Why Victorian Criminals Were Sold as Folk Heroes (With Burglary Kits Included)

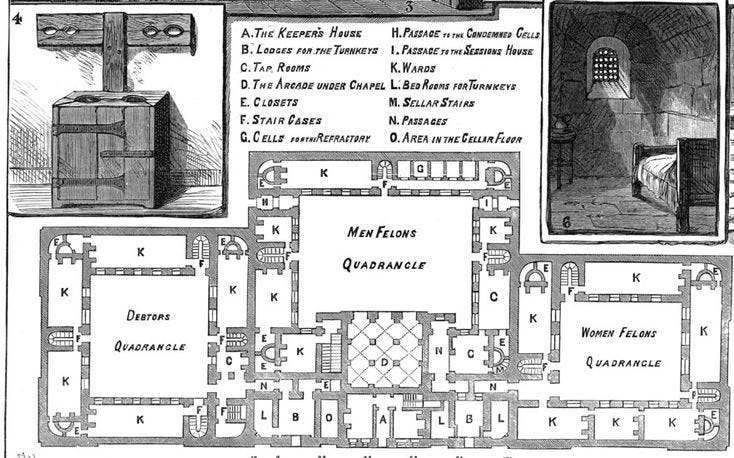

The Newgate Novel. It begins, as many cultural phenomena do, with a publication, dry, official, unassuming. The *Newgate Calendar*, named after London’s infamous Newgate Prison, started life as a monthly bulletin of executions. A grim ledger, really: names, charges, dates, and outcomes. A calendar of prisoners due to be tried or hanged later in the year. Straightforward, functional, and suitably solemn in its bureaucratic morbidity. The Keeper of Newgate, that sober functionary in his threadbare black coat and clanking keys, would compile the lists with the same dutiful precision with which a grocer tallied tins of sardines, only here, the inventory was of souls, measured not in ounces but in years, months, and final, unappealable drops of the trapdoor.

But function gave way to fascination. Publishers, ever alert to public appetite, seized upon the raw material and spun it into something else entirely. The dry entries became embellished. The condemned became characters. The calendar, once a list, transformed into a series of biographical chapbooks, cheap, small, widely distributed pamphlets recounting the lives and misdeeds of notorious criminals. These weren’t dry legal records; they were lurid, sensational, and wildly popular. The public didn’t want mere facts, they wanted drama, pathos, bravado, downfall. They wanted stories. And the chapbook vendors were happy to oblige, often cribbing directly from the Calendar but seasoning the fare with liberal helpings of invention and moralising doggerel. Sawney Bean’s cannibal clan, Dick Turpin’s midnight rides, Moll Cutpurse’s swaggering defiance, each bore only the faintest resemblance to documented reality. Truth bent beneath the weight of narrative necessity, and the public, gathered in common lodging-houses with a single tallow dip between five orphans, devoured every word as Henry Mayhew recorded: not silently, but aloud, in communal rites of shuddering delight.

This wasn’t high literature, at least not in the traditional sense. Chapbooks occupied a peculiar cultural niche: accessible, disposable, and unapologetically entertaining. They were the pulp fiction of their day, passed hand to hand, read aloud in taverns, tucked into waistcoats for later perusal. Their audience spanned classes, though one suspects the serving maids and apprentices were more devout readers than the gentry, though perhaps the gentry read them too, late at night, with the candle low and the curtains drawn, their moral outrage conveniently muffled by the rustle of silk sheets. The Calendar itself, in its collected five-volume edition of 1774, sat proudly beside Bunyan’s *Pilgrim’s Progress* and the family Bible on many a humble shelf, three pillars of moral instruction, one of which gleefully detailed how Susan Matthew, age five, met her end at the hands of William York, age ten, on 13 May 1748. York, miraculously, was pardoned, though the Calendar’s author, in a footnote thick with disapproval, remarked that leniency in such cases risked “encouraging the growth of a race of moral dwarfs, stunted in conscience as in years.”

