Why Mars Has a Flag But No Country to Fly It

Red, Green, Blue Mars

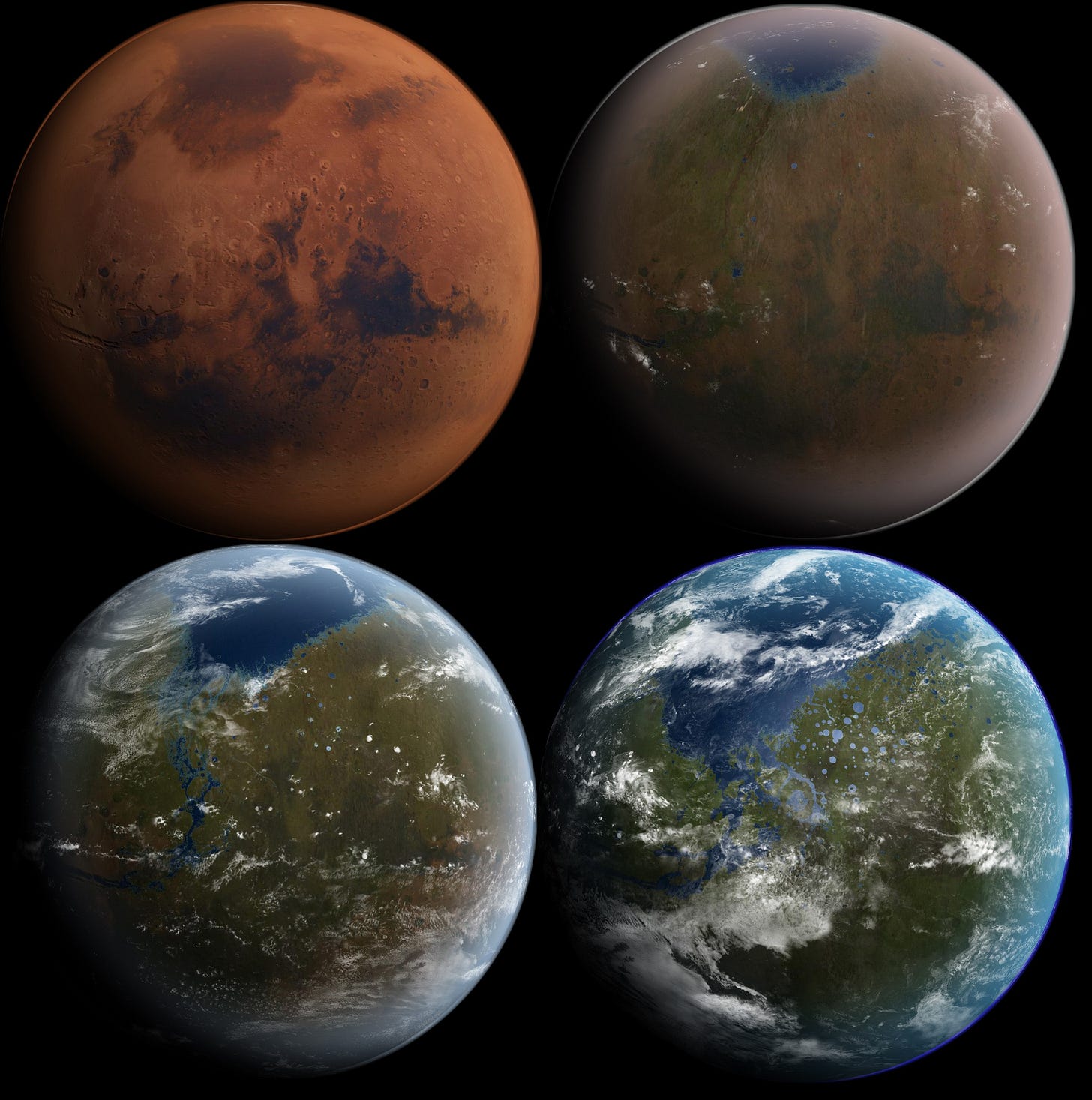

The flag of Mars presents a curious case, an emblem without a nation, a symbol adrift in legal and celestial uncertainty. It is not red in the way one might expect, not a simple homage to the planet’s rusty hue, nor does it feature a Mars-shaped disc like some interplanetary ensign. Instead, it is a tricolor: red, green, and blue, arranged horizontally. The design draws directly from Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy, Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars. Each band represents an epoch as much as a color: red for the barren, unaltered world, its iron oxide plains stretching beneath a thin, cold sky; green for the age of tentative terraforming, when engineered lichens, mosses, and hardy grasses begin to creep across the regolith, softening the desolation into something vaguely pastoral, a country park on a planetary scale, perhaps with picnic areas near the Tharsis bulge; blue for the distant future, when a thickening atmosphere allows liquid water to pool in the Valles Marineris, forming shallow seas beneath newly formed cloud systems, completing the transition from dead rock to living world.

Which brings us, inevitably, to football on Mars.

With surface gravity at roughly 0.37g, about a third of Earth’s, the sport would undergo radical transformation. Headers, for instance, would be sublime: a player could launch vertically with ease, meet the ball at its apex, and guide it with languid precision. Jumping over an opponent would not be showboating, it would be baseline mechanics. Tackling would require recalibration; a mistimed lunge could send both players tumbling in slow motion, limbs akimbo, like astronauts in a docking