in this tableau moves the figure of Jemima Nicholas, a cobbler by trade, and, according to oral tradition, a woman of formidable presence, who is said to have single-handedly captured twelve French soldiers (armed men, presumably not at their peak sobriety) and marched them, like errant schoolboys, into St. Mary’s Church for safekeeping. She may even have rallied other women, dressing them in their best hats and cloaks to augment the illusion. Alas, no contemporary account mentions her, no dispatch, no diary, no parish register. Her story exists in that fertile borderland between history and folklore, where deeds are too good not to be true, and too undocumented to be proven. Like the Loch Ness Monster, but armed with a pitchfork and better posture.

The speculation about the Welshwomen on the cliffs is just that, speculation, but it persists, lodged in the folklore like a stubborn bit of shell in an oyster. It’s the kind of story that feels true even if the documentation is thin, the kind that gets passed down in Beano annuals and shipping forecasts alike, two equally valid if unconventional paths to historical literacy. Someone, at some point, must have looked up and sworn, beyond doubt, that those silhouettes meant business. And who could blame them? A tall black hat, sharply peaked, casting a rigid outline against the grey February sky; a deep red woollen garment, flapping in the coastal wind, seen from a distance, through the haze of fatigue and residual port fumes, the resemblance to a line of infantry was, if not exact, at least plausible enough to tip the scales. It’s not that the French were particularly gullible; it’s that expectation shapes perception. When you’re already outnumbered, already doubting your own side’s cohesion, already smelling defeat in the air like salt and stale wine, then yes, a line of women watching from the headland might look, for a few critical minutes, like the vanguard of a fresh brigade arriving just in time.

And let’s not discount Lord Cawdor’s performance. His refusal of the conditional surrender wasn’t mere stubbornness; it was theatre of the highest order. He knew, must have known, that once you begin negotiating terms, the psychological advantage shifts. Accept a conditional surrender and you acknowledge parity, or at least the possibility of prolonged resistance. Demand unconditional surrender, and you project invincibility, even if your own men are queasy from last night’s festivities, your ammunition is running low, and your best artillery team consists of three sailors who learned gunnery by watching someone else do it once. What matters is the posture. “You can’t come into the pub because it’s full of men, full of them, you hear, full of them,” he might as well have said through the door. “Well, no you can’t, you simply can’t come through the door. I can’t accept your surrender, there’s far too many of us. Bye. Well, lads.” It’s bluffing, pure and simple, but bluffing backed by timing, by location, and by the accidental reinforcement of local fashion.

The aftermath was as understated as the battle itself. Tate, briefly imprisoned at Haverfordwest Castle, did not linger in British custody. Most of the Black Legion were repatriated in a fashion that resembled an awkward delegation being politely escorted back to the ferry, rather than prisoners of war in the later, Geneva-Convention sense. Their humiliation was softened only by the fact that no one in Paris was especially eager to see them again. Discipline had broken down, yes, but not entirely along the lines one might expect. The royalist prisoners, in particular, had little incentive to fight for the Republic that had jailed them in the first place, and their desertion was less betrayal than logical self-preservation. Meanwhile, the looting, mostly of wine, some food, possibly a few chickens, was opportunistic rather than systematic. These were not seasoned raiders stripping the countryside bare; they were men who had been told to invade, handed rifles, and then left largely to their own devices the moment land was sighted. Given the choice between standing in formation or uncorking a cask of washed-up port, many opted for the latter. And who wouldn’t? As one observer might have muttered, after the fact, watching the French stumble back toward their boats: “Oh, hang on. Because Wales, boat wise, is on the way to Ireland, isn’t it? Sure!” It was, fundamentally, a matter of geography, and perhaps poor planning. The soft underbelly of England, as someone quipped, turned out to be less soft and more… inconveniently located. The messenger on horseback, the brandy, the slow dawning of the import of the news on Knox, all of it contributed to a rhythm of delay that the French, already fracturing, could not afford to match.

And so, with two officers knocking, using gloved fists rather than hooves, though that image has its charms, the last invasion of mainland Britain ended in a negotiated signature and the quiet clink of empty bottles rolling in the surf, rather than in a bang. Tate signed the articles of surrender at Trehowell Farm, the original document, fittingly, has been lost to time, perhaps used to light a fire in some subsequent century. By 4 p.m., the French prisoners were being marched through Fishguard toward Haverfordwest, their muskets piled on Goodwick Sands in a neat, if ignominious, heap.

But the ripples spread further than Wales. When news reached London a few days later, it sparked a financial panic rather than a military one, a run on the Bank of England, as note-holders hurried to exchange paper for gold, a right still printed, quite sincerely, on every banknote: “I promise to pay the bearer on demand…” Unfortunately, the Bank held only £5.3 million in gold against £10.8 million in notes, a discrepancy that had been manageable until someone landed in Pembrokeshire. On 27 February, Parliament passed the Bank Restriction Act, suspending specie payments for the first time in history. Overnight, British banknotes became inconvertible, a precedent that would last until 1821, and whose philosophical shadow still stretches across every pound in your wallet today. So, in a sense, the Battle of Fishguard didn’t just repel an army; it redefined money itself. A fitting legacy for a conflict in which the decisive weapon may have been a red shawl.

The naval epilogue came weeks later: on 9 March, HMS St Fiorenzo and HMS Nymphe, commanded by Sir Harry Neale and Captain John Cooke, encountered the crippled Résistance and Constance, abandoned mid-voyage, their masts shattered by the same Irish Sea gales that had foiled Hoche. After a brief, bloodless engagement (18 French killed, 15 wounded; zero British), both ships surrendered. They were re-commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Fisgard and HMS Constance, a quiet irony: the very vessels that brought invasion now bore names that echoed British defiance.

Faced with what they believed to be a growing and well-equipped British force, and with their own ranks diminished by desertion, inebriation, and the departure of their navy, the French command concluded resistance was futile. On 24 February, just two days after landing, Colonel Tate signed the articles of unconditional surrender. The terms were surprisingly lenient: Tate and his officers were briefly imprisoned, but most of the French troops were soon repatriated in a prisoner exchange in 1798. The whole affair had lasted less time than a modern bank holiday weekend, less, even, than the average family argument about whose turn it is to do the washing-up.

The Battle of Fishguard is remembered today for a single remarkable reason: it marked the last successful landing of a hostile foreign force on the mainland of Great Britain. Its scale and strategic impact were minimal, yet its historical significance endures. This fact is proudly inscribed on memorial plaques in the area, a quiet corrective to the widespread assumption that 1066 marked the final such incursion. Hastings may loom larger in the national imagination, with its tapestries and tragic arrows, but Fishguard holds the more recent, and far stranger, honour. There were no grand charges, no decisive cavalry maneuvers, no legendary last stands. There was wine, confusion, mistaken identity, bureaucratic euphemism, and a pub that doubled as a command centre. And somewhere on the cliffs above, a group of Welshwomen in traditional dress stood, entirely unaware that their millinery and fabric had just helped repel an invasion. They were armed only with dignity, shawls, and the unshakeable conviction that such behavior had no place in Pembrokeshire.

Comments

Post a Comment