Alongside chapbooks, one might find another oddity of domestic diversion: the *face book*. It wasn’t the digital monolith of the 21st century; it was something far more intimate, and infinitely more ridiculous. A literal book, kept in households, into which guests would attempt to sketch their own portraits during evening entertainment. No mirrors allowed. A crude drawing, a shaky profile, a botched attempt at symmetry, followed by raucous laughter: *“Look at the paucity! Look at the eyebrows, Jeremiah!”* Pages filled with unrecognisable scrawls, caricatures gone horribly awry, the occasional accidental self-portrait that bore more resemblance to a startled badger than the sitter. It was social media, rendered in ink and incompetence, an exercise in vanity, humility, and communal mirth. One imagines Bartholomew Zuckerberg, quill in hand, muttering, *“Bless thee, sir, thy likeness doth resemble a startled turnip.”*

But the *Newgate Calendar*’s evolution continued. Chapbooks gave way to longer, more elaborate narratives, full-length novels dramatising the exploits of thieves, highwaymen, and murderers. These became known as *Newgate novels*, and they walked a fine line between moral instruction and moral corruption. Ostensibly, they warned against vice, but their real appeal lay in vicarious thrill. The reader wasn’t being cautioned so much as invited inside the criminal’s mind, allowed to thrill at the daring escape, the clever ruse, the narrow escape (until, inevitably, the scaffold). Among the earliest were Thomas Gaspey’s *Richmond* (1827) and Bulwer-Lytton’s *Paul Clifford* (1830), the latter opening with that immortal meteorological flourish, *“It was a dark and stormy night,”* a line so famously absurd it became, by ironic fate, the very emblem of overwrought criminal romance. Yet Clifford, like so many of his fictional peers, was no mere villain; he was dashing, intelligent, wronged by society, “a man of honour among thieves,” as the subtitle helpfully clarified, thus ensuring the reader’s sympathy slipped its leash and followed him into the shadows.