rehearsal. The ball itself would behave unnervingly: a firm strike might not return for ten seconds or more, arcing high into the thin atmosphere, drifting past the goalposts, perhaps vanishing over the horizon if struck with enough force. Control would be near impossible unless the game were played indoors, under a pressurized dome, naturally, with a ceiling. Then the rules would need rewriting: off the walls? Off the roof? Brazilian futsal, but vertical. A skilled dribbler could run up the curved wall of a half-pipe pitch, plant a foot on the ceiling, and flick the ball over a defender’s head, all while spectators in breathing masks cheer from padded bleachers. The spirit of the game? That would have to be renegotiated. On Mars, the spirit of the game *is* Mars.

This raises the prospect of Mars City United, or perhaps just Mars City, if population density permits only one professional side. Their home advantage would be absolute: acclimatized musculature, bone density adapted to lower load, an instinctive feel for parabolic trajectories. Earth-based teams, even in pressurized suits, would flounder, stiff, sluggish, perpetually off-balance. Away crowds would be sparse, less from lack of enthusiasm than from the sheer logistical nightmare of attending: a three-month transit, radiation shielding, re-entry protocols, and the ever-present risk of explosive decompression during extra time. Broadcasts would feature commentators murmuring, “And it’s a very lifeless crowd here today…” over footage of five thousand spectators in oxygen hoods, barely moving. Years later, native Martians, taller, leaner, with elongated torsos and strangely graceful gaits, would regard Earthlings as squat, heavy-limbed curiosities, like visiting Neanderthals at a symposium on orbital mechanics.