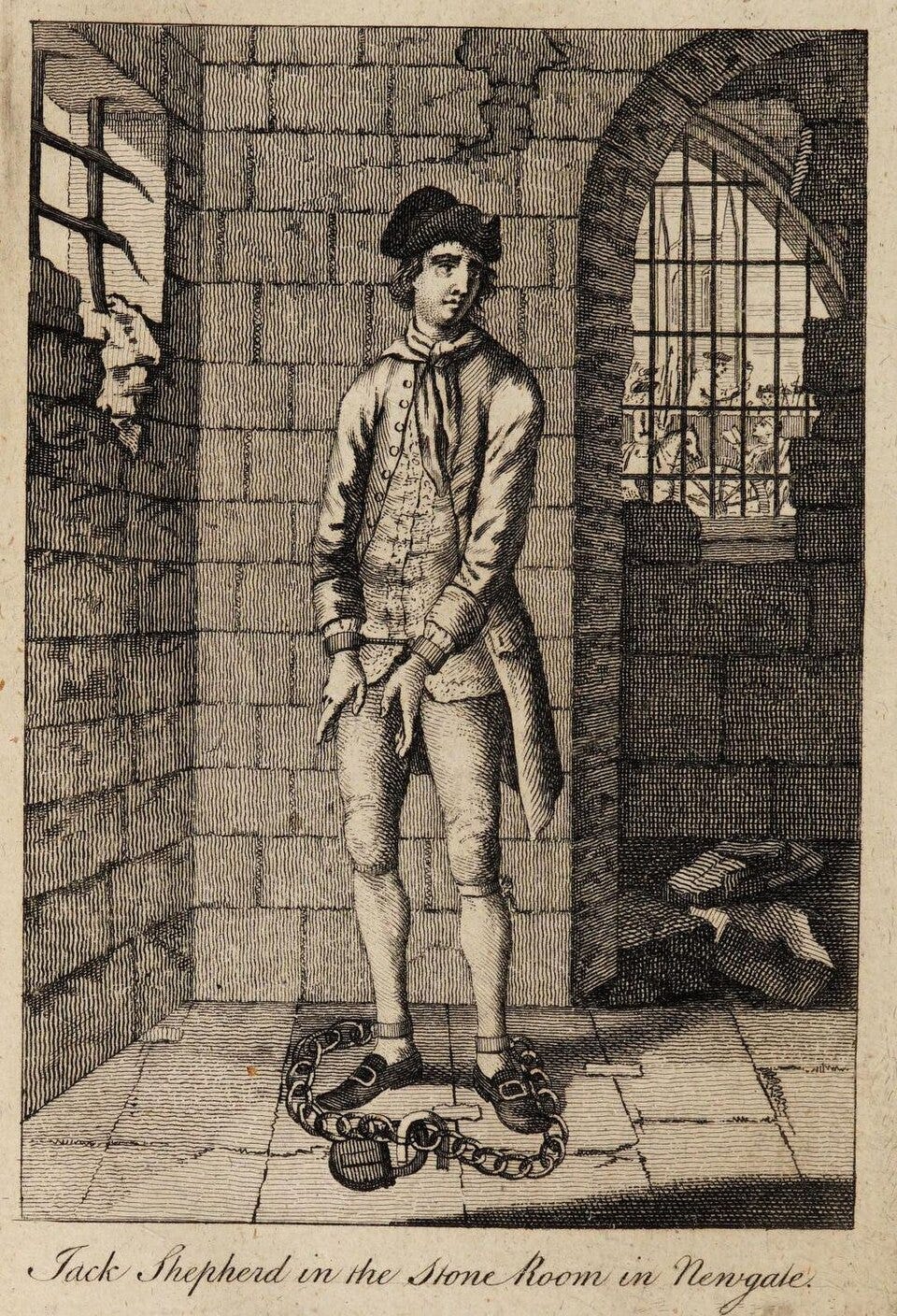

One figure stood at the centre of this controversy: Jack Sheppard. A real person, yes, but elevated to myth by narrative. A thief, a jailbreaker, a man whose two-year criminal career ended at Tyburn, but whose legend lived far longer in print and on stage. William Harrison Ainsworth’s *Jack Sheppard* (1839) did more than recount history; it staged it, inflamed it, gilded it. The novel’s success was so immediate and immense that dramatisations followed within months, plays so feverishly attended that, as Thackeray grimly reported, vendors sold *Jack Sheppard bags* in the theatre lobbies: leather satchels not of commemorative trinkets, but of burglary tools, skeleton keys, jemmies, dark-lanterns, and lengths of cord suitable for descent from upper-storey windows. One or two young gentlemen later confessed, under magistrate’s interrogation, that they owed their first forays into housebreaking not to poverty or desperation, but to the seductive logic of the stage, where every lock yielded with a turn and every constable arrived three beats too late.

It was a world in which objects carried double meanings. Consider the thumb stick, a common walking aid for countrymen, characterised by a U-shaped crook at the top, over which the thumb rested. Innocuous, until one learned its darker utility. The thumb, placed just so, concealed a drilled cavity. Into this cavity, a hook could be screwed, attached to a length of string, ending in another hook. Dangle it through a window, snag a watch or a purse, reel it in. Walk away, thumb still resting nonchalantly on the crook. No suspicion. Until, inevitably, the authorities caught on, and thumb sticks were outlawed outright as instruments of crime. A tool for hiking became a tool for thieving, and the law responded accordingly, adding it to the ever-growing list of proscribed devices that included spring-loaded shoe-knives, collapsible garrottes, and “ladies’ reticules with false bottoms deeper than morality permits.”