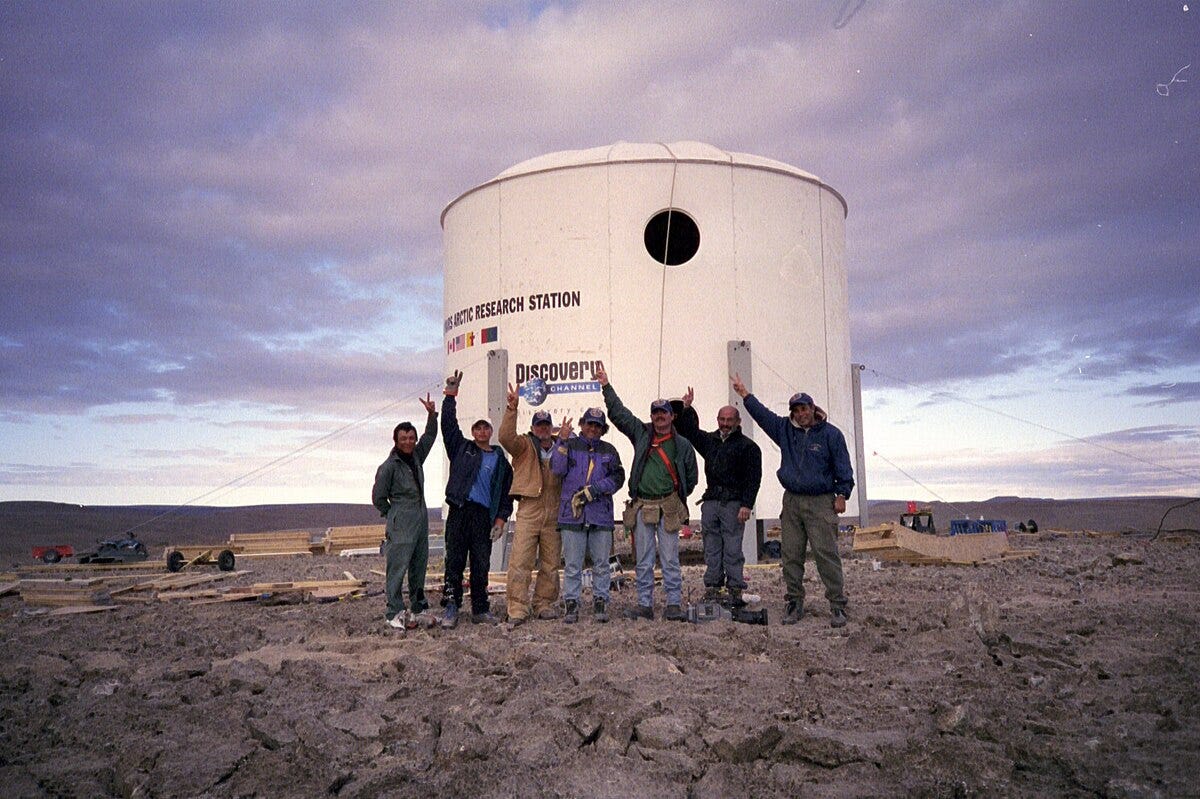

This arms race, however fanciful, runs aground on a single legal obstacle: the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. Ratified by over a hundred nations, it explicitly prohibits weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies, and, crucially, declares that the Moon, Mars, and all other extraterrestrial real estate are the “province of all mankind,” not subject to national appropriation. No planting flags, no claiming quadrants, no selling deeds to Martian bungalows (despite the persistent entrepreneurs who do exactly that). The treaty is why the Mars flag, however evocative, remains unofficial, a piece of speculative heraldry, flown only where terrestrial law permits symbolic indulgence. And such a place exists: the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station. Yes, despite the name, it lies in the Canadian High Arctic, on Devon Island, rather than in Venezuela. The site was chosen for its barren, Mars-like terrain: permafrost, impact craters, wind-scoured valleys, and almost no vegetation. There, beneath a dome of reinforced polymer, the tricolor flies as a thought experiment made fabric, fluttering in the -30°C breeze while researchers simulate dust storms and test life-support redundancy.

Other fictional Mars flags have surfaced in literature. Robert Heinlein’s *Stranger in a Strange Land* proposed a stark white field bearing only the astronomical symbol for Mars, the circle-and-arrow glyph, long associated with masculinity and war. The result, unintentionally, would be a planetary banner reading, in essence, “MEN!”, a cosmic restroom sign scaled to planetary ambition. It’s hard not to chuckle: planting such a flag at the summit of Olympus Mons would be less a claim of dominion, more a declaration of hormonal imbalance.

Meanwhile, Mars itself remains indifferent, geologically quiet, atmospherically thin, its days 40 minutes longer than Earth’s, its seasons stretched over nearly two terrestrial years. Dust devils spiral across Hellas Planitia. Frost gathers in the polar caps, first water ice, then a veneer of frozen CO₂ in winter. The sky, depending on the hour and the dust load, shifts between butterscotch, pale pink, and a cold, high-altitude blue. There is no sound, save what your suit transmits: the hiss of oxygen, the crackle of static, the crunch of regolith under boot. You could stand at the edge of Valles Marineris, ten times longer and five times deeper than the Grand Canyon, and hear nothing but your own breath. No birds. No wind in trees. No distant traffic. Only silence, and the faint, rhythmic thump of your heart, reminding you that you are very far from home.

Still, the idea persists: *we could live there*. Not today. Not for decades. But someday. A domed city at the edge of a glacier-rich crater. Solar arrays fanning across the plain. Greenhouses pressurized and warmed, lit by LEDs tuned to chlorophyll absorption peaks, where wheat and kale grow in hydroponic trays while outside, the temperature hovers at -60°C. The air inside would smell of damp soil, ozone, and coffee, strong, black, carefully rationed. People would develop rituals: watching dust storms approach like slow-motion tsunamis on the external monitors; celebrating “First Bloom” when the first tomato ripens; naming children after Martian features, Ares, Candor, Echus. They’d tell stories about Earth the way islanders tell stories about the mainland: mythologized, distant, lush beyond belief. “They say it rains *every day* somewhere. And the oceans? Covered in saltwater. You could *swim* in it.” A pause. “Bare-skinned.”

Of course, the transition wouldn’t be seamless. Muscle atrophy, radiation exposure, bone loss, these belong less to the realm of engineering than to that of biology, a series of negotiations between body and environment. A child born on Mars would likely never be able to visit Earth without a reinforced exoskeleton and months of acclimatization; their cardiovascular system simply wouldn’t cope with 1g. Earth-born adults, arriving in middle age, would find themselves suddenly powerful, able to leap over boulders, lift equipment with one hand, sprint with bounding, kangaroo-like strides, until their bodies began to rebel. The heart, no longer fighting gravity, would weaken. Blood would pool oddly. Balance systems, calibrated for Earth, would misfire. You’d reach for a tool, misjudge the inertia, and send it spinning lazily into the ceiling. Everything would have to be learned again: how to walk, how to pour water, how to turn a wrench, how to catch a falling object. Even sneezing would be hazardous.

And yet, the appeal endures. It would be less an act of conquest than one of participation. To see a sunset that lasts twice as long, painted in hues no artist can replicate. To stand where no human has stood, and leave the first footprints in a new epoch. To look up and see Earth is to see it transformed from home into a star, a pale blue dot, hanging in the black, impossibly fragile and impossibly dear.

There is somewhere on Earth where the Mars flag is flying right now, officially, by decree of a research protocol. Specifically, it flies at the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station, a name that, despite inviting assumptions, does indeed place it in the Arctic, precisely on Devon Island in Nunavut, Canada. The station serves as an analog habitat, where crews live in isolation for weeks or months, simulating Martian surface operations: simulated EVAs in bulky suits, communication delays with “Mission Control,” and reliance on closed-loop life support. Its existence underscores a quiet irony: the only official Martian flag currently aloft waves beneath the aurora borealis, battered by snow and katabatic winds that mirror, in relentlessness if not in substance, the dust storms of the planet it evokes. The flag itself, red, green, blue, is affixed to a mast beside the habitat airlock, visible in mission photos, slightly faded, occasionally crusted with frost. It serves neither as a declaration of sovereignty nor as a veiled corporate emblem, but as a visual shorthand for intent, a reminder that every airlock cycle, every soil sample, every system check is a kind of rehearsal. No one salutes it. Maintenance crews don’t pause as they brush ice from its fibers. Yet its presence is deliberate, a thread connecting speculative fiction to operational protocol. In its own way, it stands as the most Mars-like object on Earth, defined through attitude rather than appearance; like the planet itself, it waits. Patient. Uninhabited. Full of implication.

And somewhere, in a quiet drawer at NASA or ESA or JAXA, there is a folded prototype of a different one: simpler, sturdier, designed to survive deployment in a dust storm. It waits to be seen, to be answered, to signal rather than to claim. To say, in its quiet, flapping code: We are here.” And perhaps, quietly, beneath that: *We made it.*

One hell of an away trip.