The Newgate novel attracted fierce criticism. William Makepeace Thackeray, author of Vanity Fair, despised them for more than their glorification of crime; it was their hypocrisy that truly offended him. They pretended to moralise while luxuriating in transgression. He watched, aghast, as the public turned Jack Sheppard from cautionary tale into folk hero. The gallows didn’t deter; it crowned. His satire *Catherine* (1839), based on the case of Catherine Hayes, who not only conspired to murder her husband but saw to his dismemberment before her own execution by burning at the stake in 1726, was meant as a corrective. But irony, like arsenic, loses potency if dosed too subtly; many readers failed to detect the poison in the punch and took *Catherine* as yet another thrilling descent into vice. Thackeray’s fury reached its zenith after the 1840 murder of Lord William Russell by his valet, François Benjamin Courvoisier, a crime the press linked, sensationally and perhaps inaccurately, to a performance of Jack Sheppard. Though Courvoisier later denied the influence, the damage was done. The Lord Chamberlain banned all stage adaptations of Sheppard’s life. The controversy solidified Thackeray's public stance. He had already attacked Dickens's romanticism in earlier critiques, sneering that Miss Nancy was "the most unreal fantastical personage possible." His scathing essay on attending Courvoisier's execution, On Going to See a Man Hanged, focused on the public spectacle of the gallows, but its unspoken target was the very genre of criminal romance that he believed had helped lead to the scaffold in the first place.

Not everyone abandoned the form. Charles Dickens, for one, persisted, some might say thrived, within its orbit. There’s a strong argument that *Oliver Twist* is, at its core, a Newgate novel. It features Fagin’s den of child thieves, the menacing charisma of Bill Sikes, the doomed allure of Nancy. True, Dickens layers it with social critique, but the engine of the plot remains crime, detection, and punishment. The novel doesn’t just describe a criminal underworld; it invites the reader to navigate it, to feel its rhythms, its dangers, its strange codes. He was, as one contemporary put it, “made of sterner stuff”, or, more cynically, made of more commercially lucrative stuff. He understood what sold: suspense, sympathy for the rogue, the thrill of the chase. And though he took pains to deny it, the spectre of Ikey Solomon, the real-life fence whose trial in 1830 had gripped London, hovered over Fagin; Dickens, ever the master of plausible deniability, neither confirmed nor denied the connection, letting rumour do the work of publicity.

And he wrote accordingly. His famously expansive prose loops and doubles back, lingering on minor details and piling clause upon clause, an effect driven as much by structural necessity as by artistic impulse. He was paid by the installment, not strictly by the word, though the difference was academic; the effect was the same. A sentence like *“which, having not undergone any intermediate process of change”* isn’t just stylistic flourish; it’s economic strategy, a bulwark against the razor of the editor’s pen. Five hundred words delivered, fifty pounds collected. The butler isn’t summoned to fetch tea, he’s summoned to confirm the word count, his silver salver carrying contractual obligations rather than Darjeeling.

The Newgate novel, in time, mutated. Sensation fiction absorbed its tropes, the hidden past, the stolen identity, the shocking revelation. Wilkie Collins’s *The Woman in White* (1859) may lack a highwayman, but its conspiracies, forged documents, and lunatic asylums owe much to the Calendar’s legacy. Detective fiction borrowed its scaffolding, the investigation, the pursuit, the final unmasking, with Collins’s *The Moonstone* (1868) often hailed as the first true English detective novel, a direct descendant of those earlier tales where guilt was less deduced than dramatically unveiled beneath a trapdoor of coincidence. And then came the *penny dreadfuls*: weekly instalments, cheaply printed on wood-pulp paper so thin one could read the next page’s villain peering through the current one’s monologue, feverishly consumed by boys who pooled pennies in reading clubs or rented collected volumes by the hour. They went by other names too, *penny awfulls*, *penny horribles*, *penny bloods*. The term *penny blood* was reserved, according to some bibliographers, for the grimmer fare aimed at working-class adults, stories thick with arterial spray and moral decay, while *dreadfuls* catered to younger appetites: escapades of Sexton Blake, Jack Harkaway, or *Varney the Vampire*, the latter introducing the modern vampire’s sharpened teeth in 1845, a full half-century before Nosferatu bared his fangs.

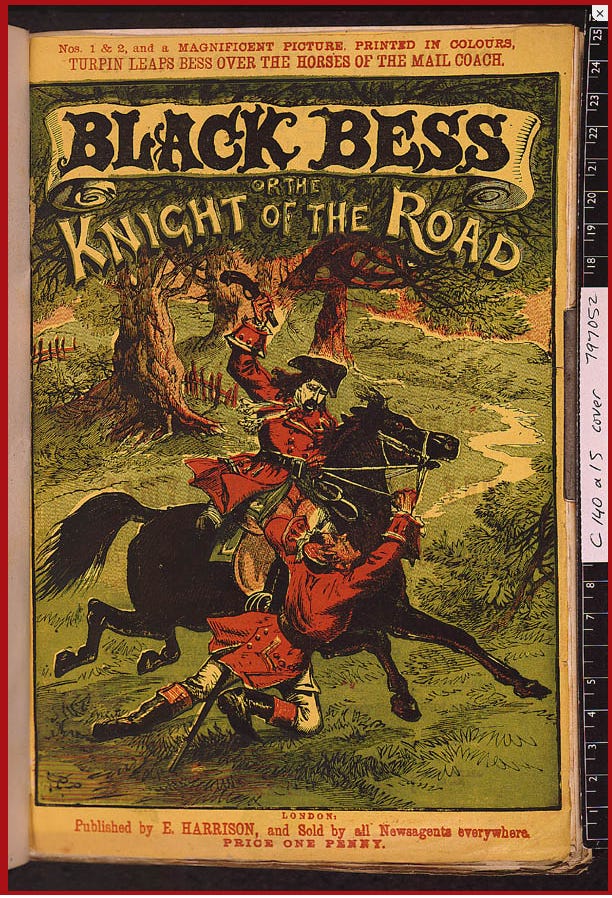

These weren’t shelved alongside Austen or Trollope. They were hidden under mattresses, traded in schoolyards, read surreptitiously by candle stubs. They were also known as penny numbers, a term reflecting their serialised format, issued in weekly or biweekly parts, each a self-contained cliff-hanger designed to ensure the next purchase. *“Next week: The Secret of the Iron Coffin!”* promised the cover of *Black Bess; or, The Knight of the Road*, a 254-episode glorification of Dick Turpin in which the highwayman wasn’t hanged until page 2,207, a feat of narrative procrastination rivalled only by the actual delays of 18th-century justice. Vendors called them out in the streets: “Latest dreadful! Murder in Whitechapel! Escape from Newgate!” Among the alternative titles floated by publishers were *naughty novels*, *filthy newsbooks*, and *dirty foldabouts*, though the official catalogues preferred the vaguer *penny something*, letting the reader’s imagination do the work. *Thou-shalt-nots* appeared as a euphemistic label in certain temperance pamphlets, while street hawkers used *“Don’t look in there, mother’s”* as a sly pitch, winking as they passed a volume to a youth whose mother was, conveniently, out of earshot.

The content varied, some focused on highwaymen, others on poisoners, resurrection men, or fallen women, but the formula held: an opening crime, a series of narrow escapes, a descent into moral ambiguity, and, finally, retribution (though not always swift, and rarely satisfying). These weren’t meant to be kept. They were read, passed on, left behind on omnibuses or in lodging-house drawers, their pages softening at the edges, ink blurring where fingers had lingered too long on a particularly grisly illustration. One publisher’s rallying cry to his engravers, *“more blood, much more blood!”*, captures the spirit perfectly.

The illustrator’s task went well beyond decoration; it was narrative propulsion. Each frontispiece acted as bait, its lurid detail promising escalation: “You see’s an engraving of a man hung up, burning over a fire, and some [would] go mad if they couldn’t learn… all about him.”” These images, often crudely woodcut yet theatrically precise, one might count the rivets on Turpin’s stirrups or the beads of sweat on a resurrection man’s brow, anchored the text in visceral immediacy. Boys pooled pennies in reading clubs, sharing weekly parts until the whole saga was committed to memory; others rented collected fascicles by the hour from street-corner lenders whose inventory hung from hooks like cuts of meat. Edward Lloyd, ever the opportunist, cannibalised Dickens’s success with shameless pastiches, Oliver Twiss, Nickelas Nicklebery, lifting plots wholesale while swapping names and dialling up the villainy. Meanwhile, The String of Pearls (1846–47), anonymous but likely the work of James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, birthed Sweeney Todd: a figure not yet mythic but already monstrous, his bakehouse furnace fed by coal and the unclaimed dead alike. Varney the Vampire, serialized over two years, introduced sharpened teeth as a vampiric hallmark, a detail so potent it outlived the flimsy pulp that bore it. Spring-heeled Jack, though never conclusively real, thrived in the gap between rumour and report: clawed, fiery-eyed, bounding over rooftops in a blur of blue flame and moral panic. His last alleged sighting in Liverpool in 1904 proved the genre’s afterlife: long after the penny dreadful had yielded to the halfpenny marvel, the dread lingered, embedded in alleyway whispers and the flinch at a sudden shadow.