But the flag’s journey didn’t begin on Devon Island. It began, in a sense, in 1999, when Pascal Lee, a planetary scientist and co-founder of the Mars Institute, first unfurled his tricolor at the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station. Lee, who had spent years studying Martian geology and polar processes, saw the flag as more than a nationalist symbol. To him, it was a narrative device, a way to visualize the planet’s transformation. The red band, he explained, represented the planet’s memory: billions of years of volcanic desolation, dust storms that could engulf the entire globe, and perchlorate-laced soil capable of poisoning any unprotected seed. The green spoke of intention, the moment when humans, armed with cyanobacteria and genetically modified ryegrass, begin to nudge the planet toward habitability. And the blue? That was *aspiration*, a future where the average temperature might rise from -63°C to something approaching survivability, where the atmospheric pressure might climb from 0.6% of Earth’s to, say, 19 kilopascals, just enough to sip oxygen through a mask instead of a helmet.

Lee’s flag was flown into space aboard STS-103 in 1999, carried by astronaut John Grunsfeld, a veteran of five shuttle missions and later NASA’s Associate Administrator for Science. It wasn’t the first flag to leave Earth, of course. Yet it was the first to carry the idea of Mars as a place, a project rather than a destination. Grunsfeld, who would later become a vocal advocate for human missions to Mars, described the experience as “planting a seed in orbit, even if the soil is still 140 million miles away.” The flag returned to Earth, was briefly displayed at the Smithsonian, and then returned to Lee, who continues to fly it at analog stations around the world: in the Utah desert, on the rim of a Hawaiian volcano, and once, memorably, at the South Pole, where the temperature dropped low enough to make even the *idea* of green seem absurd.

Meanwhile, the literary lineage of Martian flags stretches back further still. In 1984, Thomas O. Paine, former NASA Administrator and architect of the Apollo program, designed a flag that never flew in space but nonetheless captured the imagination of planetary scientists and science fiction writers alike. Paine’s design featured a sliver of Earth in the hoist, a star in the fly, and the astronomical symbol for Mars in the center: a circle with an arrow pointing toward the star. It was, he said, “a reminder of where we came from, and where we are going.” The flag was illustrated by Carter Emmart, now the Director of Astrovisualization at the American Museum of Natural History, and published on the cover of *The Planetary Report*. In 2005, it was awarded to Ray Bradbury, author of *The Martian Chronicles*, during a ceremony at the Planetary Society’s 25th anniversary. Bradbury, then 85, accepted the flag with characteristic lyricism: “We are the children of the red dust,” he said. “We carry Mars in our bones.”

Heinlein’s *Stranger in a Strange Land* offered a more minimalist take: a white field emblazoned with the Mars symbol, simple, stark, and unintentionally hilarious. The effect, as noted, is less “planetary identity” and more “restroom door in space.” Yet even this has its roots in astronomical tradition: the circle-and-arrow glyph dates back to the 18th century, when it was first used to represent the planet in almanacs and star charts. The symbol itself, ☉ with an arrow, was never meant to denote masculinity originally; that came later, when Roman legions needed a shorthand for armor grades and Roman astrologers needed a glyph for the war-god’s planet. By the time Kepler slipped it into the margin of De Stella Martis it had already picked up the baggage of iron, blood, and soldiering, a neat psychological trick that makes a flag bearing nothing but the planet’s sigil feel slightly belligerent, as if the whole world were being drafted into a regiment whose barracks happen to be 225 million kilometres away.

Kim Stanley Robinson insists he never intended the tricolor to become a vexillological hit. In a 1997 lecture at the Smithsonian he admitted he needed “a quick way to tell the reader which century we’re in” and simply painted the planet’s traffic-light sequence across the dust jacket. The audience laughed, but the next year a JPL engineer arrived at a Mars Society conference with a hand-sewn version; by 2001 the Mars Arctic Research Station had raised it over Devon Island’s Haughton Crater, a 23-million-year-old scar so lunar-bare that even the local musk-oxen give it a polite detour. The fabric, nylon rip-stop, the same stuff used for parachute canopies, was chosen because it laughs at −50 °C and doesn’t mind being sand-blasted by wind that has already crossed two thousand kilometres of permafrost without meeting a single tree.