They were the guilty pleasure of the Victorian age, a world away from coffee-house diversions involving glass partitions, flaps, and furious strumpets charging a pound a minute for conversation. (One imagines the strumpets, after hours, forming a prog-rock band: *The Furious Strumpets*, debuting their new track, *Behind the Flap*, complete with theremin solo and a spoken-word epilogue drawn verbatim from the *Newgate Calendar*’s entry on Mary Blandy, who poisoned her father with arsenic slipped into his gruel: *“She said she meant no harm, only to make him love her better.”*)

In France, meanwhile, the cultural exchange took a different turn. Inspired perhaps by British penal drama, or simply by their own culinary ingenuity, they discovered dual uses for the baguette. Day one: food. Day two: weapon. A loaf, once stale, became a truncheon. *For eatin’ and beatin’!* The French, ever practical, noted with resignation that their bread lasted no more than an hour before degradation set in. *“Elle est perdue,”* one might lament, holding a soft, doughy disappointment. The only solution? A boulangerie with a dedicated extrusion slot, direct to mouth, hot and fresh. No packaging. No delay. Just pure, unmediated baguette. (One wonders if Courvoisier, in his final hours, regretted not having armed himself with a *baguette dur* instead of a carving knife. It would have been less effective, but vastly more Gallic.)

Back in England, criminal innovation kept pace. Tartar sauce rustling, yes, that was a thing. Instead of jars clinking in stolen crates, there were whole barrels rolled furtively down cobbled alleys by moonlight, their contents destined for the tables of taverns too thrifty to pay full tariff. The constable, suspicious, produces a slice of toast. *“If this is water, my toast shall be ruined. But if it is tartar sauce…”* He dips. Tastes. Smiles grimly. *“Delicious though this is, I am taking you in.”* Meanwhile, in the shadows of St. Giles, resurrection men debated the tensile strength of grave-ropes, while counterfeiters experimented with starch-based watermark simulacra, each profession refining its craft with the solemn dedication of a cathedral architect.

The Newgate novel faded, but its DNA persisted, in the penny dreadful, in the detective serial, in the tabloid crime story that still leads the six o’clock news. It understood something fundamental: people don’t just want morality tales. They want to peer behind the flap. They want the burglary kit in the bag. They want the thumb stick with the hidden hook. They wanted Jack Sheppard precisely because he was alive, vivid, defiant, until the rope silenced him. And in the silence after, the story kept talking, on the scaffold steps, in the chapbook stall, in the halfpenny Marvel, in the flickering frames of early cinema, where Turpin’s ride to York was reenacted endlessly, horse galloping, cloak flapping, justice always just out of frame.

Thomas Carlyle, ever the dyspeptic sage, once called author biographies *“except the Newgate Calendar, the most sickening chapter in the history of man.”* High praise, one suspects, from a man who knew a good horror when he saw one. For the Calendar, in all its incarnations, ledger, chapbook, novel, dreadful, was never truly about crime. It was about *consequence*. Divine retribution and legal justice both give way to something colder and more precise: narrative inevitability, the fall that gives meaning to the rise, the rope that justifies the leap. And as long as readers lean closer, turning the page despite, or perhaps because of, the illustration of the hanging, the Newgate novel endures. It remains less a relic than a rhythm: the beat of the crowd gathering, the creak of the cartwheel, the rustle of a fresh penny number hot off the press, smelling of ink, ambition, and the faint, metallic tang of blood, much more blood.

Comments

Post a Comment