Flag etiquette, however, remains improvisational. During the 2005 field season the crew forgot to bring a halyard; they ended up lashing the pole to the station’s ATV trailer hitch and raising colors every morning after checking the weather station that records humidity so low it would make a mummy cough. One analogue astronaut, a soil chemist from Boulder, confessed in her mission journal that saluting felt “goofy, like pledging allegiance to a geology textbook,” but she did it anyway because the ritual reminded her that the walk outside, bulky suit, fifteen-minute depress, horizon curving nowhere, was practice, not performance.

The colours have started to drift from their literary moorings. Red is still the baseline planet, but it is also the colour of the perchlorate-rich dust that clogs rover filters and stains white spacesuits the shade of old brick. Green now nods toward the cyanobacteria trials at the University of Arkansas, where extremophile mats survive 600 pascals of pressure and UV flux that would sunburn a rhino. Blue, once the dream of open sky, has been quietly re-coded by ecopoiesis researchers: the first visible shoreline will almost certainly be inside a pressurised dome, a puddle the size of a tennis court that will still feel like an ocean to people who have never heard surf.

No one has yet trademarked the design, though the Mars Society once threatened legal action against a souvenir shop selling tricolor boxer shorts “guaranteed to make your own personal space programme lift off.” The case was dropped when it turned out the vendor was a sixteen-year-old fan who had dyed the shorts in his parents’ bathtub and was donating proceeds to the same research station whose logo he had, technically, infringed.

Meanwhile, the real flag waits, probably in a Tyvek sleeve inside a climate-controlled drawer at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, tagged “Mars Conceptual, Not Flight-Ready,” next to a vial of simulated regolith and a note reminding future mission planners that colourfast dyes behave oddly under 0.38 g and continuous low-level radiation. The label is dated in pencil: 2117, the same year the United Arab Emirates has pencilled in for its proposed Martian settlement. Coincidence, perhaps, but flags have always been better at predicting the future than calendars.

Over time, it became shorthand for “male,” but its original meaning was orbital: the circle is the planet, the arrow is its eccentric path through the sky. In this context, Heinlein’s flag becomes a diagram: a kind of cosmic infographic, legible to anyone who remembers their high school astronomy.

The Expanse series, both in book and television form, offers perhaps the most politically nuanced flag: a bifurcated field of orange and black, with a hollow red circle representing Mars and a blue crescent symbolizing the ongoing terraforming effort. The orange and black stripes are not just aesthetic, they reflect the planet’s dual nature: the orange of rust and dust, the black of space and silence. The crescent stands for promise, a sliver of blue that might, in centuries, widen into a sky. The flag was designed by Jonathan Hunter, a graphic artist who worked closely with the show’s creators to ensure that every element felt *earned*. The result is a banner that looks less like a national flag and more like a *mission patch*, the kind you’d sew onto a pressure suit before a long haul to the Belt.

All of which is to say: the flag of Mars is not *one* flag. It is a *conversation*, between science and fiction, between aspiration and law, between the planet we see and the planet we *imagine*. It is a tricolor flown in the Arctic, a white sheet in a novel, a patch on a spacesuit, a doodle on a whiteboard at JPL. Above all, it serves as a placeholder, a stand-in for a future that has yet to arrive, one we continue to rehearse, mission by mission, across these earthly analogs.

And somewhere, in a quiet drawer at NASA or ESA or JAXA, there is a folded prototype of a different one: simpler, sturdier, designed to survive deployment in a dust storm. It waits to be seen, to be answered, to signal rather than to claim. To say, in its quiet, flapping code: We are here.” And perhaps, quietly, beneath that: *We made it.*

One hell of an away trip.

Comments

Post a Comment